Universitat de València - Unitat d’Investigació de Psicometria - Facultat de Psicología - Avda. Blasco Ibañez, 21 - 46010 València - SpainTel: +34 96 386 46 99 - Jose.L.Melia@uv.es www.uv.es/seguridadlaboral

Universitat de València - Unitat d’Investigació de Psicometria - Facultat de Psicología - Avda. Blasco Ibañez, 21 - 46010 València - SpainTel: +34 96 386 46 99 - Jose.L.Melia@uv.es www.uv.es/seguridadlaboral

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

In clear and simple terms, the purpose of the prevention is to have people work in safety, that is, without the risk of work-related accidents, professional illnesses and other things harmful to health. Therefore, an important, simple and legitimate question is: What is needed so that people can work safely? This article presents what I call the “triconditional model of safe work”, which is essentially a simple and clear answer to this very important question.

This triconditional model of safe work has four qualities that make it useful: First, it is simple and didactic, which favours its communication in safety training. Second, it makes it possible to guide an appropriate safety diagnosis, that is, an evaluation of risks that really aids in prevention. Third, the diagnosis is clearly linked to the intervention; in other words, it becomes clear which groups of intervention techniques correspond to which group of problems detected in the diagnosis. Finally, the model makes it possible to relate the three conditions with five states of safety behaviour, thus providing an orientation and a goal for the gradual development of the preventative action.

Keywords

Keywords

Safe work, occupational risk, risk prevention, accident prevention

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Curiously enough, the sciences of safety, with their diverse multi-disciplinary facets, are the sciences of uncertainty. Companies and human organizations in general develop and thrive in changing contexts with many types of uncertainties, with regard to markets, finances, etc. The type of uncertainty that the sciences of safety and prevention deal with can cause damage to people or goods in a specific and tangible way. The objective of the prevention then is to limit, reduce or eliminate the uncertainty so that the behaviour of the system (management, methods, workers, materials and environment) avoids this unwanted, sudden or progressive damage.

In clear and simple terms, the purpose of the prevention is to have people workin safety, that is, without the risk of work-related accidents, professional illnesses and other things harmful to health –or at least with as little risk as possible given the current state of technological development- and keep this risk under control. Therefore, an important, simple and legitimate question is: What is needed so that people can work safely?

This article presents what I call the “triconditional model of safe work”, which isessentially a simple and clear answer to this very important question (Meliá, 2007).

This triconditional model of safe work has four qualities that make it useful:

• First, it is simple and didactic, which favours its communication in safety training.

• Second, when its meaning is understood, it is also clear that it makes itpossible to guide an appropriate safety diagnosis, that is, an evaluation of risks that really aids in prevention.• Third, the diagnosis is clearly linked to the intervention; in other words, itbecomes clear which groups of intervention techniques correspond to which group of problems detected in the diagnosis. This point is very important because it clarifies in a simple way what the different groups of preventative action techniques are for and, most of all, what they are not for. Sometimes some of these techniques, especially some related to the human factor, are applied without having a very clear idea of when they are appropriate and when not, and what can be expected from them.• Finally, the model makes it possible to relate the three conditions with fivestates of safety behaviour, thus providing an orientation and a goal for the gradual development of the preventative action.

2. PREVENTION REQUIRES A CONTINUOUS CYCLE BASED ON THE DIAGNOSIS

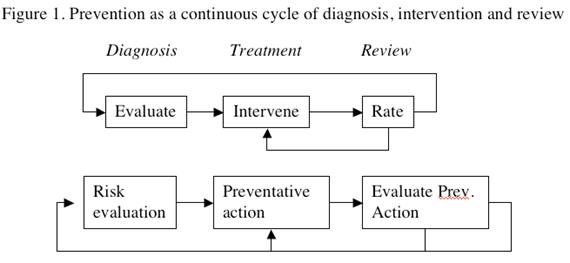

In order to understand the model and its implications, it is necessary to make clear that this start from the assumption that prevention (Figure 1) is an activity that takes place in a continuous cycle through three phases:

(a) the evaluation or diagnosis; that is, Where are we in terms of safety?, Whatproblems do we have to deal with?, What are our strengths?(b) the treatment or intervention; that is, What methods are indicated for these problems in this situation? How do we plan and carry out their effective application?, and(c) the rating; How do we evaluate the results obtained? What changes did thisintervention produce in terms of safety indicators, accident indicators and economic indicators? What modifications should be made in the intervention and, if necessary, in the diagnostic procedures themselves?

In professional terms in the prevention of work-related risks, these three phases are usually identified with the concepts of (a) evaluation of risks, (b) preventative action and (c) evaluation of the preventative action.

The key idea is that the intervention depends on –and not only follows in time- the diagnosis. Therefore, an evaluation of risks is useful in so far as it tells precisely in what aspects we have to intervene, in what zones or parts of the organization, and with what specific techniques.

3. WHAT IS NEEDED SO THAT PEOPLE CAN WORK SAFELY?

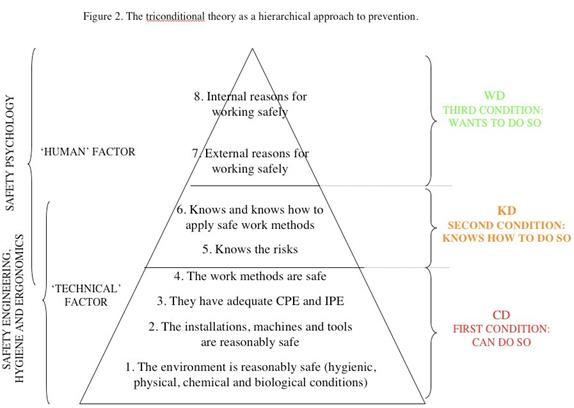

This is not just an important question, but rather it is the most important question, in prevention. It is obviously a complex multi-disciplinary question. However, expressed in a didactic way that helps us to structure our concept of prevention, everything that is needed so that people can work safely can be summed up in a simple way in three broad conditions (Figure 2):

• First Condition: That they can do it (CD),

• Second Condition: That they know how to do it (KD), and

• Third Condition: That they want to do it (WD). These are the three conditions of safe work.

The three are necessary conditions, and none of them is sufficient by itself; that is, if only one of them is lacking, we will not have safe work. All three are necessary, and the three together, addressed appropriately and taken as a unit, are enough to produce safe work. Therefore, if we want real safety, and not just a formal one, in the safety diagnosis we have to check whether all three conditions are met –and not just one or two of them.

The three conditions apply at the individual work level, for a worker, a boss or amanager who has a given job. But they also apply quite logically to collectives, work groups, departments, sections, units or companies as a whole. In other words, in order for an employee to work safely, he or she must be able to do so, know how to do so, and want to do so. And the same thing can be said about a company: in order for it to function safely, it must meet these three conditions. In other places, we have explained some aspects of this theory in detail, and we have also described part of this triconditional analysis for companies (Meliá, 2007); here we will focus on the individual level, as seen from the internal point of view of a company.

If we analyze the three conditions from the internal point of view of a company, in order for an employee to be able work safely (CD condition),(1) the environment in which he/she carries out his/her work, understood in a broader sense, including the hygienic, physical, chemical and biological conditions, must be reasonable safe;(2) the installations, machines, tools, materials, etc., must be reasonably safe;(3) he/she must have access to collective and/or individual protection equipment that is appropriate and adequate; and(4) he/she must have reasonably safe work procedures.

“Reasonably safe” in this context means that the risks are minimized or eliminated to a degree that is reasonable, given the current development of the technique and the basal risk characteristic of and inherent to the activity and the job. If these four groups of sub-conditions that make up the first or CD condition are present, it can be said that the worker has a reasonably safe job in a reasonably safe context. This is a necessary condition for safety, but it is not enough.

In order for the worker to really work safely, it is not enough for the job to be reasonably safe. The PH condition acts as an enabler, but it does not necessarily lead

to or induce a safe job. In order for someone to paint a good oil painting, he/she needs an appropriate place, oil paints and brushes…, but all of this does not guarantee that he/she will paint a good picture, or even paint at all!

In order for a worker to work safely, in addition to being able to do so, he/she has to “know how to do so” (KD condition). “Knowing how to do so” in terms of safety means that he/she knows the risks of his/her job and the environment and knows how to deal with them by using safe work methods. Every worker must know how to work safely in order to work safely. Some important failings in safety can occur because of ignorance about safe work methods or the actions that must be taken to do a certain task in a safe way. What is needed is not just theoretical knowledge, but also practical knowledge, the ability to know how to do things in a safe manner.

The fact that the person “knows how to work safely” is also an enabler, in thiscase an internal enabler of the person, not of the job itself. It is an enabler that “goes with the person” and that depends on his/her training, professional background and prior education. However, the fact that the person knows how to paint does not guarantee either that he/she will paint a good picture, even though he/she also has the necessary means.

There is another condition associated with the person that is also necessary, the third condition in the triconditional model. This third condition is that the person “wants to do so” (WD condition). Saying that a person “wants to do so” is a simple way to refer to the question of motivation. Motivation isn’t a condition of the job either–although the job can help in a definitive way- but rather it is a complex function ofnumerous internal and external variables.

In many contexts there is a safe way to do things and one or more unsafe ways. Contrary to what is often conveyed in prevention training, many times one or

some of the unsafe ways are not irrational. On the contrary, many unsafe ways of working that are common in many jobs involve a controlled risk, or a risk the person believes is controlled, and many immediate advantages. For example, not wearing an PPE usually has immediate advantages in terms of comfort and, even, the ease of doing the task more comfortably. Curiously, in these contexts the person who does not put on the PPE literally takes an ergonomic action, adapting the job to the person and reducing fatigue and making the job easier. Thus, many unsafe behaviours are not exactly irrational. Of course, I am not defending unsafe work, but to make prevention effective it is necessary to understand that the person may have internal and external reasons for doing a job safely, and he/she usually has internal and external reasons for opting for a less safe or clearly unsafe way as well.

To satisfy the WD condition, the balance between internal and external reasons must lead the worker to opt for the safe way of doing the job.

Only when the worker can do the job in a safe way (CD condition), he/she knows how to do so (KD condition), and the balance of motivation leads him/her to opt for the safe way (WD condition), will we have safe work.

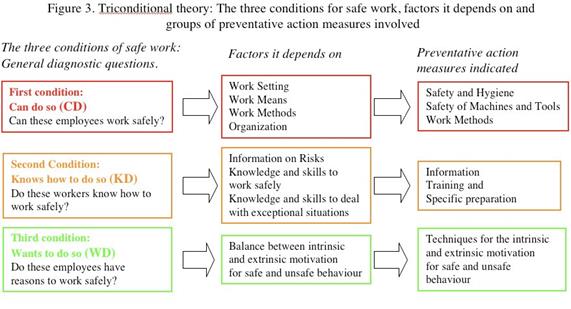

4. PREVENTATIVE ACTION FACTORS AND MEASURES FOR EACH CONDITION

This simple formulation of the three conditions would be merely didactic if not for the fact that each of the three conditions depends on different groups of factors. For this reason, both the diagnostic methods and the preventative action measures indicated for each condition are clearly distinct (figure 3).

As each condition clearly depends on different groups of factors, the threeconditions become three key diagnostic questions that must be asked of each unit under analysis. The generic diagnostic question in safety is: What is going wrong and what works well in prevention in this company? This basic question breaks down into three questions, one for each condition. That is, can people work safely here? Do they know how to work safely? Do they want to work safely?

It is clear that these three questions are still generic and must be broken downin each company and each job into a collection of more specific questions dealing with the main groups of factors that each one refers to. Thus, a risk evaluation consists of identifying the specific appropriate questions in each company and job and applying the appropriate diagnostic methodologies to obtain answers based on data.

Figure 3 shows a brief version of the main groups of factors that must beconsidered to verify that each of the three conditions is met.

The first condition, “to be able to do so” (CD), is the condition most tied to traditional technical factors of safety and hygiene. In many companies seriously concerned with safety, without being especially aware of it, this is the condition that receives the most attention or almost the only one that receives attention. There are four large groups of basic factors on which this CD condition depends: (1) a reasonably safe and healthy environment, (2) installations, materials, machines and tools that are reasonably safe, (3) collective protection equipment (CPE) and appropriate individual protection equipment (IPE) available and correctly maintained wherever necessary, and (4) safe work methods.

The diagnostic methodologies for the CD condition range from diverse specific technical measurements (e.g., of pollutants or noise) to direct observation (e.g., use of check-lists to verify the presence or absence of certain risks) or the analysis of work flow and methods.

When the diagnosis of the CD condition indicates deficits in it, the preventativemeasures available in terms of hygiene, safety, work methods or the organization of the work and prevention should be used, depending on the deficit and the technology available. This is an area that is well known to the majority of those who work in prevention, and the one that receives the most space in their training.

This CD condition, with its four large groups of factors, is the first that should be reviewed. The current legal terminology itself (“risk evaluation”) seems to suggest that safety and health depend on this condition. And indeed it does depend on it. But it doesn’t only depend on this condition. The CD condition is only one of the three legs of the stool.

If only the CD condition is reviewed and paid attention to, necessary but notsufficient, we will have the setting for a safe company, but not necessarily a safe company. As far as human behaviour is relevant –and it is rarely completely irrelevant– a work environment can be clearly unsafe in spite of positively satisfying the diverse factors of the CD condition.

The second condition, “knowing how to do so” (KD), refers to the need for each member of the company to know, in a clear and operative way, about the inherent risks in his/her decision-making area, and to know about and know how to use the safe work methods.

Without knowledge and specific professional ability in the area of safety it is impossible to work safely. It is necessary for people to know how to work safely in order to achieve safety and health.

However, by itself this condition is not sufficient either. It is commonly acknowledged –in the work setting and outside of it- that people often can do things in a safe way (CD condition), and know perfectly well about the risks of not doing so, and know perfectly well how to do things well (KD condition), but they choose to do things in an unsafe way.

When reflecting on this, in the beginning it seems impossible because we tendto think that if people can and know how to do things safely, they will do them safely. But this is quite often not true. Imagine, for example, how frequently appropriate IPE are available and not utilized, the safety mechanisms are shut off in some way, or the safety and prevention protocols are skipped, even after having received the pertinent information and training.

We find clear examples that training and information by themselves are not enough in numerous risk behaviours in everyday life. For example, everyone knows that it is necessary to use a seat belt. We receive specific information about it, and we

continuously see expensive advertising campaigns about it. However, not using the seat belt in Spain is still currently directly responsible for more than 500 of the more than 3,000 annual traffic deaths. As another example, everyone knows that smoking kills in a way that is also slow, painful and tragic. In fact, it says so on all the cigarette packages. However, this deliberate unsafe behaviour is directly responsible in Spain for more than 50,000 deaths annually directly attributable to smoking and 1,500 deaths of passive smokers, -a term that is not very respectful of these 1,500 deaths annually because, in reality, they never smoked. Knowing the risks and knowing how to do things in a safe way is definitely necessary, but it is not enough to ensure that we actually choose the safe behaviour, either at work or in the rest of our lives. Even among prevention experts or future prevention experts, especially aware and concerned about the topic, if we examine our consciences, we will see that we often commit risky behaviours, for example, in traffic (speed, crossing at crosswalks, etc.). Is it that we can’t or don’t know how to perform the alternative safe behaviour?

Two important observations about the second or KD condition are in order. First, it involves developing skills, that is, knowing how to make the way of working in this specific industry safe in a practical, real and suitable manner, and not just spreading knowledge. The theoretical training, from the classroom, in writing, audiovisual, on electronic forms or in intranet, is a complement that is often useful and necessary, but generally clearly insufficient and inadequate for developing and testing real safe working skills. For this reason, verifying that a company has signed the papers witnessing that they have provided a few hours of training is practically verifying nothing. The KD condition has to be verified by checking that each employee knows how to do his/her job in a safe manner and that he/she knows the risks inherent in the environment and how to deal with them. It is a condition of the employee, and not of some papers kept by management.

Second, the KD condition affects all the members of the company, and not justeach worker or employee. It also affects each supervisor, each intermediate boss and each manager in a special way. Knowing the methods of safe work involves not only those methods having to do with mechanical, manual or technical actions, but also those related to decision-making; the latter affect all the levels of workers, but especially the bosses and managers.

The safety training model oriented exclusively toward the last element in the line –the worker at the base of the organizational pyramid– is obsolete and harmful. In many contexts, it is thought that the majority of the safety accidents and incidents “originate within the organizational and managerial sphere” (Reason, 1993). Therefore, it is important for all the managers, including those business owners who take care of their businesses personally, to receive explicit training in safety. As one goes up the hierarchical pyramid, the responsibility in the area of safety increases. It is absurd to train the workers and not require much more serious and rigorous training for those who make the decisions.

Meeting the second or KD condition throughout the entire hierarchical line is necessary for obtaining safety. Thus, the safety diagnosis –what we now refer to with the partial and obsolete term “risk evaluation”– must evaluate whether the condition is fulfilled in the entire organization, that is, whether all the members of the organization have the knowledge and skills necessary to work safely. Given that the risk is shared, the presence of members in the company without the correct safety training, information, knowledge and skills is a risk for everyone, especially those who hold positions of responsibility. When there are deficiencies in the KD condition, it is clear that the intervention techniques indicated are specific information, training and preparation, always followed by a real evaluation, not just a formal one or one based on attendance.

As we mentioned above, satisfying the first and second conditions, that is,

being able to and knowing how to work safely, is unfortunately not enough. It is also necessary to want to work safely (WD condition).

Wanting to work safely really depends on a balance between the reasons for adopting unsafe solutions and the reasons for adopting a safe method or methods. As this condition is not mentioned in the legislation or in the majority of the training material for prevention technicians, the latter are trained in the ingenuous psychology that people who are mentally healthy will simply want to work safely when they know about it and can, at least as far as they are “aware” or have a “positive attitude”. This ingenuous psychology is far from reality and sometimes diametrically opposed to it. Of course, if you ask people if they want to work safely, the usual answer is yes, but in reality many of these same people find it easy to skip safety protocols “only once in a while because there is a situation where it is urgent to get out this product”. What people say does not properly represent the true motivational balance, or at least it is not a good way in itself of evaluating motivation.

As this is a topic that is not seriously approached in the training of preventiontechnicians, sometimes this seems to be a question of common sense, or something we can’t do anything about. Or we think training is enough to produce motivation. This latter idea –clearly erroneous- is quite popular, and many defend it with all their might against the decades of extensive scientific evidence that shows just the opposite.

The purpose of this article is not to explain the appropriate preventative action techniques to achieve the fulfilment of the WD condition –or the safety and hygiene techniques for the first condition or the training techniques for the second. However, it should be clear that the balance of motivation toward safe and unsafe work can be analyzed in a diagnostic process in a company, and that there are specific techniques of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation that are perfectly applicable in companies to stimulate safe work. We are referring to safety intervention techniques developed by the international and national research, contrasted and validated in numerous companies (in industry, in the military, in mines, in services companies, in construction

…).

5. THE TRICONDITIONAL MODEL AS A CYCLE OF IMPROVEMENT

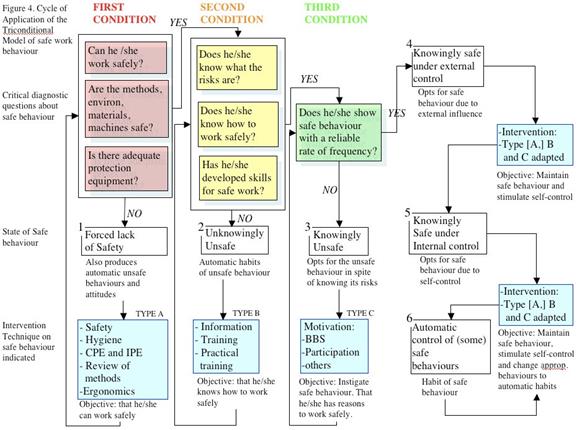

The triconditional model can be seen as a cycle of improvement in which an employee, a group, a department or a company to which it is applied can experience a positive evolution.

If a worker cannot work safely, for example because the methods are not safeor he or she doesn’t have the appropriate IPE, then he/she is in a state we call forced lack of safety. The first objective is that people can work safely. In order to do so, it is necessary to work on a group of corresponding safety and hygiene factors.

If a worker can work safely, but does not know how to work safely –forexample, because he/she isn’t aware of the consequences of his/her decisions about safety– then this worker is in a state we can classify as unknowingly unsafe. Information and training are decisive and extremely useful tools here.

But if the worker can work safely (CD condition) and knows how to work safely(KD condition), but even then does not work safely often enough in a reliable way, then the worker is knowingly unsafe. He or she is choosing unsafe ways of working probably because the balance of motivation is not well-defined. Therefore, it is important to work on the motivation with the techniques that are technically appropriate.

In general, the final objective is to have workers that work in a knowingly safe way controlled by internal motivation. For some work behaviours and sequences that can be the object of automatic (human) behaviour, that is, without conscious control, it is possible to try to get the worker to perform them in an unknowingly safe way. For the majority of the tasks, the final objective, however, lies in being knowingly safe under the control of internal motivation. This is an admirable objective. In most cases to reach it, techniques would have to be used that establish the motivation toward safety in an external way, obtaining a knowingly safe worker under external control. There is nothing wrong with this external control toward safety; most of the motivation to perform the job in unsafe ways is due to external motivational control toward unsafe behaviours, normally without the worker or his/her bosses even being particularly aware of it.

6. SOME CONCLUSIONS AND FINAL THOUGHTS

The purpose of prevention is for the people inside the companies –and the companies themselves– to work in safety and health. To achieve this, they must be able to, know how to and want to work safely.

It is very important to realize that the three conditions must be evaluated,because each of them depends on different groups of factors. Moreover, the corresponding intervention techniques that can be applied to a deficit in a condition are specific to that condition. In other words, a problem in the first condition cannot be resolved or replaced with training or motivation. More commonly, a deficit in the third condition cannot be solved with an intervention based on training. Why? Because as everybody knows, training does not serve that purpose. The three conditions are

necessary but none of them is sufficient by itself. The factors and preventative action techniques indicated for each condition are specific and clearly different.

When people don’t work safely in your company, ask yourself: Which of these three conditions of the triconditional model is not being met? And, as a result, look for the appropriate techniques for that condition. Often the problems come from a complex mixture of difficulties in two or more conditions. In this case, it is necessary to look for the best combination and prioritize according to the known principles of preventative action (e.g., Artº 15 LPRL) and the resources.

As the solutions for one condition aren’t effective for another, now it makessense to make an authentic diagnosis. Taking preventative action without an adequate diagnosis is like prescribing medication for a patient without seeing him or her. I hope it has become clear that the old idea “a little bit of medicine can’t hurt” (in risk prevention, for example, “let’s do some training since it always helps and at the same time, it backs us up) may not be the best answer. It may not be effective or efficient.

The European and Spanish legislation on prevention is built on a social base that affirms the legitimate right of the workers to due protection (Artº 14.1 LPRL). This right, the focus and idea behind the Work Risk Prevention Law and its developments, generates the corresponding duty of the companies (Artº 14.2 LPRL). To this perspective, for effective prevention, must be added the duty of all the employees to bring safety to their jobs, for themselves and for others, and the right of companies to count on some legislative, administrative and social conditions that guarantee that they can develop as safe settings. Among other reasons, this is because, given that the risk is shared, the right of each worker to safety cannot be guaranteed without establishing the duty of each and every one of the employees at each and every hierarchical level. This duty, which can be framed within the principle of co- responsibility, exceeds mere obedience to or follow-up of the responsibility of the company. The triconditional model emphasizes this idea of co-responsibility, as the three conditions must be satisfied for each job at each hierarchical level. And this has many implications, for example, the responsibility of management and the unacceptable legal vacuum with regard to their training in prevention.

I have developed this triconditional model over the years as a result of giving numerous conferences and training sessions to prevention technicians and other professionals. The idea is to respond in a simple way, but in a way that helps us to structure our thoughts about the main important questions in prevention: What do we need to achieve safety? How do we achieve safe work and, therefore, reduce or eliminate (if possible and as far as possible) accidents and other damages?

The model intentionally emphasizes that the traditional techniques of safety and hygiene are as necessary as they are insufficient. In addition, it emphasizes intentionally that training is also necessary, but it is not the be all and end all. Moreover, it is definitely not indicated as the main solution for problems that depend on the other two conditions. Although I have been explaining this model for the past fifteen years or so, only recently have I had occasion to write it down. Here I have developed some of the original aspects of the theory, like the emphasis on the diagnostic-intervention connection, the concept of co-responsibility, and the vision of the model as a cycle of continuous improvement.

I hope this vision is compatible with many diverse and necessary contributions from the indispensable multi-disciplinary approach to prevention, and that it provokes reflection and suggestions among the colleagues who work on the sometimes uncomfortable battle line dealing with companies.

Given the comprehensive nature of the model, it is difficult to design a formal contrast outside the laboratory, but I am gathering data and am grateful for critical incidents, anecdotes and testimonies that show the importance of each of the three conditions, in order to perfect and improve these reflections by better linking them to

what occurs when we try to carry out prevention on a day to day basis.

ACKNOWLWDGEMENTS

This paper was developed within the CONSTOOLKIT Project, [BIA2007-61680], which focuses on the development of safety intervention tools for the psychosocial factors related to accidents. Financial support was provided by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (España) and The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF - FEDER).

REFERENCES

Meliá, J. L. (2007). Comportamiento Humano y Seguridad Laboral. Bilbao: Lettera Publicaciones.

Reason, J. (1993). Managing the management risk: New approaches to organizational safety. In Wilpert, B. & Qvale, T. Reliability and safety in hazardous work systems. Pag. 7-22. Hove, Great Britain: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Papers relacionados