Introduction

Stress is a physiological reaction of the body in which various defense mechanisms come into play to tackle a situation that is perceived as threatening or highly demanding. When it is prolonged it can lead to physical and psychological illnesses and it is one of the most significant causes of absence from work in developed countries [1].

Starting specialty medical training is considered by many authors to be a trigger factor for occupational stress to a pathological level (distress) as a result of the numerous changes that occur in the lifestyles of these doctors [2-7].

There are some studies that relate personality profile to occupational stress [8-12] and others that relate it to certain genetic factors [13-20]. Nonetheless, no study has been found up to now in the literature consulted which associates both profiles with occupational stress and in the event of finding such associations, whether there are differences between the sexes.

Our objective is to demonstrate that there is an association between genetic and personality profiles in doctors who begin their specialty medical training and develop occupational stress and to construct a predictive model that determines vulnerability and suggests protection measures against occupational stress in this group prior to beginning residency.

The subsequent objective of this project would be to use said model for the early identification of those resident medical interns who were “vulnerable” to developing occupational stress and to use a prevention programme with them.

Methodology

Sample

The sample consisted of residents who began their specialty training in a tertiary hospital in Madrid. Each year, 124±4 residents join this hospital.

The sample was selected in the initial medical examination and was put together during three consecutive years. In total 168 residents began the study and 136 completed it. This sample was considered to be representative of the residents that begin specialty medical training in this hospital because of the number of participants and the distribution of specialties that the participants in the study had.

The inclusion criteria were: starting residency in the chosen hospital, being deemed satisfactory in the initial medical examination in the Prevention of Occupational Risks Service and voluntarily agreeing to form part of the study by means of informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: being deemed unsatisfactory in the initial medical examination, a diagnosis of occupational stress at the start of the study and residents who did not conclude the study.

Method

This was a nested case control study. The cohort was chosen on the signing of the contract for their first year of residency and was monitored for six months, at which point the cases were detected as opposed to the controls. From this moment the variables selected at the beginning for observing and analysing the differences and magnitude of risk of developing occupational stress were compared.

A case was defined as a resident who developed occupational stress in the sixth month following the start of their residency as a internal medical residents and a control was a resident who did not develop it.

The cases were new, detected from the point when the research began (incident cases) in a very homogeneous population. All the subjects who did not develop occupational stress were included in the study (controls). This gave a ratio of 1:8 for cases and controls, which gave greater statistical benefit (potential).

The period of six months from the start of residency was determined as suitable in this research because it was thought to be sufficient time for the resident medical intern to be immersed in the “start of their first year of residency” and this timescale was backed up by other research studies that have used the same period for development of occupational stress [21, 22].

Tools

To collect basic information a specific protocol was designed that collected the following variables: age, sex, nationality (for which the nationality of both parents was taken into account since in the study genetic analysis would be carried out), marital status, cohabitation and place of residence, distinguishing between urban and rural.

In the professional variables section, the ranking obtained by the internal medical resident in the annual national examinations, the specialty chosen were collected, and the residents were asked whether the chosen specialty was the one they had wanted to choose.

In order to assess personality, the “Big Five” Personality Questionnaire (BFQ), translated and adapted for the Spanish population by J. Bermudez (1995) was used, and Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R), translated and adapted for the Spanish population by Gutiérrez-Zotes et al. (2004).

For the genetic study, the ANKK1 TaqIA polymorphisms were analysed for their two polymorphic alleles A1 (CT or TT) and A2 (CC), the polymorphism Val158 Met, of the COMT gene, that encodes Catechol–O-methyltransferase (COMT) for its three polymorphisms (VM, VV and MM) and the DRD2 polymorphism C957T for its CT, TT and CC alleles, all from the dopaminergic system.

To study the affective variables, Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI E-R), a self-administered inventory designed by Spielberger et al., adapted for the Spanish population by TEA Ediciones (1982), and Depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a self-administered scale developed by Beck (1961) validated and adapted for the Spanish population by Conde and Useros (1975).

To study occupational stress, the Work-Related Strain Inventory (WRSI) validated by Revicki, May and Whitley (1991) for health personnel, translated and validated for Spanish doctors by Mingote (1995) was used. The questionnaire contains 18 questions and a score of 44 or more indicates the presence of pathological stress.

Statistical Method

In order to describe the data at the start of the contract, we used the mean, standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range or with absolute and relative frequencies. To analyse the data represented and compare the cases with the controls, the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, the student’s t test or the Mann Whitney U test were used as appropriate. The affective and occupational stress variables were measured upon the signing of the contract and six months later and the rest of the variables were measured at the beginning of the study.

Regarding the analysis of genetic data, the Hardy-Weinberg principle did not need to be applied since on one hand, the Neuroscience Laboratory of the Institute for Health Research at the hospital in which we carried out the study was validated to implement the genotyping techniques used for this study and on the other hand, the controls employed in this research came from the same sample, which is why they were considered homogeneous in terms of matching the controls in this study.

For the stratified association analysis, bivariate logistic regression was used, quantifying the magnitude of effect by means of the Odds Ratio (OR).

To create the predictive models, multivariate logistic regression was carried out based on the significant variables of the bivariate analysis previously referred to. The predictive models were created for men and women. The multivariate analysis enabled variables with a significance of 5% to be introduced, excluding those with a 10% significance.

Prior to the regression model, a study of relationships between possible independent variables was carried out to avoid problems of multicollinearity in the model. To evaluate the models, goodness of fit was measured using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and discriminatory capacity by the ROC area.

SPSS V.18.0 for Windows was used to process the statistical data.

Limitations of the Study

The number of cases was small. This research was carried out on a population with university education in medicine and who had taken a selection test (MIR), because of which it has to be considered that there may be a bias regarding stress coping skills (greater resources), compared with the general population. We have to include in the limitations of this study the loss of subjects bias and the possibility that the sample was affected by non response or volunteer bias.

Results

Descriptive Analysis of the General Sample

The descriptive results of the socio-demographic variables are shown in Table 1.

|

Age |

25.73 (23-40) 2.48 |

|

|

Sex N (%) |

Men |

43 (31.36) |

|

Women |

93 (68.64) |

|

|

Nationality N (%) |

Spanish |

125 (91.9) |

|

foreign |

11 (8.1) |

|

|

Marital status N (%) |

Single |

128 (94.1) |

|

Married |

8 (5.9) |

|

|

Cohabitation N (%) |

Family of origin |

69 (50.7) |

|

Roommates |

41 (30.1) |

|

|

Own family |

17 (12.5) |

|

|

Alone |

9 (6.7) |

|

|

Place of residence N (%) |

Urban |

134 (98.5) |

|

Rural |

2 (1.5) |

|

Table1. Description of the socio-demographic variables

The descriptive results of the professional variables are shown in Table 2. We would point out that the chosen specialty corresponded to the desired specialty in 81% of cases.

|

Ranking in the national selection test (MIR) median (IQR) |

962 (262-1621.75) |

|

Classification of medical specialty N (%) |

Internal medicine |

75 (55.15) |

|

Surgical |

30 (22.06) |

|

|

Medical-Surgical |

9 (6.62) |

|

|

Diagnostic / Central Services |

22 (16.18) |

|

|

Chosen specialty = desired specialty N (%) |

Yes |

110 (80.88) |

|

No |

26 (19.12) |

|

Table 2: Description of professional variables

Regarding the affective variables, in the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI E-R) all the values obtained were lower than the reference values for the Spanish population of the same age group and sex, with the exception of the Trait Anxiety in men that coincided with the reference values.

All the values obtained for depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were much lower than the point at which it is considered that there is no depression.

The results of the personality variables were quite similar to the Spanish population reference values in the BFQ. In the TCI, the score on the temperament scale for the Reward Dependence factor stood out, since more than 75% of our sample scored higher values than those established as references in the Spanish population. In the character scale, more than 85% of the residents scored higher than the reference value for the Spanish population in relation to Self-directedness.

In relation to the genetic variables, we analysed the ANKK1 gene Taq1A polymorphism. The CC (A2) allele was the most common in men and women and the TT allele was only found on very few occasions in both groups.

Regarding the genotype of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism, the most common allele in men and women was VM.

In the case of the DRD2 C957T polymorphism, the most common allele in men and women was CT.

In relation to the dependent variable in the study, occupational stress measured with the Work-Related Strain Inventory (WRSI), at the beginning of the study, one case exceeded the score considered as the cut-off point and was therefore excluded.

Descriptive and Comparative Analysis at Six Months: Cases and Controls

Occupational stress measured at 6 months from the start of the specialty medical training using the WRSI obtained a mean of 32.63 with a minimum score of 20 and a maximum of 50.

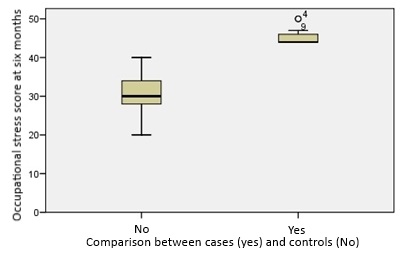

We found that 15 residents (11.03%) exceeded the cut-off point and we classified them as “cases” with a mean of 45.4 and a maximum score of 50. Our “controls” scored a mean of 31.04 and a maximum score of 40 (Graph 1). This represents a Cumulative Incidence (CI) of occupational stress of 11% at 6 months.

Graph1. Comparison of occupational stress between cases and controls

The difference between both groups was significant (p-value < 0.001) and Table 3 sets out the results of the comparison in quartiles.

|

Occupational stress |

P-value |

||||||

|

Yes (cases) (N=15; 11.03%) |

No (controls) (N= 121; 88.97%) |

||||||

|

Work-Related Strain Inventory (WRSI) |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

0.000 |

|

44 |

44 |

46 |

28 |

30 |

34.5 |

||

Table 3. Description and comparison of occupational stress between cases and controls

None of the socio-demographic or professional variables included in the study were significant in the comparison between the residents who presented occupational stress and those who did not.

Both the variable for measuring depression (p-value <0.001) and the variable for measuring anxiety (Trait-Anxiety in men with p-value = 0.031 and in women p-value < 0.001 and State-Anxiety in men with p-value=0.001 and in women p-value <0.001) showed significant differences between the cases and controls.

The comparison of the BFQ or the “Big Five”, showed significant differences with low extraversion (p=0.014) and high neuroticism (p<0.000) in the residents that had occupational stress as against those who did not.

With regard to the Cloninger TCI, the residents with occupational stress presented a profile of pessimism (p-value = 0.028) and shyness (p-value = 0.034) that was significant compared to those who did not have it.

In the study of “candidate genes” for occupational stress (Table 4), regarding Taq1A of the ANKK1 gene, we did not find significant differences between cases and controls nor between the sexes in terms of occupational stress.

Regarding the genotype of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism, we found significant differences in men (p-value= 0.016) between the cases and the controls in relation to the distribution of the three polygenic variants. We did not find any significant difference between the female cases and controls.

With regard to the DRD2 C957T polymorphism, we found significant differences (p-value= 0.036) between the cases and controls in women in terms of the distribution of the three polygenic variants. We did not find any significant differences between the male cases and controls.

|

Occupational stress |

p-value |

|||||||

|

Yes (cases) (N = 15; 11.03%) |

No (controls) (N= 121; 88.97%) |

|||||||

|

Taq1A (N; %) |

Men |

(A2) CC |

3 (50) |

27 (73) |

0.189 |

|||

|

(A1+) |

CT |

2 (33.3) |

9 (24.3) |

|||||

|

TT |

1 (16.7) |

1 (2.7) |

||||||

|

Women |

(A2) CC |

8 (88.9) |

59 (70.2) |

0.587 |

||||

|

(A1+) |

CT |

1 (11.1) |

22 (26.2) |

|||||

|

TT |

0 (0) |

3 (3,6) |

||||||

|

ComtVal158Met (N; %) |

Men |

VV |

4 (66.7) |

7 (18.9) |

0.016 |

|||

|

MM |

2 (33.3) |

13 (35.1) |

||||||

|

MV |

0 (0) |

17 (45.9) |

||||||

|

Women |

VV |

1 (11.1) |

20 (23.3) |

0.360 |

||||

|

MM |

4 (44.4) |

18 (21.4) |

||||||

|

MV |

4 (44.4) |

46 (54.8) |

||||||

|

C957T (N; %) |

Men |

CC |

2 (33.3) |

11 (29.7) |

1.000 |

|||

|

CT |

3 (50) |

17 (45.9) |

||||||

|

TT |

1 (16.7) |

9 (24.3) |

||||||

|

Women |

CC |

6 (66.7) |

24 (28.6) |

0.036 |

||||

|

CT |

3 (33.3) |

35 (41) |

||||||

|

TT |

0 (0) |

25 (29.8) |

||||||

Table 4. Description and comparison of genetic variables by sex in cases and controls.

Association and Risk Analysis Stratified by Sex in Cases and Controls

The same bivariate analysis was carried out with all the independent variables analysed for each sex and we obtained significant results in relation to men. These are described in Table 5, in which the Odds Ratio is represented with its confidence interval of 95%.

|

Confidence Interval95% |

||||

|

Odds Ratio |

p-value |

lower |

upper |

|

|

BFQ- High neuroticism |

9.600 |

0.012 |

1.363 |

67.596 |

|

ComtVal158Met (MM) |

8.571 |

0.026 |

1.300 |

56.525 |

|

STAI-E |

6.400 |

0.033 |

0.999 |

40.998 |

Table 5. Association and risk in male cases and controls.

In the case of women the significant results we obtained are described in Table 6, in which the Odds Ratio is represented with its confidence interval of 95%.

|

Confidence Interval95% |

||||

|

Odds Ratio |

p-value |

lower |

upper |

|

|

Low Sociability (HA3) |

9.86 |

0.006 |

1.904 |

51.104 |

|

BFQ- High neuroticism |

7.46 |

0.011 |

1.435 |

38.737 |

|

BFQ- Low extraversion |

6.58 |

0.025 |

1.270 |

34.079 |

|

BFQ- Low Perseverence |

6.25 |

0.017 |

1.461 |

26.739 |

|

BFQ- Low agreeableness |

4.37 |

0.046 |

1.050 |

18.23 |

|

C957T (CC) |

5.000 |

0.031 |

1.156 |

21.627 |

Table 6. Association and risk in female cases and controls.

Multivariate Analysis in the Models for Men and Women

Based on the significant variables in the bivariate analysis, predictive models for men and women were created with a multivariate analysis of logistic regression.

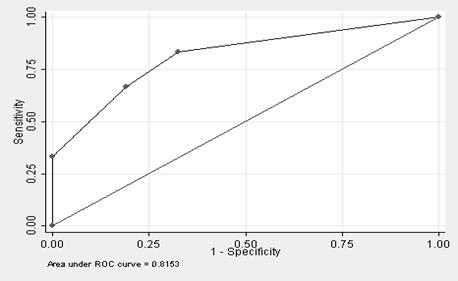

In men, a single predictive model relating genetic and personality variables could not be established, nevertheless it was possible to establish a model that associated greater state anxiety with the low-activity variant of the COMT gene (Met/Met) Val158Met polymorphism. The variable with the greatest magnitude of effect as a risk for developing occupational stress six months after the beginning of residency in this model for men is genetic (OR=14.56), followed by anxiety (OR=12.07). The model is calibrated with a p-value H-L of 0.268 and criterion validity (area under the curve) of 0.868 (Table 7; Graph 2).

|

OCCUPATIONAL STRESS |

Odds Ratio |

p-value |

Confidence Interval95 % |

|

|

lower |

upper |

|||

|

COMTVAL158MET (MM) |

14.562 |

0.026 |

1.373 |

154.458 |

|

STAI- State-Anxiety |

12.07 |

0.045 |

1.055 |

138.175 |

|

p-value Hosmer Lemeshow |

0.341 |

|||

|

Area under ROC curve |

0.815 |

|||

Table 7: Multivariate predictive model for men

Graph 2: Area under the curve for the multivariate predictive model for men

In the case of women, it was feasible to construct a predictive model with personality and genetic variables.

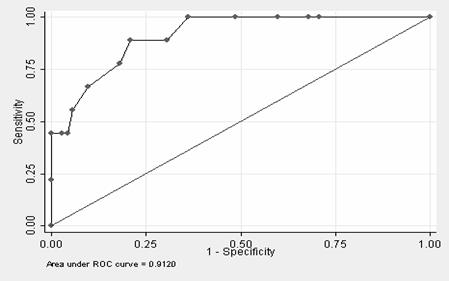

The variable with the greatest magnitude of effect as a risk for developing occupational stress six months after beginning residency in the model are high neuroticism values (OR=17.69), followed by low values of extraversion (OR=11.93), followed by having the CC variant of the DRD2 C957T polymorphism (OR=7.54) and having low values for perseverence (OR = 6.1). This model is calibrated with a p-value H-L of 0.710 and criterion validity (area under the curve) of 0.91 (Table 8; Graph 3).

|

OCCUPATIONAL STRESS |

Odds Ratio |

p-value |

Confidence Interval95 % |

|

|

lower |

upper |

|||

|

inferior |

superior |

|||

|

C957T (CC) |

7.538 |

0.044 |

1.059 |

53.612 |

|

BFQ- High neuroticism |

17.688 |

0.010 |

1.973 |

158.560 |

|

BFQ- Low extraversion |

11.933 |

0.024 |

1.387 |

102.675 |

|

BFQ- Low Perseverence |

6.099 |

0.062 |

0.914 |

40.701 |

|

p-value Hosmer Lemeshow |

0.718 |

|||

|

Area under ROC curve |

0.912 |

|||

Table 8: Multivariate predictive model for women

Graph 3: Area under the curve for the multivariate predictive model for women

Graph 3: Area under the curve for the multivariate predictive model for women

Discussion

Through working with a cohort, it has been possible to diagnose occupational stress starting from a situation in which none of the residents had that condition at the beginning of the study, through to six months after the start of residency when there was a cumulative incidence of 11%.

No studies of cumulative incidence have been found, nevertheless occupational stress prevalence studies at the start of specialty medical residency have been identified, which present a higher percentage of occupational stress. For example Zurroza-Estrada in 2009 [23] found a 50% prevalence of moderate-high stress levels in residents at the beginning of their training. Other authors have mentioned “high” or “very high” prevalence [24].

This discrepancy in the results may be related to the different stress measurement tools used and the occupational stress measurement methodology in the different studies.

This study has demonstrated that there are personality differences between residents who develop occupational stress as opposed to those who do not. Through the “Big Five” (BFQ) it was established that the residents who developed occupational stress six months from beginning residency had a personality profile of low extraversion and high neuroticism. These results agree with those of previous studies [8-10, 25].

On the other hand, according to the Cloninger Inventory (TCI), the residents who had occupational stress after six months were classified as pessimistic and shy, in the “Harm Avoidance” dimension. These results match those of other authors [25-28]. However we have not found a relationship between the Novelty Seeking dimension and stress, as other authors have [30].

Regarding gender, unlike other studies that report higher prevalence of occupational stress in women [31-33]; In our study we have not found significant gender differences in its prevalence and neither have other authors[23, 34-36].

Nonetheless we have found differences in the genetic and personality profiles between men and women who develop occupational stress as opposed to those who do not, so in our study in which we stratified by sex, the personality profile in men that developed occupational stress was only significant in terms of high neuroticism.

In women who developed occupational stress, in addition to high neuroticism, low extraversion, low agreeableness and low perseverence in the “Big Five” and lower social support in the “Harm Avoidance” dimension of the TCI were also significant.

These results match those of Costa et al.[10] that related extraversion and perseverence to resilience and the results of Carver[27], which identified that resilient individuals had lower levels of negation, avoidance and escape behaviours and the work of Ong et al. [28] and Tugade et al. [29], with high dispositional optimism and positive emotionality in resilient individuals.

Although the gender differences in this study are not conclusive [37], others, such as that of Zhang [38], argue the differences between men and women with regard to some complex behaviours such as those relating to business initiative. In that study it is shown that while in men genetics have a far lesser effect than environmental factors, in women heritable personality traits like high values of extraversion and low values of neuroticism condition success in this aspect.

This author found that extraversion and neuroticism influenced the genetic effects on women’s tendencies to become business owners, whilst in men, shared extraversion factors and environmental factors had an influence. It is possible that in men, genetics are less associated with personality factors than in women in the development of occupational stress.

The results of the genetic analysis were stratified by sex following the recommendations of some researchers on some of the polymorphisms of the genes studied [39, 40].

Some previous investigations have shown big gender differences in the genetic influences on life events, social relationships and criminal behavior [41-43], therefore there is a need to examine the possible gender differences in the genetic bases in occupational stress.

Regarding the genetics of behaviour, Bolinskey et al. [44] have found that in men, there is very little genetic influence on desirable events, but in women there is a substantial genetic influence on life events, for example, improvements in financial situation or making new friends [43].

Strong genetic effects have also been found on negative life events in women as opposed to men, such as interpersonal problems, legal and financial difficulties. In addition, it has been found that the difference between estimates of heritability in woman compared to men in relation to these events were large.

Regarding the Val158Met polymorphism of the COMT gene, a significant association with stress has been found as in previous studies and in particular, the fact of having the low activity COMT (Met/Met)[14] genotype, although we only found this difference in men.

The gender differences observed may be explained by the effect of the COMT enzyme for metabolising catecholestrogens in women, according to Sazci et al.[39] or Xie et al. [45], who have found that the effect of the estrogens may inhibit the transcription of the COMT gene, that at the same time could interact with the effects of the Val159Met genotype of the COMT gene.

In the research done by Hoenicka et al. [40], a significant association was shown in men with schizophrenia and the 158Val variant as a risk factor, not the same behaviour as stress, nonetheless they obtained the same results when they assessed women, not finding any association between schizophrenia and the COMT gene variants in women.

Regarding the DRD2 C957T polymorphism, the CC allele appeared as a risk in women for developing occupational stress in our study. No literature relating the C957T genotypes to occupational stress has been found, nonetheless there are studies that find an association between the CC genotype of the DRD2 C957T polymorphism and alcoholic patients [46], alcoholic patients with antisocial personality disorder [47], schizophrenia [48,49], substance abuse [50] and post-traumatic stress disorder [51].

In relation to the polymorphism of the TaqI-A1 allele of the ANKK1 gene, no relationship was found with occupational stress. This differs from results obtained by other authors [52] in which an interaction between the genetic polymorphism and the environment has been shown, focusing on the possible influence of the TaqI-A1 allele on coping with stress, by means of a possible “vulnerability in environmental interaction in the presence of stress” and its relationship with associated temperament traits such as harm avoidance.

Regarding the predictive models, in was not possible to establish a predictive model for men that related personality and genetic variables, nonetheless it was possible to establish one with the low activity COMT (Met/Met) genotype and state anxiety.

In the case of women, it was possible to establish a very compact model between the personality variables of the “Big Five” factors (BFQ), with low extraversion, high neuroticism and low perseverence with the CC variant of the DRD2 polymorphism C957T.

The results of this study demonstrate that although the final result is the same (occupational stress), the internal functioning of men and women is different with regard to some variables of personality and in terms of genetics, both in relation to occupational stress, in residents who start their specialty medical training in the hospital where this studied was carried out.

On one hand, in men, it could be that the “gene-environment interaction” predominantly acts in the development of occupational stress while in women it is the “gene-gene interaction” that influences the development of occupational stress. Due to these results, it is worth environmental factors being included as variables in future studies on stress, as well as analysing men and woman separately.

On the other hand, the results of this research conclude by associating the DRD2 C957T homozygous polymorphism CC with the development of occupational stress in women. This result opens new lines of investigation, since firstly this polymorphism had not been related to occupational stress and secondly, gender-related differences had not been observed in its behaviour.

Conclusions

Occupational stress was identified in residents who began their specialty medical training, with a cumulative incidence of 11% after six months.

The difference between the personality and genetic profiles of the residents who had occupational stress (cases) and those of the residents who did not (controls) were stratified by sex.

In men it was not possible to establish a predictive model of vulnerability/protection that related personality and genetic variables to the development of occupational stress, nevertheless one could be created, with the low-activity variant of COMT (Met/Met) with the “state anxiety” variable, both variables showing a very strong association with stress (they multiply the likelihood of developing stress by twelve and fourteen). The model has an area under the curve of 0.81, which is a value that shows very good discriminative capacity between those who are going to suffer from stress or not and therefore has very good predictive value.

In women it was feasible to construct a very compact predictive model with personality and genetic variables, formed by “high neuroticism”, “low extraversion”, “low perseverence” and the CC variant of the DRD2 C957T polymorphism. This model has an area under the curve of 0.91 and therefore has excellent predictive value.

Acknowledgement

A preliminar versión of this paper was presented in the Congress ORP’conference 2014.

References

- 1. European Agency for Health and safety at Work. OSHA. Estrés Laboral y Evaluación de Riesgos 2009; 54.

- 2. Revicki D, Whitley T, Gallery, M. Organizational characteristics, perceived work stress, and depression in emergency medicine residents. Behavioral Medicine. 1993; 19 (2): 7481.

- 3. Morales P, LópezIbor J. Stress and adjustment at the beginning of postgraduate medical training. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines.1995; 23(5): 241248.

- 4. Gardiner M, Lovell G, Williamson P. Physician you can heal yourself! Cognitive behavioural training reduces stress in GPs. Fam Pract. 2004; 21 (5): 54551.

- 5. Buddeberg Fisher B, Klaghofer R., Buddeberg, C. Stress at work and wellbeing in junior residents. Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005; 51(2): 16378.

- 6. Buddeberg Fisher B, Klaghofer R, Stamm M, Siegrist J, Buddeberg C. Work stress and reduced health in young physicians: prospective evidence from Swiss residents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health.2008; 82 (1): 3138.

- 7. Zurroza Estrada A, Oviedo Rodríguez I, Ortega Gómez R. Relación entre rasgos de personalidad y el nivel de estrés en los médicos residentes. Revista de Investigación Clínica.2009; 61 (2): 110118.

- 8. Bienvenu O, Stein M. Personality and anxiety disorders: a review. J Pers Disord. 2003; 2 (17): 13951.

- 9. Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSMIV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998; 107 (2): 17992.

- 10. Costa P, McCrae R. Normal Personality Assesment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessmen. 1992; 4 (1): 513.

- 11. BuydensBranchey L, Branchey M, Hudson J, Dorota Majewska M. Perturbations of plasma cortisol and DHEAS following discontinuation of cocaine use in cocaine addicts. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002; 27(12): 8397.

- 12. Alim T, Feder A, Graves R, Wang Y, Weaver J, Westphal M, et al. Trauma, resilience, and recovery in a highrisk AfricanAmerican population. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165 (12): 15661575.

- 13. Pezawas L, MeyerLindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, et al. 5HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulateamygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nature Neurosci. 2005; 8 (6): 828834.

- 14. Heinz A, Smolka M. The effects of catechol Omethyltransferase genotype on brain activation elicited by affective stimuli and cognitive tasks. Rev. Neurosci. 2006; 17 (3): 359367.

- 15. Malhotra A, Kestler L, Mazzanti C, Bates J, Goldberg T, Goldman D. A functional polymorphism in the COMT gene and performance on a test of prefrontal cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159 (4): 6524.

- 16. Zubieta J, Heitzeg M, Smith Y, Bueller J, Xu K, Xu, Y, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects muopioid neurotransmitter responses to pain stressor. Science. 2003; 299 (5610): 12403.

- 17. Winterer G, Goldman, D. Genetics of human prefrontal function. Brain Reserach Reviews. 2003; 43 (1): 13463.

- 18. Bau C, Almeida S, Hutz M. The TaqI A1 allele of the dopamine D2 receptor gene and alcoholism in Brazil: association and interaction with stress and harm avoidance on severity prediction. Am J Med Genet. 2000; 96 (3): 302306.

- 19. Zhou Z, Zhu G, Hariri AR, Enoch MA, Scott D, Sinha R, et al. Genetic variation in human NPY expression affects stress response and emotion. Nature.2008; 452 (7190): 9971001.

- 20. Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, et al. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxietyrelated behavior. Science. 2006; 314 (5796): 140143.

- 21. Whitley TW, Allison EJ Jr, Gallery ME, Heyworth J,Cockington RA,Gaudry P, et al. Workrelated stress and depression among physicians pursuing postgraduate training in emergency medicine: An international study. Ann Emerg Med. 1991; 20 (9):992996.

- 22. Revicki D, Gershon R. Workrelated stress and psychological distress in emergency medical technicians. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996; 1 (4), 391396.

- 23. Zurroza Estrada A, Oviedo Rodríguez I, Ortega Gómez R. Relación entre rasgos de personalidad y el nivel de estrés en los médicos residentes. Revista de Investigación Clínica. 2009; 61 (2), 110118.

- 24. Pino Morales S, López Ibor A. Stress and adjustment at the beginning of postgraduate medical training. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1995; 23 (5): 241248.

- 25. Matthews G, Gilliland K. The personality theories of H.J. Eysenck and J.A. Gray: A comparative review. Personality and Individual Difference.1999; 26 (4): 583–626.

- 26. Carver, CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med.1997; 4 (1): 92100.

- 27. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broadenandbuild theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001; 56 (3): 218226.

- 28. Ong A, Bergeman C, Bisconti T, Wallace K. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psycho. 2006; 91:730749.

- 29. Tugade M, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004; 86 (2): 320333.

- 30. Noble E, Ozkaragoz T, Ritchie T, Zhang X, Belin T, Sparkes R. D2 and D4 Dopamine Receptor Polymorphisms and Personality. American Journal of Medical Genetics.1998; 81:257267.

- 31. Carlson G, Miller D. Suicide, affective disorders and women physicians. Am J Psychiatry. 1981; 138:13301334.

- 32. FirthCozens J. Emotional distress in junior house officers. BMJ. 1987; 295 (6597): 533536.

- 33. Arenas Osuna J. Estrés en médicos residentes en una Unidad de Atención Médica de tercer nivel. Cirujano General.2006; 28 (2): 103109.

- 34. Granada Jiménez O, Morales Socorro M, LópezIbor Aliño J. Psicopatología y factores de riesgo durante la residencia. 2010. Actas Esp Psiquiatr; 38 (2): 6571.

- 35. Whitley TW, Gallery ME, Allison E J Jr Factors associated with stress among emergency medicine residents. Annals of emergency Medicine. 1989; 18 (11), 115761.

- 36. Whitley TW, Allison E J Jr, Gallery ME et al. Workrelated stress and depression among physicians pursuing postgraduate training in emergency medicine: An international study. 1991. Ann Emerg Med; 20: 992996.

- 37. Judge T, Remus I, Zhang Z. Genetic influences on core selfevaluations, job satisfaction, and work stress: A behavioral genetics mediated model. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes. 2012; 117 (1): 208220.

- 38. Zhang Z, Zyphur M., Narayanan J, Arvey R, Chaturvedi S, Avolio B, et al. The genetic basis of entrepreneurship: Effects of gender and personality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2009; 110: 93107.

- 39. Sazci A, Ergul E, Kucukali G, Kilic G, Kaya G, Kara I. CatecholOmethyltransferase gene Val108/158Met polymorphism, and susceptibility to schizophrenia: association is more significant in women. Brain Res.Mol. 2004; 132 (1): 5156.

- 40. Hoenicka J, Garrido E, Ponce G, RodriguezJiménez R, Martínez I, Rubio G, et al. Sexually Dimorphic Interaction Between the DRD1 and COMT Genes in Schizophrenia. American J. Of Medical Genetics. 2009; 153B (4): 948954.

- 41. Eley TC, Lichtenstein P, Stevenson J. Sex difference in the etiology of agressive and nonagressive antisicial behavior: results two twin studies. Child Development. 1999; 70 (1): 155168.

- 42. Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL. Social relationships, stressfil life events, and selfreported physical health: Genetic and enviromental influences. Phychology and Health. 1995; 10 (4): 295319.

- 43. Saudino K J, Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, McClearn GE, Plomin R. Can personality explain genetic influences on life events? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997; 72(1): 196–206.

- 44. Bolinskey PK, Neale MC, Jacobson KC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Sources of individual differences in stressful life event exposure in male and female twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2004; 7 (1): 33–38.

- 45. Xie T, Ho S, Ramsden D. Characterization and implications of estrogenic downregulation of human catecholOmethyltransferase gene transcription. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999; 56 (1): 3138.

- 46. Ponce G, JiménezArriero MA, Rubio G, Hoenicka J, Ampuero I, Ramos J., et al. TaqI A Polymorphism In DRD2 And Antisocial Personality Disorder In A Sample Of Alcoholic Spanish Men. The European Journal of Psychiatry. 2003; 18 (7):35660.

- 47. Ponce G, Hoenicka J, JiménezArriero MA, RodríguezJiménez R, Aragüés M, MartínSuñé N et al. DRD2 and ANKK1 genotype in alcoholdependent patients with psychopathic traits: association and interaction study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 193 (2): 121125.

- 48. Lawford B, Young R, Swagell C, Barnes M, Burton S, Ward W, et al. The CC genotype of the C957T polymorphism of the dopamine D2 receptor is associated with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005; 73: 3137.

- 49. Hoenicka J, Aragues M, RodriguezJimenez R, Ponce G, Martinez I, Rubio G, et al C957T DRD2 polymorphism is associated with schizophrenia in Spanish patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 114 (6): 435438.

- 50. Perkins K, Lerman C, Grottenthaler A, Ciccocioppo M, Milanak M, Conklin C, et al. Dopamine and opioid gene variants are associated with increased smoking reward and reinforcement owing to negative mood. Behav Pharmacol.2008; 19 (56): 641649.

- 51. Voisey J, Swagell C, Hughes I, Morris C, Van Daal A, Noble E, et al. The DRD2 gene 957C>T polymorphism is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in war veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2009; 26 (1): 2833.

- 52. Bau C, Almeida S, Hutz M. The TaqI A1 allele of the dopamine D2 receptor gene and alcoholism in Brazil: association and interaction with stress and harm avoidance on severity prediction. Am J Med Genet. 2000; 96 (3): 302306.

Papers relacionados