Hale, Andrew

Safety Science Group / Delft University of Technology / Postbus 5015 / 2600 GA Delft / Netherlands+31 15 2781706 / a.r.hale@tbm.tudelft.nlYtrehus, IngvildSINTEF / Strindveien 4 / Trondheim N-74654 / Norway+ 47 73 59 30 00 / Ingvild.K.Ytrehus@sintef.no

ABSTRACT

This paper describes the survey set up by the International Social Security Association (ISSA) and taken over by the European Network of Safety & Health Professional Organisations (ENSHPO), which is collecting data on the tasks carried out by safety professionals in a range of European countries. It provides some background of the reasons why the survey was undertaken, describes the set up of the survey, the design of the questionnaire and the way in which it was distributed and analysed. It serves as introductory paper to the session on this topic, which will contain results from a range of countries.

Keywords

Keywords

Safety professional, roles and tasks, international comparison

INTRODUCTION: some history

The safety profession is a venerable one. We can trace its origins back to 1844, when legal requirements were first made for accident prevention measures such as machinery guarding [9]. Inspectors had the powers to declare any part of machinery dangerous, although the employer could only be prosecuted if there was subsequently an accident as a result of that particular part of the machine. Specialist technical inspectors were first appointed in the UK in 1899 and the first national safety museums were established in Germany and the UK from the 1890s onwards [11]. The first ‘safety officers’ employed by industry can be traced to the origins of the “Safety First Movement” during and after the First World War. Their primary tasks were to ensure discipline in following safety rules, using protective equipment and not removing safety fencing (guards). After the Second World War, these safety officers began to get together in a number of countries to form an association. These associations — aided and directed by regulatory initiatives — began on the path of professionalisation of the discipline, leading through the stages of regulating entry requirements, defining training requirements and a career path in the profession, defining the areas of expertise and tasks belonging to the profession, striving to protect that area of professional practice with statutory rules, and stimulating the academic development of the discipline underpinning that area [1, 6, 8, 19].

Throughout this century and a half of history, a broad shift in the area of concentration of these (proto-)safety professionals can be traced. The first “technological age” of safety remained dominant for the professional group until well into the 1980s and is still an important strand in the tasks that safety professionals perform [18]. From the 1920s, a second strand was added, arising from studies of accident proneness, namely the selection and training of workers. After the Second World War, the emphasis was shifted to the design of jobs and man–machine interfaces. From the 1980s, this was overtaken by the “third age of safety” which heralded the dominant concern for safety management [18]. However, it is not clear what the effect of all of these changes has been on the actual jobs being carried out by safety professionals in their companies, inspectorates and consultancies.

THE ACTUAL TASKS OF SAFETY PROFESSIONALS

A number of influences can be postulated which will add up to determine the tasks that safety professionals actually do.

The first influence is the law, in so far as that specifies tasks for identified groups. In European law, based on the 1989 European Framework Directive, a number of countries have required the appointment of safety and health personnel [7]. Most have only defined tasks, without defining which professional group should do them[15]. Norway is an example, where compulsory tasks for health and safety personnel include [10]:

- 1. Assisting with the planning and implementation of the establishment, maintenance and modifications of workplaces, premises, equipment and production methods, and preparing guidelines for the use of chemicals, machines and equipment.

- 2. Assisting with a continuing assessment of the working environment, conducting workplace inspections and assessing the risk of health damage and injuries.

- 3. Promoting suggestions on preventive measures and working actively for measures which remove causes of sickness and accident risks.

- 4. Monitoring and controlling workers’ health with respect to work situation and undertaking the necessary followup.

- 5. Assisting in the adjustment of work to the employee.

- 6. Assisting with the provision of information and training in the areas of workers’ health, occupational hygiene, ergonomics, and general safety and environment work.

- 7. Giving information on health, environment and safety risks to the employer and employees.

- 8. Assisting with internal occupational rehabilitation in companies. Further, the employer must cooperate with health and safety personnel in the preparation of the following documentation:

- 9. Periodical plans for the health and safety personnel’s work in the enterprise, which will be included as a part of the enterprise’s total work plan.

- 10. Periodical reports or annual reports, which include the presentation of risk assessment, risk evaluation, suggestions of preventive measures and results.

- 11. Reports, measuring results, etc, which describe working conditions and health problems.

The tasks defined in the law in any country are usually based on a political debate, which may be informed by evidence of what the professionals actually do, but does not seem to be based on direct scientific studies of it. The professional association is often the source of this information to the political process. As such, this association is a second influence, through the work that it does to codify tasks and training

requirements [26]. The context of these deliberations usually determines that any such publications have a strong political content, claiming territory or taking positions about what should be done.

The employer is a vitally important influence on the work done by the safety professional. The direct employer determines the job description, or as contract principal determines the tasks that the safety consultant has been hired to carry out. The vision that employers have of the objectives of their own safety policy and the expertise that they need to realise it will determine what the emphasis is. Companies and industry associations sometimes write up these task specifications, but not usually in the easily available literature.

Finally, the development stage of the science and technology of safety and safety management also determines what knowledge is at the disposal of safety professionals, and hence the tasks that they can sell themselves on and carry out.

However, when we look at the literature on the role and tasks of the safety professional, it is striking that the vast majority of papers and reports are largely normative in character. They tell us about what various players in the system think the job should be, or even what they believe it is [2, 4, 14, 20]. Hardly any studies are available in the literature about what the safety professional’s job actually entails. A few studies in the United States indicate that there is great variability in the tasks performed by safety professionals depending on the hazards in the specific operations, the size and nature of the company, and its management and structure [22, 23, 24]. DeJoy tried to cluster the jobs that were actually being done into dimensions [5]. He identified five (and found little difference in the content of these over different industries):

- 1. Serving as a safety consultant/advisor;

- 2. Coordinating compliance/control activities;

- 3. Assessing the effectiveness of controls;

- 4. Analysing hazards and losses; and

- 5. Conducting specialised studies and reviews. Both DeJoy’s study [5] and other work [3, 17, 23] have emphasised the importance of the communication, consultation and change agent roles of the safety professional. Brun and Loiselle carried out a study of the current situation in Quebec concerning the roles, functions and activities of safety practitioners [3]. Three activity profiles for safety professionals were identified:

- 1. The organisational/strategic profile, which focuses on developing prevention programs, compiling accident statistics, setting up an OHS management system, and organising meetings of the OHS joint committee. It is work primarily at a strategic level, concerning the safety management system and closely linked to the company’s business decisions;

- 2. The organisational/operational profile, which is characterised by more operational activities, such as investigating work accidents, controlling the financial aspects of accident insurance, and bringing together legal information; and

- 3. The technical/operational profile, which focuses primarily on the technical dimension at the operational level. A large part of this safety professional’s time is devoted to choosing individual and collective protection equipment, providing company management with technical advice, and monitoring such things as lockout procedures.

A study in the Netherlands [17] concentrated particularly on the overlap and collaboration with occupational hygienists and, to a lesser extent, with the other professionals required by Dutch law to collaborate in the working conditions services. Three clusters seem to emerge: one around the safety professional, with strong links

to occupational hygiene and ergonomics and to a lesser extent to fire; one around the medical personnel; and one around the organisational specialists (work & organisation psychologists), with the link from them to the medical and ergonomic areas being defined by the attention for stress and absence.

This overlap of tasks indicates that the area of health and safety, or risk control, is a crowded professional area, with a number of different professional groups working in it. This can lead to fruitful collaboration, but often it does not [21]. It certainly leads to rivalry between the professional groups and to confusion among those who employ them [2, 17, 26].

AN INTERNATIONAL STUDY OF SAFETY PROFESSIONALS’ TASKS

The above network of questions and practical and political factors led to the decision in 2000 (initially within the ISSA working group on the training of health and safety professionals, but later transferred to ENSHPO) to set up a survey of the actual tasks being done by safety professionals in the different member countries. The ISSA working group had conducted a number of surveys in the two decades of its existence. These had collected comparative data, largely across European countries, about the law relating to professional competence in health and safety, the training programmes conducted in different countries to provide that competence, and the certification and accreditation systems for assessing and approving both the courses and the competence of their graduates. These surveys had originally been conducted for the range of health and safety professionals, particularly concentrating on the core disciplines of safety, occupational hygiene and occupational medicine, with some attention to occupational health nurses and ergonomists [4, 14, 15, 26]. In the last decade of its existence the working group concentrated its efforts mainly upon the safety practitioner, as this group had no international body addressing its activities in the way that the IEA does for ergonomists, IOHA for the hygienists and ICOH for the occupational physicians. However, all of these studies were largely normative in nature, describing what the law required of safety professionals and what they were trained for, but not what they actually did. The working group, therefore identified the following objectives for the current study:

- 1. To investigate the gap between the regulations and the actual work in practice done by safety practitioners;

- 2. To compare the work of safety professionals across countries to see whether the level and range of tasks that they carry out is comparable. This has an effect on mutual recognition of qualifications and for deciding which training experiences are transferable from one country to another;

- 3. To investigate whether there are different profiles within the safety profession, within or between countries, which need to be linked to different training requirements; and

- 4. To form a stronger basis for deriving learning objectives for the courses in each country and, eventually (if the study could be extended to the work of other professional groups), to group course members from different professions together for training on the basis of similarities in the competence that they require.

Scope of the study

The preparatory group, consisting of experts from Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Switzerland, decided to limit the scope of the study to safety professionals in industry and not to include inspectors. In some countries (notably, in north-western Europe), there is a considerable interchange of personnel between inspectorates and industry or consultancies, and those destined for each type of job will often attend the same training course. Hence, people on both sides consider themselves as members of the

same profession. In the rest of Europe, there is a much greater chasm between these jobs, which do not share the same training or background of those who do the work. To avoid respondents in the latter countries being alienated by having to read through a range of inspectorate tasks, which would be totally irrelevant to them and to shorten the questionnaire, we decided not to send the questionnaire to inspectors and to restrict the section on enforcement and regulatory activities considerably.

The geographical scope of the study was set primarily to Europe, but it was agreed that any country could in principle take part. Approaches were made to all EU and European Economic Area members and to as many candidate countries as possible, where information was available about professional safety associations.

The following countries are in the process of conducting the survey: the Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Britain, Austria, Switzerland, Cyprus, Germany, Poland, Finland, Australia and Portugal. The following countries have indicated their agreement and we are hoping they will take part: Sweden, Denmark, Spain, Ireland, France, and Belgium. There has been a preliminary agreement to participate from the following candidate countries, but problems of financing and organisation still have to be overcome: Estonia, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire (see appendix to this paper and http://www.enshpo.org, where the questionnaire is downloadable) was based on the available literature about safety professionals’ tasks and on the results of previous ISSA studies. The tasks of the safety professionals were divided into 8 sections, conceiving of the job as one of assessing risk and identifying problems of risk control and of proposing solutions to those problems. These solutions consist of technical (hardware) design controls, controls depending on human behaviour, guided by procedures, training and motivation or safety culture, and controls at the level of the management system, which involve setting up and running a safety management system, ensuring that performance is assessed and learning from shortcomings takes place [13, 16, 25]. We also wished to include the idea that the control of hazards has to take place through the whole life cycle of the technology, from design through operations to maintenance and taking in the phase of emergencies, which must be planned for and managed. Finally the questionnaire asks about tasks relating to the management of the safety function itself and to the retention and extension of professional competence. It had been the original plan to pose the questions about the assessment of risks and design of controls separately for a wide range of different types of hazard, in order to see whether the safety professionals required a different depth of knowledge about some types of hazard than others. However, this would have made the questionnaire far longer and we were afraid that it would already be too long to get a good response. Hence these two sections of the questionnaire were separated. A few exemplary areas of hazard were picked out for checking of the depth of task carried out, while a separate section was made to enquire which hazards professionals dealt with. In both task and hazard sections the respondents were asked to say how frequently they had dealt with a particular task or hazard. It was felt that this would give a sufficient indication of the depth of knowledge required about them.

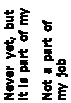

We were also interested in the role of the safety professional as coordinator, liaising between various groups inside and outside the company. A section was therefore included on the frequency with which the respondents had contact with different people, from shop floor to top management and from staff departments to external experts, regulators, inspectors or the public.

Finally we wanted to explore whether there were differences in all of these tasks, hazards and contacts depending on various demographic factors. It seemed interesting to see if those working in different industries had similar tasks, suggesting that the

profession was not limited or split up by industry boundaries. Since many countries distinguished safety consultants, working for many companies, from internal safety advisers, we included questions on this aspect, and on whether they worked for large multi-site or multinational companies or for small or medium-sized companies. We also wanted to find out if there were large differences in the tasks carried out depending on the level of primary education and the level of safety training enjoyed by the respondents, or according to whether he/she worked as part of a team with other health and safety professionals, or just as a lone professional.

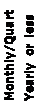

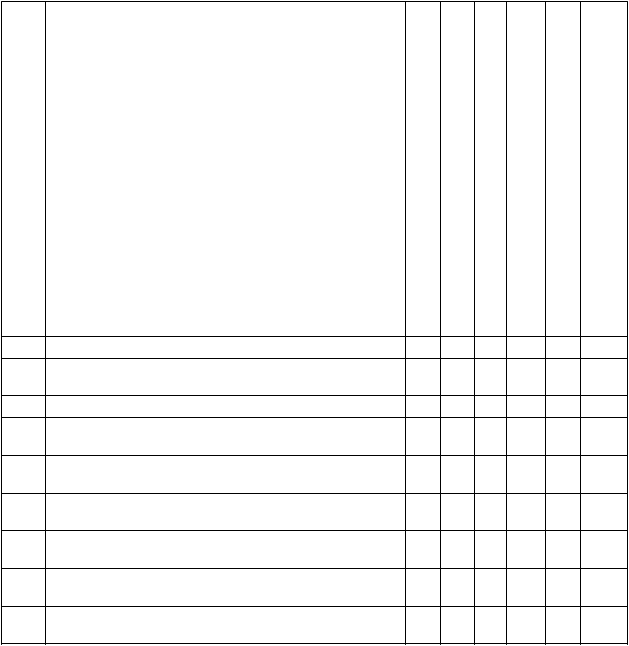

The final version of the questionnaire consists of 173 questions divided into five sections, and takes an estimated 45–60 minutes to complete. This is an indication of the complexity and variety of the safety professional’s possible tasks. The sections are:

A. Information about the organization(s) for which the respondent worked, how many employees the safety tasks cover and in how many sites or countries, and whether other professionals in the area of risk or working conditions worked in the same organization.

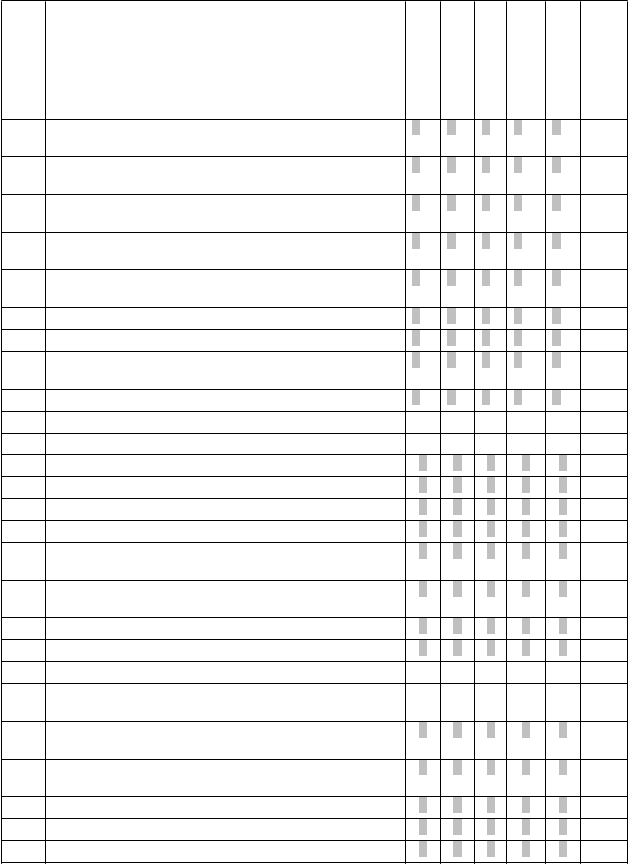

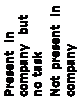

B. A list of 83 tasks, which the respondent has to check according to how often they are conducted (weekly, monthly, yearly, never yet, not part of the task). The list distinguishes tasks relating to: (1) risk identification and analysis; (2) solution development; (3) training, information and communication; (4) inspection and research; (5) emergency procedures; (6) regulatory tasks; (7) knowledge management; and (8) management and financial aspects of the safety function.

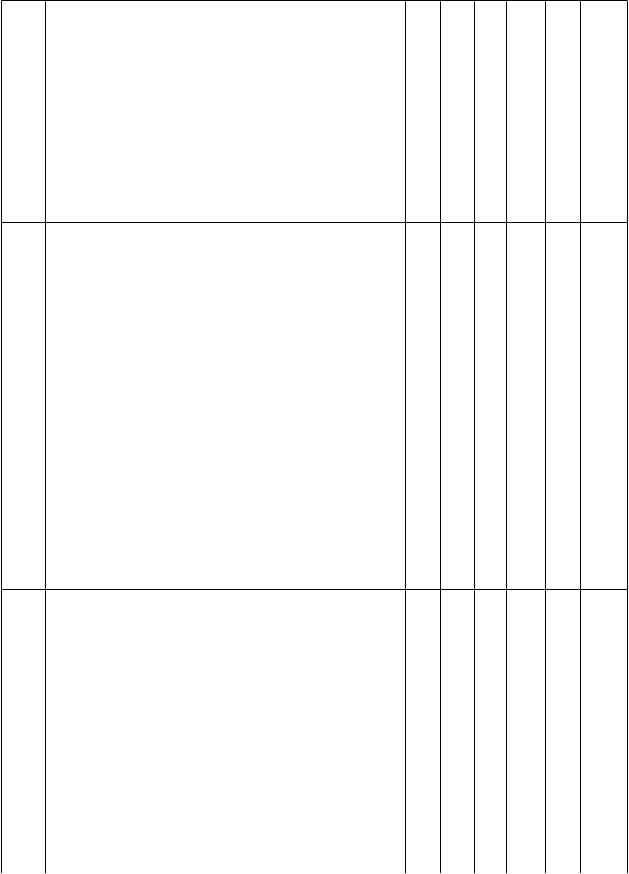

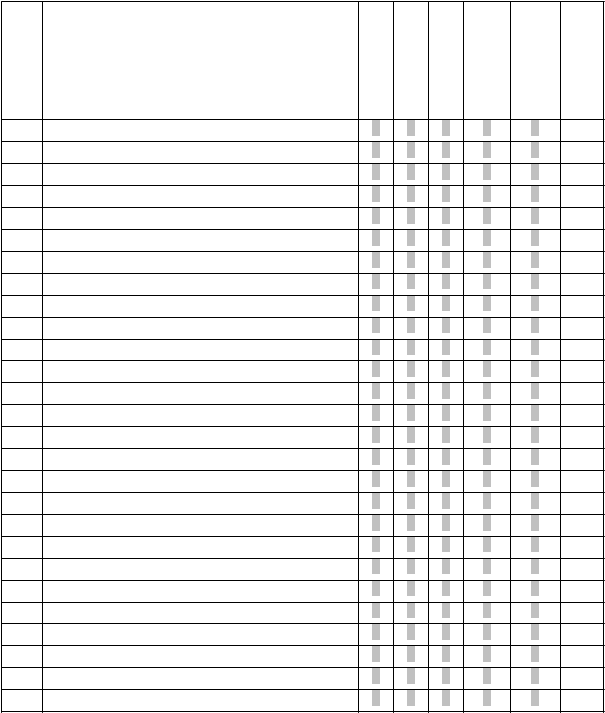

C. A list of 31 types of hazard, which the respondent has to check according to how frequently these are dealt with.

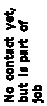

D. A list of 36 types of people, from within and outside the company, with whom the respondents might interact, again with the question as to how often the interaction happens.

E. Personal information about the respondent, including age, gender, length of experience, education, safety qualifications and job title.

The master version of the questionnaire was developed in English, for approval by the ISSA working group. Translations were then made into the necessary different languages for the study. Where possible, this translation process was closely monitored by a member of the preparatory group who was fluent in both languages and back-translations were used as checks. This process gave rise to an enormous amount of discussion about the exact meaning of specific words and was an education in itself. The parallel language versions — which are also available on the ENSHPO website — will be a valuable contribution in their own right to the development of a multilingual thesaurus of health and safety. Versions of the questionnaire are currently available in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Polish, Finnish, Dutch and Norwegian. Versions in Spanish, Swedish and Danish are in production.

A small number of questions had to be tailored to the national situation, notably, the questions asking about educational levels, safety qualifications, professional organisations and specific terms for national bodies and employing organisations. Apart from this, the numbering and formulation of questions have been made strictly uniform, so that data can be compared between countries without an analyst needing to understand the language of each country.

Organisation of the study

Because little or no central financing was available from either ISSA or ENSHPO, it was agreed that each country would need to finance its own study. In order to keep costs low, countries were encouraged to seek the collaboration of the professional association(s) in their country so that questionnaires could be sent out with other mail from that body. They were also encouraged to approach research or education

establishments, which could provide facilities for coding and analysis. The Delft University of Technology, Safety Science Group, provided central advice on the survey and analysis. Funds are being sought for the further analysis which will result if we wish to make detailed comparisons between countries.

The studies in the Netherlands and Norway were conducted first and served as pilots for testing the questionnaire and the analysis methods. The data were collected in 2002 and analysed in 2003, with a preliminary report of the main findings appearing in September 2003 to guide work in other countries.

Other papers at this conference will report the results from a number of individual countries and the first comparisons across countries.

REFERENCES

- 1. Atherley, GRC and Hale, AR. Prerequisites for a profession in occupational safety and hygiene. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 1975, 18: 321334.

- 2. Booth, RT, Hale, AR and Dawson, S. Identifying and registering safety practitioners. Safety Science 1991, 14: 231240.

- 3. Brun, J and Loiselle, C. The roles, functions and activities of safety practitioners: the current situation in Quebec. Safety Science 2002, 40: 519536.

- 4. Cattaruzza, E and Huguet, M. Training of prevention experts: summary report. Paris: International Social Security Association, Section on Education and Training in Prevention, Caisse Regionale d’Assurance Maladie d'Ile de France, 1993.

- 5. DeJoy, D. Development of a work behaviour taxonomy for the safety function in industry. Accident Analysis & Prevention 1993, 25(4): 365374.

- 6. Dingwall, R. Professions and social order in a global society. Paper presented at the International Sociological Association Working Group 02 Conference, Nottingham, 1113 September 1996.

- 7. European Commission. Directive concerning the execution of measures to promote the improvement of the safety and health of workers at their work and other subjects (framework directive). Official Journal of EC, 12 June 1989.

- 8. Evetts, J. The European professional federations: the diffusion of professional expertise Paper presented at the Workshop on the Politics of Regulations, Barcelona, 2930 September 2002.

- 9. Factories Act 1844. GB 1844. Chapters 7 and 8 Victoria, c 15.

- 10. Forskrift om verne og helsepersonale (Regulation on safety and health personnel). FOR 19940421. Norway, 1994.

- 11. Hale, AR. The role of HM inspectors of factories with particular reference to their training. Birmingham, UK: University of Aston, 1978. PhD thesis.

- 12. Hale, AR. The training of professionals in prevention. In the proceedings of the International Social Security Association Conference on Education and Training in Prevention, Caisse Regionale d’Assurance Maladie d’Ile de France, Paris, 1989.

- 13. Hale, AR. Occupational health and safety professionals and management: identity, marriage, servitude or supervision? Safety Science 1995, 20(23): 233246.

- 14. Hale, AR. Why occupational health and safety experts? In the proceedings of the International Symposium of the International Social Security Association: Training of occupational health and safety experts; issues at stake and future prospects, Mainz, 30 June2 July 2000.

- 15. Hale, AR. New qualification profiles for health and safety at work specialists. In the proceedings of the International Social Security Association Conference on Innovation and Safety, Vienna, 2731 May 2002.

- 16. Hale, AR, Heming, B, Carthey, J and Kirwan, B. Modelling of safety management systems. Safety Science 1997, 26(1/2): 121140.

- 17. Hale, AR, Heming, B, Musson, Y and van der Broek, B. De veiligheidskundige professie: kansen en bedreigingen (The safety profession: chances and threats). Utrecht: Nederlandse Vereniging voor Veiligheidskunde, 1997.

- 18. Hale, AR and Hovden, J. Management and culture: the third age of safety. In Feyer, AM and Williamson, A (eds). Occupational injury: risk, prevention and intervention. London: Taylor & Francis, 1998, pp 129166.

- 19. Hale, AR, Piney, M and Alesbury, R. The development of occupational hygiene and the training of health and safety professionals. Annals of Occupational Hygiene 1986, 30(1): 118.

- 20. Hale, AR and Storm, W. Certification of working conditions in the Netherlands: quality assurance or stranglehold? Delft: Delft University Press, 1997.

- 21. Hale, AR and Voets, JL. The collaboration between Arbospecialists in the Netherlands In Bedford, T and van Gelder, PHAJM. Safety and Reliability. 747753. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. 2003

- 22. Kohn, JP et al. Occupational health and safety professionals: who are we? What do we do? Professional Safety, January 1991, pp 2428.

- 23. Limborg, HJ. Qualifying the consultative skills of the occupational health and safety service staff. Safety Science 1995, 20: 247252.

- 24. Minter, S. Safety director’s career outlook: a special report. Occupational Hazards, March 1988, pp 3742.

- 25. Petersen, D. Safety management. New York: Aloray, 1988.

- 26. Storm, W and Hale, AR. Training courses in safety and health: overlaps within and between four European countries. Report to the International Social Security Association. Delft: Safety Science Group, 1995.

- 27. Swuste, P and Arnoldy, F. The safety adviser/manager as agent of organisational change: a new challenge to expert training. Safety Science 2003, 41(1): 1527.

APPENDIX: THE QUESTIONNAIRE

The full text of the master questionnaire as posted on the website of ENSHPO is given below. Any researchers may use it, but we request that you inform us of the results obtained by using it.

Questionnaire Safety Professionals:

What tasks does a safety professional carry out?

Section A Organisation

This section is concerned with establishing what kind of organisation you work for.

Please circle just one of the shaded numbers for each question.

A1 What kind of organisation do you work for? Choose only one. 01

1 Internal to company in industry / services (Go to question A2)

2 External consultant or advisory body (Go to question A3)

3 Social insurance, or other insurance organisation (Go to question A4)4 Other incl. government inspectorate (Please specify)

……………………………………………………… (Go to question A4)

A2 Which description best classifies the main process of your organisation or 02company? 03

This list is based on the official NACE classification for your company. Please tryto circle only one category unless that is impossible, and then go to question A41 Agriculture or forestry 15 Furniture and woodworking2 Fishing 16 Recycling and waste3 Mining, quarrying 17 Electricity, gas and water4 Food, drink and tobacco 18 Building and construction5 Textiles, leather and clothing 19 Retail trade6 Paper and printing 20 Hotel and catering7 Oil and coal 21 Transport, post, communications and storage8 Chemicals 22 Financial services9 Rubber and plastics 23 Property & real estate10 Glass, ceramics and cement 24 Defence11 Metal manufacture and products 25 Education12 Machines and other technical equipment13 Electrical, electronics and optical instruments14 Car & other transport vehicle manufacture26 Health and welfare

27 Other services (Please specify)………………………..28 Other: (Please specify)……………………………

(Go to Question A4 )

A3 What sort of external advisory body do you work for? 04

1 Occupational health & safety service Go to question A4

2 Consultancy / engineering bureau Go to question A5

3 Industry, national or regional advisory body Go to question A4

|

4 |

Fire service Go to question A4 |

|||||

|

5 |

Other: (Please specify) ……………………………… Go to question A4 |

|||||

|

A4 |

What is the total number of people covered by your safety (advisory) responsibilities? External consultants |

05 |

||||

|

1 |

Under 100 |

|||||

|

2 |

101-500 |

|||||

|

3 |

501-1000 |

|||||

|

4 |

1001-5000 |

|||||

|

5 |

Over 5000 |

|||||

|

A5 |

Are other safety advisors employed in your organisation and if so, how many? |

06 |

||||

|

1 |

No others |

|||||

|

2 |

1 |

|||||

|

3 |

2-5 |

|||||

|

4 |

More than 5 |

|||||

|

A6 |

Does your work as safety advisor relate to more than one site/company? |

07 |

||||

|

1 |

Yes If so, how many? ………………………. |

|||||

|

2 |

No (go to question A8) |

|||||

|

A7 |

Are these sites/companies in more than one country? |

08 |

||||

|

1 |

Yes If so, which countries? ………………… |

|||||

|

2 |

No |

|||||

|

A8 |

Do you work full time or part time as a safety advisor? |

09 |

||||

|

1 |

Full time (Go to question A11) |

|||||

|

2 |

Part time |

|||||

|

A9 |

If you work part time, how many hours a week do you work on safety activities? |

10 |

||||

|

…………..Hours. |

||||||

|

A10 |

What other work do you do besides your safety activities? |

11 |

||||

|

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. |

||||||

|

A11 |

Are there other health, safety- or environment specialists working in your organisation? |

|||||

|

1 |

Occupational physician |

12 |

||||

|

2 |

Occupational hygienist |

13 |

||||

|

3 |

Occupational health nurse |

14 |

||||

|

4 |

Work and organisation specialist |

15 |

|||

|

5 |

Ergonomist |

16 |

|||

|

6 |

Environmental specialist |

17 |

|||

|

7 |

Fire specialist |

18 |

|||

|

8 |

Health physicist/radiation expert |

19 |

|||

|

9 |

Other: (Please specify) ……….………………………………………….. |

20 |

Section B Tasks

This section contains a list of tasks which you, in your safety professional role, may carry out. We would like to know which ones you do carry out and how frequently.

We have split this section into several parts, grouping together tasks which have something in common. We hope this makes it easier to understand and fill in. You may find most of your tasks grouped under one heading, but please go through all the sections and tasks and give an answer to each one.

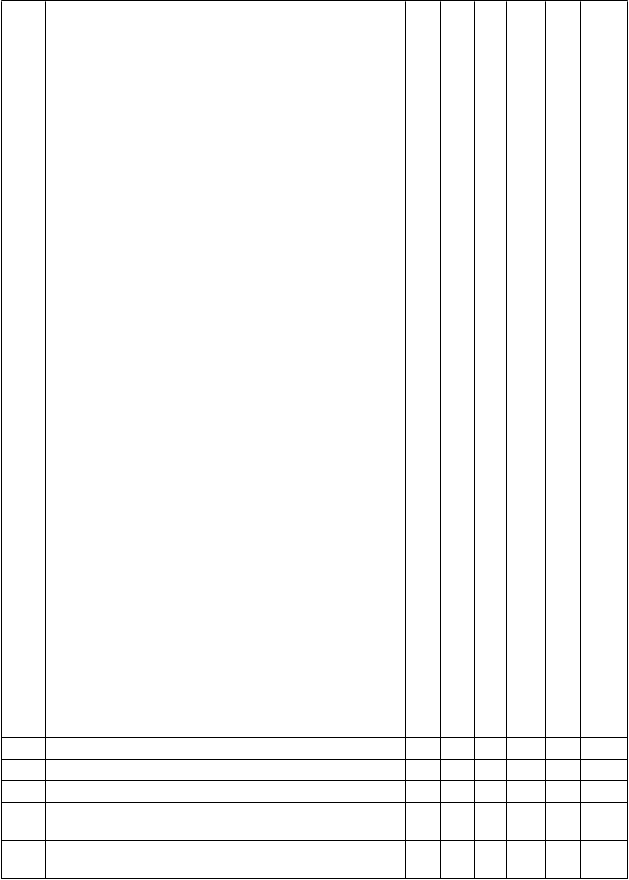

For each task please circle the shaded number that reflects best how frequently you personally carry out the task on average in your job. If you have never yet done a task, but it does form part of the responsibilities of your job, please circle 8. If the task mentioned is not part of your job please circle 9. Please circle only one answer per task.

Please circle only one number per task

|

1 |

Problem identification and analyses |

||||||

|

B1 |

Investigate & evaluate workplace or plant risks |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

21 |

|

B2 |

Perform job safety analyses |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

22 |

|

B3 |

Involved, as a member of a design team, in |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

23 |

|

integrating safety in the design of plant, processes, buildings, etc. |

|||||||

|

B4 |

Review a design, based on safety criteria, as |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

24 |

|

someone external to the design team |

|||||||

|

B5 |

Carry out risk analysis of projects, designs or |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

25 |

|

activities |

|||||||

|

2 |

Developing and implementing of solutions |

||||||

|

B6 |

Develop company policy for sustainable processes or |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

26 |

|

products |

|||||||

|

B7 |

Develop company environmental policy |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

27 |

|

B8 |

Prepare company policy related to safety of |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

28 |

|

machines, processes or workplaces |

|||||||

|

B9 |

Specify safety measures for machines, processes or |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

29 |

|

workplaces |

|||||||

|

B10 |

Develop/improve procedures for the safe use and |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

30 |

|

maintenance of machines, processes or workplaces |

|||||||

|

B11 |

Give instruction on the safe use and maintenance of |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

31 |

|

machines, processes or workplaces |

|||||||

|

B12 |

Check compliance with safety procedures for |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

32 |

|

machines, processes or workplaces |

|||||||

|

B13 |

Prepare company policy relating to dangerous |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

33 |

|

materials |

|||||||

Please circle only one number per task

|

B14 |

Specify safety measures for dangerous materials |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

34 |

|||||

|

B15 |

Design/improve the safety procedures for the use |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

35 |

|||||

|

and the storage of dangerous materials |

||||||||||||

|

B16 |

Check compliance with safety procedures for |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

36 |

|||||

|

dangerous materials |

||||||||||||

|

B17 |

Preparation company policy for PPE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

37 |

|||||

|

B18 |

Specify which PPE to purchase |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

38 |

|||||

|

B19 |

Design/improve procedures for the use and |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

39 |

|||||

|

maintenance of PPE |

||||||||||||

|

B20 |

Monitor the correct use of PPE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

40 |

|||||

|

B21 |

Develop the company safety management system |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

41 |

|||||

|

B22 |

Design performance indicators for the safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

42 |

|||||

|

management system |

||||||||||||

|

B23 |

Monitor the functioning of the safety management |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

43 |

|||||

|

system |

||||||||||||

|

B24 |

Propose improvements to the safety management |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

44 |

|||||

|

system or parts of it |

||||||||||||

|

B25 |

Prepare company policy on safety culture |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

45 |

|||||

|

B26 |

Assess the safety culture |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

46 |

|||||

|

B27 |

Propose improvements to the safety culture |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

47 |

|||||

|

B28 |

Lead or advise on organisational change to achieve |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

48 |

|||||

|

improvement in safety performance |

||||||||||||

|

B29 |

Check whether company policy or procedures |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

49 |

|||||

|

conforms to legal rules and regulations |

||||||||||||

|

B30 |

Prepare permits to work for dangerous work |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

50 |

|||||

|

B31 |

Check compliance with permits to work |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

51 |

|||||

|

B32 |

Member of the team for planning large scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

52 |

|||||

|

maintenance or modifications |

||||||||||||

|

B33 |

Assessing the plan for large scale maintenance and |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

53 |

|||||

|

modifications |

|

3 |

Training, information and communication |

||||||||||

|

B34 |

Design a safety campaign |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

54 |

||||

|

B35 |

Implement a safety campaign |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

55 |

||||

|

B36 |

Inform/discuss with safety representatives/ |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

56 |

||||

|

committee about possible risks and safety measures |

|||||||||||

|

B37 |

Inform/discuss with employees about possible risks |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

57 |

||||

|

and safety measures |

|||||||||||

Please circle only one number per task

|

|

B38 Inform/discuss with first line supervisors about possible risks and safety measures B39 Inform/discuss with line managers about possible risks and safety measures B40 Inform/discuss with top management about possible risks and safety measures B41 Publish information about safety in a company newsletter or other internal communication medium B42 Involved in defining selection criteria for the safety of new employees |

1 2 3 8 9 58

1 2 3 8 9 59

1 2 3 8 9 60

1 2 3 8 9 61

1 2 3 8 9 62

B43 Prepare company policy relating to safety training 1 2 3 8 9 63

B44 Design safety training programmes, or workshops 1 2 3 8 9 64

B45 Give safety training programmes, courses or workshops1 2 3 8 9 65

B46 Keep records of employees safety training 1 2 3 8 9 66

4Inspection and research

B47 Investigate accidents or incidents 1 2 3 8 9 67

B48 Investigate environmental incidents 1 2 3 8 9 68

B49 Keep statistics about accidents and incidents 1 2 3 8 9 69

B50 Keep statistics about sickness absence 1 2 3 8 9 70

B51 Make recommendations for improvement arising out of investigations

B52 Conduct workplace inspections of physical prevention measures1 2 3 8 9 711 2 3 8 9 72

B53 Conduct workplace audits of safe behaviour 1 2 3 8 9 73

B54 Conduct audits of the safety management system 1 2 3 8 9 74

5Emergency procedures and settlement of damage

B55 Prepare company policy on emergency procedures, intervention and first aid

B56 Prepare company policy on insurance and compensation

1 2 3 8 9 75

1 2 3 8 9 76

B57 Design/improve emergency procedures 1 2 3 8 9 77

B58 Organize practice of emergency procedures 1 2 3 8 9 78

B59 Manage a company fire fighting team 1 2 3 8 9 79

Please circle only one number per task

|

B60 |

Be a member of the company fire fighting team |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

80 |

|||||

|

B61 |

Give first aid courses |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

81 |

|||||

|

B62 |

Advise employer or employee about damage or |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

82 |

|||||

|

injury claims |

||||||||||||

|

B63 |

Act as expert witness in legal cases or claims |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

83 |

|

6 |

Regulatory tasks |

||||||||||

|

B64 |

Involved with making national/regional or industry |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

84 |

||||

|

wide safety laws and rules |

|||||||||||

|

B65 |

Be a member of a standards committee for product |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

85 |

||||

|

safety |

|||||||||||

|

B66 |

Be a member of a standards committee for safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

86 |

||||

|

competence or skills |

|||||||||||

|

B67 |

Be a member of a standards committee for safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

87 |

||||

|

management systems |

|||||||||||

|

B68 |

Take part in designing guidance or standards for |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

88 |

||||

|

safety courses or training at national or industry level |

|||||||||||

|

B69 |

Take part in the design and implementation of |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

89 |

||||

|

safety campaigns at national or industry level |

|||||||||||

|

B70 |

Advise on insurance premiums for a workplace or |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

90 |

||||

|

company |

|||||||||||

|

B71 |

Advise on damage claims |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

91 |

||||

|

B72 |

Answer questions from the public about safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

92 |

||||

|

7 |

Knowledge management |

||||||||||

|

B73 |

Read professional safety literature |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

93 |

||||

|

B74 |

Attend courses or workshops about safety subjects |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

94 |

||||

|

B75 |

Exchange knowledge and practical experiences with |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

95 |

||||

|

colleagues at local or national level |

|||||||||||

|

B76 |

Exchange knowledge and practical experience with |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

96 |

||||

|

colleagues at international level |

|||||||||||

|

B77 |

Write on safety in the professional or scientific |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

97 |

||||

|

literature |

|||||||||||

|

B78 |

Document the safety management system |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

98 |

||||

|

8 |

Management & Financial |

||||||||||

|

B79 |

Manage other safety or working conditions |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

99 |

||||

|

professionals |

|||||||||||

|

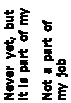

Please circle only one number per task |

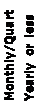

Weekly or more |

Monthly/Quart |

Yearly or less |

Never yet, but it is part of my |

Not a part of my job |

||||||||||||

|

B80 |

Prepare (parts of) an annual plan for safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

100 |

||||||||||

|

B81 |

Prepare (parts of) an annual report on safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

101 |

||||||||||

|

B82 |

Advise on/set the budget for safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

102 |

||||||||||

|

B83 |

Carry out cost-benefit analyses of safety measures or policies |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

103 |

||||||||||

Although we have tried to make this list as complete as possible, we know that this can never be done, given the great variety in what safety professionals do. If you think we have left out a significant safety task which you carry out, please insert it in the table below and tell us how frequently you carry it out. If this space is not enough, use an extra sheet.

B84 1 2 3 8 9 104

B85 1 2 3 8 9 105

Section C. Types of hazard/issue

This section contains a list of types of hazards/issues which you, in your professional role, may have to deal with. You may not have to deal with all of them, and certainly not equally frequently. Please circle the shaded number that reflects best whether, and if so how frequently, you deal with these hazards/issues. If the hazards/issues are present in the organisation(s) you deal with in your professional role, but you don’t have anything to do with advising about them, please circle 8. If the type of hazard/issue is not present in the organisation(s) at all, please circle 9.

Please circle only one number per hazard

C1 Inadequate lighting 1 2 3 8 9 106

C2 Extremes of cold or heat 1 2 3 8 9 107

C3 Noise 1 2 3 8 9 108

C4 Vibration 1 2 3 8 9 109

C5 Toxic and carcinogenic substances 1 2 3 8 9 110

C6 Biological risks 1 2 3 8 9 111

C7 Causes of other occupational disease 1 2 3 8 9 112

C8 Ionising radiation 1 2 3 8 9 113

C9 Non-ionising radiation 1 2 3 8 9 114

C10 Fire 1 2 3 8 9 115

C11 Explosion 1 2 3 8 9 116

C12 Electricity 1 2 3 8 9 117

C13 Machinery and installations 1 2 3 8 9 118

C14 Vehicles 1 2 3 8 9 119

C15 Human errors 1 2 3 8 9 120

C16 Subsidence and Collapses 1 2 3 8 9 121

C17 Falls 1 2 3 8 9 122

C18 Lifting 1 2 3 8 9 123

C19 Working posture 1 2 3 8 9 124

C20 Other physical workload 1 2 3 8 9 125

C21 Computers and VDUs 1 2 3 8 9 126

C22 Mental workload/Stress 1 2 3 8 9 127

C23 Bullying and harassment 1 2 3 8 9 128

C24 Violence against employees 1 2 3 8 9 129

C25 Alcohol or drugs 1 2 3 8 9 130

C26 Environmental pollution 1 2 3 8 9 131

C27 Lack of sustainability: production or products 1 2 3 8 9 132

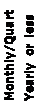

|

Please circle only one number per hazard |

Weekly or more |

Monthly |

Yearly or less |

Present in company but no task |

Not present in company |

||||||||||||

|

C28 |

Product liability |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

133 |

||||||||||

|

C29 |

Road/transport safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

134 |

||||||||||

|

C30 |

Accidents to patients, passengers, students or other clients |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

135 |

||||||||||

|

C31 |

External safety |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

136 |

||||||||||

|

C32 |

Other (Please specify) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

137 |

||||||||||

Section D Internal and external relations

This section contains a list of people and authorities with whom you may deal, in your role as safety professional. We would like to know whether you work with these people and how often. Please indicate that by circling one shaded number by each group, which best indicates your frequency of contact. If you have not yet had contact with these people, but it is part of your job, please circle 8. If it is not part of your job to have contact, please circle 9.

Please circle only one number per

category

D1 Occupational hygienist 1 2 3 8 9 138

D2 Occupational physician 1 2 3 8 9 139

D3 Ergonomist 1 2 3 8 9 140

D4 Work & organization psychologist 1 2 3 8 9 141

D5 Other medical specialists 1 2 3 8 9 142

D6 Visitors 1 2 3 8 9 143

D7 Employees 1 2 3 8 9 144

D8 Line management 1 2 3 8 9 145

D9 Top management 1 2 3 8 9 146

D10 Works council or equivalent 1 2 3 8 9 147

D11 Quality department 1 2 3 8 9 148

D12 Technical/maintenance service 1 2 3 8 9 149

D13 Personnel department 1 2 3 8 9 150

D14 Financial division 1 2 3 8 9 151

D15 Lawyer 1 2 3 8 9 152

D16 Designer 1 2 3 8 9 153

D17 Company planner 1 2 3 8 9 154

D18 Environmental expert 1 2 3 8 9 155

D19 Policy maker in Ministry 1 2 3 8 9 156

D20 Policy maker or planner in local authority1 2 3 8 9 157

D21 Government inspector (national, local) 1 2 3 8 9 158

D22 Occupational health & safety service 1 2 3 8 9 159

D23 Standards body 1 2 3 8 9 160

D24 Certification body 1 2 3 8 9 161

D25 Industry federation 1 2 3 8 9 162

D26 Professional association 1 2 3 8 9 163

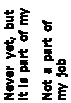

|

Please circle only one number per category |

Weekly or more |

Monthly |

Yearly or less |

No contact yet, but is part of job |

Contact is not part of my job |

||||||||||||

|

D27 |

Employers’ federation |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

164 |

||||||||||

|

D28 |

Trade-union official (local or national) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

165 |

||||||||||

|

D29 |

Insurer |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

166 |

||||||||||

|

D30 |

Inspector of (social) insurer |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

167 |

||||||||||

|

D31 |

Safety officers of other organizations |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

168 |

||||||||||

|

D32 |

Safety Committee or safety representative |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

169 |

||||||||||

|

D33 |

External safety consultant |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

170 |

||||||||||

|

D34 |

Educational establishment |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

171 |

||||||||||

|

D35 |

People living around the company |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

172 |

||||||||||

|

D36 |

Local fire service |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

173 |

||||||||||

|

D37 |

Other (Please specify)………… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

9 |

174 |

||||||||||

Section E Personal information

This section asks for some personal information. Please answer by circling the shaded number appropriate to you.

|

E1 |

How many years have you been working as a safety professional? |

175 |

|||

|

1 |

0-5 Years |

||||

|

2 |

6-10 Years |

||||

|

3 |

11-20 Years |

||||

|

4 |

More than 20 Years |

||||

|

E2 |

How many years have you worked as a safety professional with your present company? |

176 |

|||

|

1 |

0-5 Years |

||||

|

2 |

6-10 Years |

||||

|

3 |

11-20 Years |

||||

|

4 |

More than 20 Years |

||||

|

E3 |

Are you a member of a professional association related to safety? (Circle more than one if appropriate) |

||||

|

1 |

177 |

||||

|

2 |

178 |

||||

|

3 |

179 |

||||

|

4 |

180 |

||||

|

5 |

181 |

||||

|

6 |

Other (Please specify) ……………………….. |

182 |

|||

|

Each country should give the names of appropriate associations in spaces 1-5. If you do not need all the spaces, leave some blank, but keep ‘Other….’ As number 6. |

|||||

|

E4 |

What is your highest level of education? |

183 |

|||

|

1 |

|||||

|

2 |

|||||

|

3 |

|||||

|

4 |

|||||

|

5 |

|||||

|

6 |

|||||

|

Each country should add the appropriate descriptions of levels of education in their country, in the spaces 1-6. Start in 1 with the highest and work downwards. E.g. for most countries the highest will be ‘university degree’ and the lowest will be ‘secondary school’. If you do not need all 6 spaces, leave the last ones blank |

|||||

|

E5 |

Which training for a safety qualification have you completed? (Circle more than one if appropriate) |

|||||||||

|

1 |

None |

184 |

||||||||

|

2 |

185 |

|||||||||

|

3 |

186 |

|||||||||

|

4 |

187 |

|||||||||

|

5 |

188 |

|||||||||

|

6 |

Other (Please specify) ……………………….. |

189 |

||||||||

|

Each country should insert the names of the appropriate courses leading to a safety qualification in their country in the spaces 2-5. If you do not need all spaces, leave some blank, but keep ‘Other….’ As number 6. |

||||||||||

|

E6 |

What is the job title of your safety function? …………………………………………… |

190 |

||||||||

|

E7 |

What is your gender? |

191 |

||||||||

|

1 |

Male |

2 |

Female |

|||||||

|

E8 |

What is your age? |

192 |

||||||||

|

1 |

20 - 24 year |

5 |

41 - 45 year |

|||||||

|

2 |

25 - 30 year |

6 |

46 - 50 year |

|||||||

|

3 |

31 - 35 year |

7 |

51 - 55 year |

|||||||

|

4 |

36 - 40 year |

8 |

55 year or older |

|||||||

|

E9 |

Have you any additional comment you wish to make about your role or tasks, or about this questionnaire? |

193 |

||||||||

Thank you for your assistance. It will make an invaluable contribution to our project, to try and understand the role of the safety professional better.

Please return the completed questionnaire to:

If you have questions or comments you can also phone, fax or e-mail to:

Papers relacionados