By: Olaf C. Jensen 1, M. Luisa Canals2 Authors` affiliations:

1Center for Maritime Health and Safety, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark 3Instituto Social de la Marina, Sociedad Española de Medicina Marítima, Tarragona, Spain

Correspondence:

Olaf Jensen, 1Center for Maritime Health and Safety, University of Southern Denmark, Niels Bohrs Vej 9, 6700 Esbjerg, Denmark

E-Mail OCJ@FMM.SDU.dk

Telephone: +45 61513322

Fax: + 45 79 18 22 94

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Seafaring is a global industry and the seafarers have their secondary home and living on board for several months. Self-rated health and some main characteristics of working conditions for the seafarers are described.

Methods:

A questionnaire study regarding the latest tour of duty was carried out among 6461 seafarers in 11 countries.

Results:

The self-rated health in general was good and significantly lower by higher age. The seafarers from the east had longer tours at sea, lower proportions of officers and of older seafarers than the western seafarers´. They work mainly all days a week and on average 67-70 hours per week during periods of 2.5 to 8.5 months at sea. Conclusions:

Working conditions in general differ markedly among seafarers from different nationalities. Self-rated health was assessed as good and did not reflect the working conditions in general. More studies are needed to describe more closely the influence on health and the social life among seafarers.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Seafarers have their secondary home on board during their tours of duty for several months and their health and living conditions are influenced by the working conditions in a global industry, still increasing in size and importance; the world merchant fleet comprises about 1.4 million seafarers of which 2/3 work within multi ethnic crews. The crew composition reproduces the global economic order: none of the seafarers from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) are employed under seafarers from other nations 1. Thirty countries have signed the Convention on the OECD. Member countries in this study are: Denmark, Poland, Spain, United Kingdom. Seafaring has been recognized as a high-risk occupation and the safety and health aspects of work on board ships are a major concern for ship owners and

seafarers 2. The increasing needs for effective and fast transport of goods implicate a continuous change of technology and work organisation on board with new exposures related to health and safety.

While merchant seafaring is a highly international industry, the epidemiological studies of safety and occupational health in seafaring have so far mainly been concerned with national studies. The relevance of international studies has been pointed out for many years 3;4. Studies of the health related aspects of seafaring have mainly been concerned with studies of mortality and morbidity, while studies related to the health of the seafarers are sparse. Self-rated health may be as relevant as or even more relevant to the goals of the health programs for the populations than mortality rates 5. Self-rated health is widely recognised as an excellent predictor for the actual health status and a good predictor for the prognosis of health 6;7.

The objective of the study is to describe the self-rated health and the main characteristics of the seafarers´ working conditions in an international setting.

METHOD

The study was part of a large collaborative project: International Surveillance of Seafarers´ Health and Working Environment 8. A questionnaire study was carried out in 2001 in 11 countries. Two hundred to seventeen hundred questionnaires were collected in each country in one or more medical clinics (31 clinics in all).

The questionnaire, originally written in Danish, was translated into English, Polish, Croatian, Russian, Spanish and Chinese. The English edition was later re-translated into Danish by an independent translator and no discrepancies between the two editions were found. Furthermore, the questionnaires used in Spain, Russia, Ukraine and China were checked and compared to the Danish edition by language specialists, and no significant discrepancies were reported. The questions used in this study were: self-rated health, ship type, flag state, tonnage, main work area, occupational position and, length of the tours and working hours. A short questionnaire without the questions on hours of work and length of the tours was used in Croatia, so the analysis of these two parameters could not be done.

The question used about self-rated health status was adopted from the WHO recommendations for health interviews surveys (from the SF-36)6: How is your healthin general? Five categories were available: Very good, good, fair, bad and very bad. In the analysis “very good” and “good” and “fair” and “bad” were combined, yielding a variable with two categories: “good” and “fair”.

All seafarers, irrespective of age, who have been employed at sea at least on one tour of duty, were eligible to take part in the study. Seafarers employed on factory fishing vessels and employees on supply ships, ferryboats, and pilot boats were included in the study. Fishermen and employees on offshore installations or oil-drilling platform were not included.

A total of 6896 seafarers in 11 countries were asked to participate; of these 6461 agreed to participate, giving a response rate of 94 %.

The seafarers who came to get their mandatory health examinations were asked to fill in a short questionnaire while waiting for their examination, or as an exception after their examination. Anonymity was guaranteed by delivering the completed questionnaires in a closed box before the health check. For registration of non- responders, those who refused to participate were asked to place the blank questionnaire in the same box as those who participated.

Data were processed using SPSS 11.0 and Stata 7.0. Standard errors were used for calculation of the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for means and proportions. Odds ratios and 95% CI from multiple logistic regression analyses were calculated in Stata7.0. The method of multiple logistic regressions was used to assess the relationbetween the two categories of self-rated health statuses on percentages of the other variables. In order to choose the variables for the multiple logistic regression analysis, we used the chi-square test as the basis for choosing the variables in the regression. Variables with p values <0.10 (2-tailed) were included as co-variables in the multivariate analyses. Age and gender was adjusted for: ship type, position on board, length of tours, work area on the ship and nationality. Unanswered or wrongly ticked off questions were always analysed as missing values. To obtain comparability between nationalities means and proportions were calculated specifically for cargo ships and tankers. The lengths of the tours on the latest tour of duty in months were based on the number of days at sea divided by 30, 4. Due to some few outliers, the tour lengths were limited to 14 months in the analyses. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the protocol complied with the medical research ethics.

RESULTS

A total of 6896 eligible seafarers were asked to participate and 6461 participated with a response rate of 94 %. Of the participants in the study, 95 % were from the country of the data collection and 235 (3.6 %) were from foreign nations. The most frequent types of ships were containers, bulk carriers, dry cargo ships and passenger ships. Female seafarers represented nearly 4 % of the population and they worked mainly on passenger ferries. Eighteen percent of the female seafarers and 43 % of the male seafarers were officers.

Table I shows the results of the multivariate analyses for self-rated health with clear differences among the nationalities. Multivariate analysis of self rated health by age groups among seafarers from all types of ships. The adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for good or very good health compared with fair or bad health, in specific age-groups compared with the totals were: Age goups: 16-29 OR=1.41(95% CI:0.80-2.48), 30-39: OR=0.76 (95% CI:0.47-1,23), 40-49:OR=0,57(95% CI:0.35-0.93), 50+:OR=0,47 (95% CI:0.29-0.78). The adjusted odds ratio forfemales compared to males with “good” health was 2.65 (95 % CI: 0.34-19.4). When the category “very good health” alone, was compared to the other possible categories of health, the adjusted odds ratio for female seafarers = 2.04 (95 % CI: 1.15-3.60).

The adjusted odds ratio for good self-rated health for those who worked 7 days and more than 80 hours per week and more than 92 days at sea compared with all others, was 0.90 (95 %CI: 0.76-1.07).

None of the multivariate analyses for self-rated health were significantly different forthe following variables: officer/non-officer), length of the tour at sea </> 90 days), working area (deck/machine, service) and type of ship (cargo ship, passenger ship, tank ship or other types of ships).

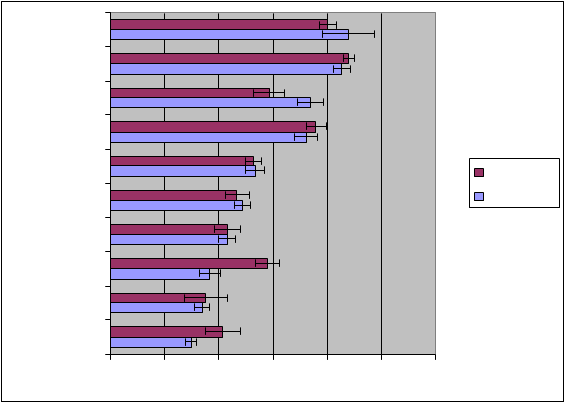

The length of tours at sea varied markedly among the nationalities (Figure 1). The mean number of working hours per week on cargo ships was 68 hours for non-officers and 69 hours for officers. Eighty-one % of all seafarers worked seven days a week and one third worked more than 11 hours a day, seven days a week. Eighteen percent had 70 working hours per week, 25 % worked 84 hours per week (seven days with 10 and 12 hours a day, respectively) and 5 % worked more than 90 hours per week.

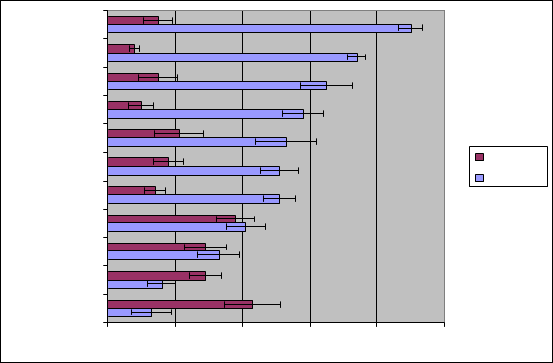

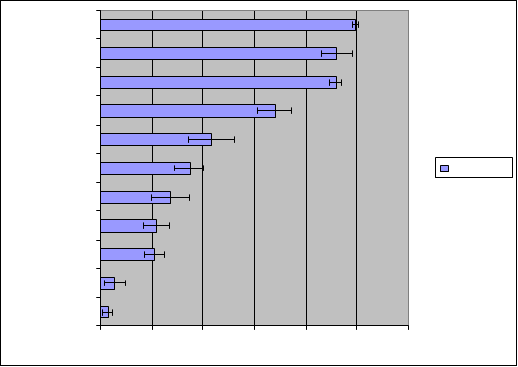

The proportions of non-officers were highest in the eastern countries (Figure 2). The proportions of seafarers who worked on ships from foreign flag were also mainly from the eastern countries (Figure 3). In contrast to this the number of older seafarers over 50 years was predominantly in the western nationalities (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The question for self-rated health (General Health) is one of several indicators of the quality of life, included in the SF-36 standardised questionnaire 9. Separate use of the question about the general health status from the SF-36 questionnaire has been widely used 5. In a study of the general population in Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania, 90 %, 92 %, 88 % and 93 % respectively reported their health either as “good” or “reasonably good”10. The seafarers were expected to be at least as healthy as or healthier than the general population due to the minimum health conditions required passing the regular health examinations. Assuming that the questions are comparable, the percentage of 93 % of the seafarers with very good - or good health, was on the same level or higher than the general population in the four countries.

Expressing a low self-rated health at the health examination might not be beneficial for the seafarers in order to keep the job and the results therefore are supposed to be biased towards better condition. To minimise this bias, full anonymity was guaranteed, but we cannot exclude all fear or threat that the answer might be used in a negative way for the seafarers. Though cultural comparisons of self-rated health should be made with caution11, we cannot exclude that the significant differences of the self- rated health among seafarers from different parts of the world (Table I) may in part reflect true differences.

Negative impact of the long hiring periods for seafarers and their family life has been described and it has been recommended to have shorter trips, continuous employment and opportunities for partners and family to sail 12. In this study, seafarers from some of the countries with very long tours of duty had a higher self-rated health, than for seafarers with shorter tours of duty. (Table I and Figure 1). This indicates that the length of the tours as a single determinant is not a strong predictor of the self-rated health. Female seafarers hada higher self-rated health and this may be explained partially that they are mainly employed in catering on short term employment. Further explanations remain to be studied.

The majority of the seafarers worked seven days a week. Seafarers who work every day of the week have less time to relax from work to do leisure activities including time to do physical training and to keep the contact to the family at home. In a study of the family relations for the Philippine seafarers, Lamvik concluded that the Philippine seafarers through their work at sea offered sacrifices to the families at home as migrant workers 13. This may be one of the explanations why long tours of duty combined with many work hours per week do not have a negative impact on self-rated health. Corresponding to other studies, higher age was significantly correlated with a lower self-rated health 14.

The proportion of seafarers of more than 50 years of age was low for seafarers from some of the eastern countries and (Figure 2). As one possible explanation it has been noted that some hiring agencies in the Philippines primarily want to hire the youngest seafarers 15. A selection out of the occupation by higher age can have social medical impact for the seafarer and his/her family who is dependent of the income which remains to be studied further.

CONCLUSIONS

The seafarers from the eastern countries mainly work as non-officers on foreign flag state ships during longer tours at sea tours at sea. National differences in the general working conditions do not reflect any differences in the self-rated health. There is a need to study more closely the influence on health in relation to the working conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All participating seafarers, maritime doctors and clinics, the maritime research institutions, the governing body of the International Maritime Health Association (IMHA) and all colleagues in the participating countries are thanked for their commitment and help in this project. The International Transport Workers Federation (ITF) Seafarers' Trust (ref. no. 1567) provided vital financial contribution. The project is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The data collection was coordinated by: Dr. Wilfredo J. P. Arguelles in the Philippines, Prof. Michael Bloor in the UK, Dr. Toka H. Pangemanan in Indonesia, Dr. Graham M. Rosendorff in South Africa, Prof. Stanislaw Tomaszunas in Poland, Dr. A.A.Mozer in Arkhangelsk, Russia, Dr. Lilia Zvyagina in Ukraine, Dr. M. Luisa Canals, in Spain, Dr. Yunping Hu, Shanghai, China and Dr. Nebojsa Nikolic, Croatia. Mr. Jens FL Sørensen is thanked for his assistance with project development, coordination, data-collection and data-analysis. Dr med. Anthony Low, Hamburg gave linquistic support.

REFERENCES

1 Lane T, Obando-Rojas B, Sorensen M, Wu B, Tasiran A. Crewing the International Merchant Fleet. 2002. Surrey, Lloyd's Register - Fairplay Ltd. 5-1-2002.

2 ILO. Accident prevention on board ship at sea and in port. 2 ed. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 1996.

3 Goethe H, Vuksanovic P. Distribution of Diagnoses, Diseases, Unfitness for Duty and Accidents Among Seamen and Fishermen. Bull Inst Marit Trop Med Gdynia 1975; 26(2):133-151.

4 Schilling RSF. Section of Occupational Medicine. Proc R Soc Med 1966; 59:405- 410.

5 Rohrer JE. Medical care usage and self-rated mental health. BMC Public Health 2004; 4(1):3.

6 WHO. Health Interview Surveys. Towards international harmonization of methods and instruments. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996.

7 Heistaro S, Jousilahti P, Lahelma E, Vartiainen E, Puska P. Self rated health and mortality: a long term prospective study in eastern Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001; 55(4):227-232.

8 Jensen OC, Laursen FV, Sørensen JFL. International Surveillance of Seafarers' Health and Working Environment. A Pilot Study of the Method. Preliminary Report. Internat Marit Health 2001; 52(1-4):59-67.

9 Ware JE. SF-36® Health Survey Update. 2004. http://www.sf-36.org/. 5-5- 2004.

10 Kasmel A, Helasoja V, Lipand A, Prattala R, Klumbiene J, Pudule I. Association between health behaviour and self-reported health in Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania. Eur J Public Health 2004; 14(1):32-36.

11 Jylha M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Jokela J, Heikkinen E. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998; 53(3):144-152.

12 Thomas M, Sampson H, Zhao M. Finding a balance: companies, seafarers and family life. Marittime Policy & Management 2003; 30(1):59-76.

13 Lamvik GM. The Filipino Seafarer - A Life between Sacrifice and shopping.

Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology; 2002.

14 Nolte E, McKee M. Changing health inequalities in east and west Germany since unification. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58(1):119-136.

15 Knudsen F. "If you are a good leader I am a good follower". Arbejds- og fritidsrelationer mellem danskere og filippinere om bord på danske skibe. 8. 2004. Esbjerg, Forskningsenheden for Maritim Medicin. Arbejds- og Maritimmedicinsk Publikationsserie.

16 Lane T. The Social Order of the Ship in a Globalized Labour Market for Seafarers.

1994. Liverpool, Dept. of Sociology, University of Liverpool.

Table 1

Multivariate analysis of self-rated health among seafarers from all types of ships by nationality and the adjusted odds ratios 1 and 95%confidence intervals (n=6,113).

|

Very good or good 2 |

|||||||

|

Very good |

Good |

Both |

Fair or bad |

Total |

Odds ratio |

95%CI |

|

|

Indonesia |

46 % |

52 % |

98 % |

1 % |

495 |

5,9 |

2,6-13,5 |

|

Philippines |

53 % |

44 % |

97 % |

2 % |

1609 |

3,4 |

2,4-4,9 |

|

UK |

45 % |

51 % |

96 % |

3 % |

569 |

3,1 |

1,8-5,2 |

|

Ukraine |

11 % |

85 % |

96 % |

3 % |

389 |

2,9 |

1,5-5,8 |

|

South Africa |

43 % |

50 % |

93 % |

6 % |

186 |

1,1 |

0,5-2,1 |

|

Denmark |

36 % |

55 % |

91 % |

8 % |

799 |

0,9 |

0,6-1,2 |

|

Russia |

7 % |

83 % |

90 % |

9 % |

338 |

0,8 |

0,5-1,3 |

|

Spain |

16 % |

72 % |

88 % |

12 % |

717 |

0,6 |

0,4-0,8 |

|

Poland |

38 % |

49 % |

87 % |

12 % |

305 |

0,5 |

0,3-0,7 |

|

Croatia |

42 % |

43 % |

85 % |

14 % |

156 |

0,4 |

0,3-9,8 |

|

China |

16 % |

62 % |

78 % |

22 % |

550 |

0,2 |

0,1-0,3 |

|

Total |

35 % |

57 % |

92 % |

7 % |

6113 |

1,0 |

|

- 1 adjusted for age, ship type, position on board, length of tours and work area on the ship

- 2 very good or good compared with fair or bad, each stratum was compared with

the total

Mean length of the latest tour of duty in months and 95% confidence intervals for officers and non-officers on cargo ships (n=3,138).

|

IndonesiaPhilippines China Ukraine Russia Poland Not-officer Officer Spain South Africa UK Denmark |

0,00 2,00 4,00 6,00 8,00 10,00 12,00

Proportions of seafarers over 50 years of age and proportions of ratings (position as non-officers) on cargo ships and 95% confidence intervals. (n=3,586 for age and n=3,533 for position)

|

|

Indonesia Philippines South Africa Ukraine Croatia Russia China Age 50+ Ratings Spain Poland Denmark UK |

0 0,2 0,4 0,6 0,8 1

Figure 3

Proportions of seafarers on cargo ships who worked on foreign nations´ ships by nationality and 95% confidence intervals (n=2,735)

|

|

Poland Indonesia Philippines Ukraine UK |

Spainother flag

South Africa

Russia

China

Croatia

Denmark

0,00 0,20 0,40 0,60 0,80 1,00 1,20

Papers relacionados