Background - the subculture of care

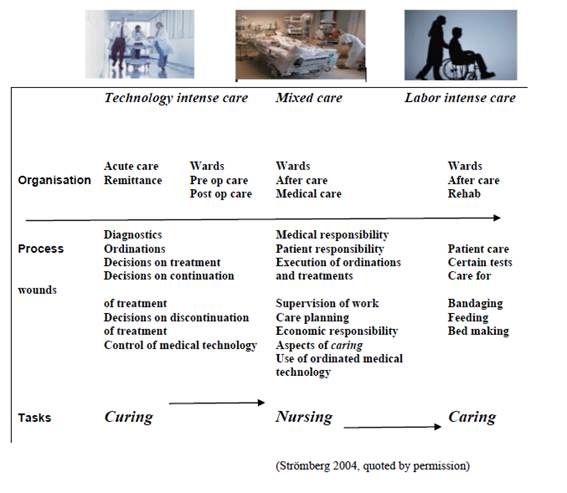

The process of the patient in the system of care can be described as a trip between three different subsystems with different qualities, different roles and functional conditions (Strömberg 2004).

In the first, initial subsystem - Curing - the Doctors and the medical specialists rule; they diagnose, intervene, operate and prescribe. Here, medical competency rules absolutely; it's strictly hierarchical, it governs, prescribes and controls. This is the inner circle of care; the Shaman rules autocratically, is most often a male, has the highest status, highest pay and the longest working hours (Ranehill 2002; Larsson 2013).

After the audience and treatment with the Physician, the sick person moves into the next subsystem to be taken care of and nursed. Here, the prescriptions and decisions of the medical specialists will be executed; medicine injected, treatments carried out, examinations undertaken and the general condition of the patient monitored. This subsystem - Nursing - is handled by Nurses, traditionally and still mainly women. The medical competency is operational, precisely defined and completely subordinate to the doctor. The decision level is conditional and depending on the rank in the hierarchy of the department, status is medium high, salaries lower and working hours regulated.

The third subsystem handles the manual and physical care work; wounds are washed and bandaged, beds are cleaned, diapers changed, food is served and certain tests are collected. This subsystem - Caring - is traditionally and to 90% staffed by females, who perform duties mainly the same as women always have done in the reproductive sphere. In this subsystem you have no or very low medical competency, low status, low salary, regulated working hours and heavy work (Rasmussen 2004).

Table 1The subsystems of medical care

Care-related infections

A measurement in Swedish hospitals in 2008 indicated that 10% of admitted patients had acquired some form of care-related infection (Socialstyrelsen 2008). The most common acquired infections were to the urinary tract, to skin and wounds and pneumonia.

|

The incidence of different kinds of care-related infections in the USA 1993–1995 (CDC 1995), Denmark 1999 (Christensen & Jepsen 2001) and Norway 1996–1998 (Andersen et al 2000). |

|

Type of infection Proportion of all care-related infections (%) |

|

USA Denmark Norway |

|

1993–1995 1999 1996–1998 |

|

Urinary tract infection 27,2 26,6 30,8 |

|

Pneumonia 17,3 17,4 17,7 |

|

Post-operative wound infection 18,7 25,0 19,2 |

|

Primary bacteraemia 15,8 5,1 6,2 |

|

Other infection 21,0 23,9 26,3 |

Table 2 Proportion of different kinds of care-related infections measured in the USA, Denmark and Norway

A comparison of studies of the incidence of care-related infections between the USA, Denmark and Norway shows that urinary tract infections are the most common (Table 2). A Norwegian study covered around a quarter of all nursing homes in the country and was carried out in 2002 and 2003. Four types of infections were measured (urinary tract, skin, pneumonia and surgical wounds). The prevalence of care-related infections varied between 6.6 and 7.3 per cent. Of the diagnosed infections, 50 % were to the urinary tract, 25 % were skin infections, 19 % pneumonia and 5 % infections to surgical wounds (Eriksen et al 2004).

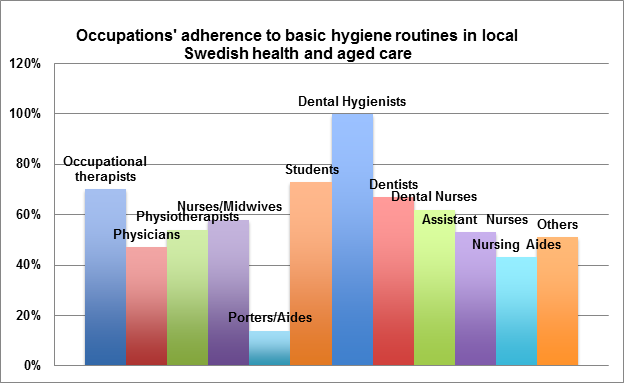

Graph 1 Occupations’ adherence to basic hygiene routines in the local Swedish health and aged care 2013 (SKL 2014)

In the bi-annual prevalence measurements on the adherence to basic hygiene routines undertaken in a random selection of Swedish councils, 3347 healthcare workers in 35 councils were observed at work during the fall of 2013. Eighty per cent of the staff investigated worked in aged care. The basic hygiene routines are operationalized as disinfecting hands after patient work, disinfecting hands before patient work, correct use of gloves, correct use of apron, correct work clothes, short or covered hair, no rings, bracelets or wristwatch (SKL 2014).

The adherence to the basic hygiene routines varies remarkably between different occupations in care work; only 43% of Nursing Aides and 47% of Physicians correctly adhere to the seven aspects of hygiene in their work.

Method

In a project to develop better hygiene management in care organizations, one large special accommodation establishment with 100 aged residents in 9 different wards was selected for investigation (IMI 2012). The intervention at this special accommodation, with staff workshops, bacterial activity screening of the premises and periods of participant observation, started in November 2012.

The annotated medical journals of each resident, kept by the in-house Nurses, were screened for cases of care-related infections for the period July 2011 through October 2012. Defined infections, treated with some form of antibiotic drugs, were recorded in the Nurses’ journals over the whole accommodation for the period. Cases of medication noted without a recorded infection were not included in the study.

Participant observation was conducted in two of the nine wards on 16 occasions, 2 hours of observation at different times of the day/night; one staff at a time was observed, during 4 working weeks in September 2013, a year after the start of the project. Seventy-eight different work operations were observed and analyzed. The same researcher performed all the observations.

Results

Infection risk according to journal data

A total of 123 defined infections treated with an antibiotic, were recorded over 16 months. Against an exposure of 121,4 years of care, this facility produces one care-related infection per resident and year (Table 3).

However, the risk of infection varied considerably between wards; the semi-closed dementia wards (3, 9) had very few infections, two of the wards (5, 6) had nearly double the incidence compared to the rest of the wards.

|

All indicated infections according to Nurses’ journals, 16 months (2011-07-01 – 2012-10-31) |

|

Ward Days in care Infections R* |

|

1 6344 15 0024 |

|

2 9272 25 0026 |

|

3 3904 2 0005 |

|

4 4392 11 0025 |

|

5 6832 26 0038 |

|

6 4880 19 0038 |

|

7 4880 10 0021 |

|

8 4392 11 0025 |

|

9 3416 4 0012 |

|

Total 48312 123 |

Table 3 Wards, number of days exposed, number of infections, infection risk 16 months, 100 residents (2011/07 – 2012/11). * (Deceased are not included; they represented 3994 days in care, 10 infections, R=.0025 during the period)

Participant observations

Seventy-eight tasks with a potential risk of spreading infection were observed during a total of 32 hours of care work.

|

Number of tasks with infection risk |

Observations/deviations |

||||||||||||||

|

Took off gloves after care task |

Put gloves on too early |

Disinfected hands after care task |

Handled garbage bag with clean hands/gloves |

Handled dirty laundry with clean gloves |

Put apron on too early |

Took apron off after hygiene task |

|||||||||

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

||

|

21-06 |

31 |

29 |

7 |

2 |

34 |

26 |

2 |

1 |

21 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

08-10 |

16 |

4 |

14 |

5 |

8 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

|

13-15 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

23 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

17-19 |

9 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

17 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

|

19-21 |

15 |

15 |

2 |

3 |

10 |

25 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Total |

78 |

60 |

29 |

17 |

65 |

96 |

11 |

12 |

30 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

15 |

7 |

10 |

|

Cont. |

Observations/deviations |

|||||||||||||||

|

Touched the phone with clean hands |

Opened kitchen garbage bin with gloves/used the pedal |

Disinfected hands after using garbage bin |

Disinfected hands after throwing out garbage bag |

All of garbage sack/trolley process with gloves |

Disinfected/ washed hands after garbage sack/trolley process |

Clean the dishwasher wearing gloves |

Disinfected/washed hands before cooking |

|||||||||

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

21-06 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

08-10 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

13-15 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

17-19 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

19-21 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Total |

21 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

11 |

0 |

Table 4 Observations of and deviations in hygiene routines, 2 wards in special accommodation, 16 staff, 16 occasions/2-hour periods, September 2013.

If we assume these observations to be representative of the actual staff work routines in hygiene tasks in the two wards, we can conclude that

- 12% put their apron on too early before doing a hygiene task,

- 58% keep their apron on after finishing a hygiene task.

- 20% put their gloves on too early before doing a hygiene task,

- 32% keep their gloves on after finishing a hygiene task,

- 90% disinfect their hands after finishing a hygiene task.

Observations of handling the garbage and the dirty laundry indicate that routines here are unclear. However, staff seems to be aware of the associated infection risks in food preparation.

Discussion and conclusion

It is obvious from the observation data that a considerable proportion of the staff in the wards of this special accommodation deviate from the recommended basic hygiene routines in their close personal care of the residents. The adherence to basic hygiene routines seems to be in line with the levels reported nationally (see Graph 1).

To prevent the spread of infection requires a detailed understanding of how the contamination of the local environment can work. We believe that there might be a cognitive problem in identifying that, which represents an immediate risk of infecting yourself, compared to the risk of spreading something contagious in the environment (Sachs 1983).

The risk of being infected by touching the perceived source of contamination is easily understood. The fact that the contaminated glove or apron might pass on the infection to the table, the door knob, the light switch or the telephone is not perceived as an immediate threat to your own health. In fact, it might not be understood as an infection risk at all.

From the results of the National prevalence measurement, it is obvious that the level of qualification in health care does not explain adherence to basic hygiene routines. In relation to understanding how contamination operates in the environment, Physicians might suffer from the same cognitive difficulties as the Nursing Aides.

The basic hygiene routines, including a practical knowledge on contamination in the local health care environment, should be seen as a required professional competency in health care staff and should be taught to Nursing Aides and Physicians alike.

Evidence from the medical and lay literature suggests that the role model could play a pivotal role in changing human behaviour (Eggiman et al 2000, Sherertz et al 2000). By contrast, negative role models could also be influential; poor practice can also be learned at the bedside (Stone et al 2001, Lankford et al 2003).

Junior staff and students who were taught to hand-wash abandoned their habit when others, especially more senior staff, did not bother (Larson et al 1986). Nurses have higher adherence rates than Physicians and because poor physician adherence to hand hygiene is among the reported reasons by Nurses for the difficulty in ensuring sustained adherence, improvement in physician compliance might improve overall adherence among all health care staff.

(Pittet et al 2004)

References

Andersen BM, Ringertz SH, Petersen Gullord T, Hermansen W, Lelek M, Norman B-I et al. A three-year survey of nosocomial and community-acquired infections, antibiotic treatment and re-hospitalization in a Norwegian health region. J Hosp Infect 2000;44:214–23.

CDC NNIS System. National nosocomial infections surveillance (NNIS) Semiannual Report, May 1995. Am J Infect Control 1995;23:377–85.

Christensen M, Jepsen OB. Reduced rates of hospital-acquired UTI in medical patients. Prevalence surveys indicate effect of active infection control programmes. J Hosp Infect 2001;47:3–40.

Eggimann P, Harbarth S, Constantin MN, Touveneau S, Chevrolet JC, Pittet D (2000) Impact of a prevention strategy targeted at vascular-access care on incidence of infections acquired in intensive care. Lancet. 2000;355:1864-8.

Eriksen HM, Iversen BG, Aavibland P. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities in Norway, 2002 and 2003. J Hosp Infect 2004;57:316–20.

IMI (2012) Innovation against Infection. Application to Vinnova. Swedish Research Institute (SP).

Lankford MG, Zembower TR, Trick WE, Hacek DM, Noskin GA, Peterson LR (2003) Influence of role models and hospital design on hand hygiene of healthcare workers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:217-23.

Larson E, McGinley KJ, Grove GL, Leyden JJ, Talbot GH (1986) Physiologic, microbiologic, and seasonal effects of hand-washing on the skin of health care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 1986;14:51-9.

Larsson, TJ (2013) Sjukvårdens subkultur –ett hinder för säker vård? i Ödegård, S (Ed) Patientsäkerhet: teori och praktik. Liber förlag, Stockholm.

Pittet, D, Simon, MA, Hugonnet, S, Pessoa-Silva, CL, Sauvan, V, Perneger, TV (2004) Hand Hygiene among Physicians: Performance, Beliefs and Perceptions. Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol141(1) pp 1-9.

Ranehill, E (2002) Social snedrekrytering till högre studier . Institutet för framtidsstudier 2002:10.

Rasmussen, B (2004) Between endless needs and limited resources: The gendered construction of a greedy organization. Journal of Gender, Work and Organization , Vol 11 (5) pp 506-525.

Sachs, L (1983) Evil eye or bacteria. Turkish migrant women and Swedish health care. Stockholm Studies in Anthropology. University of Stockholm, ISBN 91-85284-22-X.

Sherertz RJ, Ely EW, Westbrook DM, Gledhill KS, Streed SA, Kiger B, et al. (2000) Education of physicians-in-training can decrease the risk for vascular catheter infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:641-8.

Strömberg, H (2004) Sjukvårdens industrialisering. Mellan Curing och Caring –sjuksköterskearbetets omvandling. (The Industrialization of Medical Care. Between Curing and Caring – the Development of Nursing Work. In Swedish).Doctoral Thesis. Dep of History of Economics, Umeå Universitet.

SKL (2014) Punktprevalensmätning av följsamhet till basala hygienrutiner och klädregler. Kommunernas resultat hösten 2013. Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting.

Socialstyrelsen (2008) Vårdskador i somatisk slutenvård. Rapport 2008-109-16.

Stone S, Teare L, Cookson B. (2001) Guiding hands of our teachers. Hand-hygiene Liaison Group [Letter]. Lancet. 2001;357:479-80.

Papers relacionados