Introduction

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs) are a major occupational concern in the relationships between work and disease [1-3]. Over the past few years there has been an increasing interest on studying the associations between work and MSDs (musculoskeletal disorders).

WRMSDs are a large group of medical conditions that affect the musculoskeletal system which include, among others, diseases of the muscles, tendons, nerves, and also joint injuries [4].

Nurses WRMSDs could be divided into two major groups related to: (i) patient lifting and mobilization, mainly with low back physical demands and (ii) patient treatment that includes the performance of static or repetitive tasks, with or without application of force.

Nurses are considered the health care professional group more often affected by WRMSDs, mainly low-back pain (LBP) [2]. Actually nursing involves heavy physical work tasks such as lifting and transferring patients, which require sudden movements, most of the time in non-neutral postures (mostly awkward postures), working in organizational strain, and operating hazardous equipment [5].

The etiology of WRMSDs is multifactorial [6, 7] and many studies conducted in nurses have found associations between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and: i) poor posture (including awkward and static postures) [8]; ii) lifting patients and other manual handling [9, 10]; iii) transferring patients out of bed [11, 12]; iv) work-related stress [13]; v) organizational factors, like reduction of nursing staff [14]; and also vi) some intrinsic or individual factors [15].

The most frequent reported complains associated with nursing demands are on the back, neck and shoulders [16-18].

In occupational medicine it is generally assumed that perceived muscular discomfort and/or pain may be an early sign of musculoskeletal disorders [19, 20] relevant for WRMSDs risk assessment [21].

Studies focused on the relations between nursing work demands and WRMSDs symptoms expose differences in each ward, hospital, and among different countries [1-5, 22, 23].

The present study aimed to identify and analyze the prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in Portuguese hospital nurses and its association with different nursing tasks as well as different job demands involved in these tasks.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional national wide study that targeted all 62.566 Registered Nurses (RN) at the Portuguese Nursing Council (PNC) with 26.920 (43%) of them working in hospitals.

Portuguese nurses were invited to participate in this self-report WRMSDs symptoms questionnaire used as the survey instrument. The request was made at the Portuguese Nursing Council (PNC) website and it was available online on the Survey Monkey Platform between June 2010 and February 2011.

Questionnaire has been adapted from the Nordic Questionnaire on Musculoskeletal disorders (NMQ - Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire) previously validated and accepted as a survey instrument [24, 25] and already used in Portugal [4, 26, 27]. It is mainly divided in four sections intended to characterize: (i) demographic profile such as age, gender, weight and height; (ii) the presence or absence of musculoskeletal symptoms in nine anatomical sites in the past 12 months and in the past 7 days; (iii) details on the respondent’s job, physical demands, and its relationship with symptoms, such as information about work status, work setting, years of practice and nursing activities and (iv) general health status. Body segments evaluated includes trunk (cervical, dorsal and low back), upper limbs (shoulders, elbows and wrist/hand) and lower limbs (thighs, knees and ankles/feet).

Statistical analysis was performed using the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version PASW Statistics 21.

To determine the increased likelihood of having WRMSDS symptoms in the past 12 months was estimated the Odds Ratio and the respective 95% confidence interval through the method of Logistic Regression: Forward LR. A level of significance of 5% was set for all statistical tests.

The Chi-square Test of Independence was used to evaluate if the prevalence of low-back symptoms depends on gender, age, Body Mass Index (BMI) and nurses professional category.

Results

A total of 2.140 registered nurses answered the questionnaire (3.42% of all Portuguese registered nurses) being 1.396 of them hospital nurses which, accordingly to the Portuguese Nursing Council (2010), represent up to 5.19% of all nationwide hospital nurses (n=26.920).

The sample was quite largely female (75.8%), having averages figures for age (37.2 years); weight (67.02 kg), and height (1.65 m).

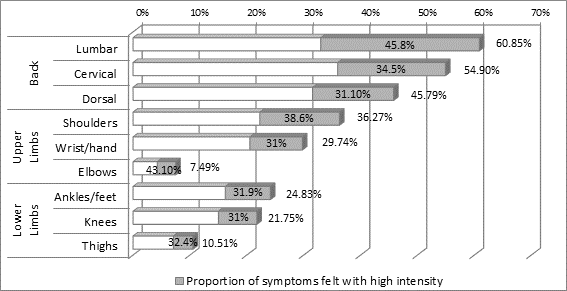

Findings clearly showed a high frequency of musculoskeletal symptoms in the last 12 months in hospital nurses (Figure 1).

The most prevalent complain was in the Lumbar region (60.85%). Among the 1.396 hospital nurses, 69.6% referred to work night-shifts, and 88% reported to have more than 1 musculoskeletal symptom.

Figure 1 – Prevalence of WRMDs symptoms in the last 12 months in hospital nurses and proportion for each of these felt with high intensity.

Other relevant aspects were reported, like symptoms intensity: about 19% of the total sample says that feel one or more WRMSDs with high intensity. Low back symptoms were also the worst intensity-wise self-reported symptoms (45.8%). In what concerns about WRMDs frequency, 33% of all nurses’ affirm to feel pain more than 6 times per year.

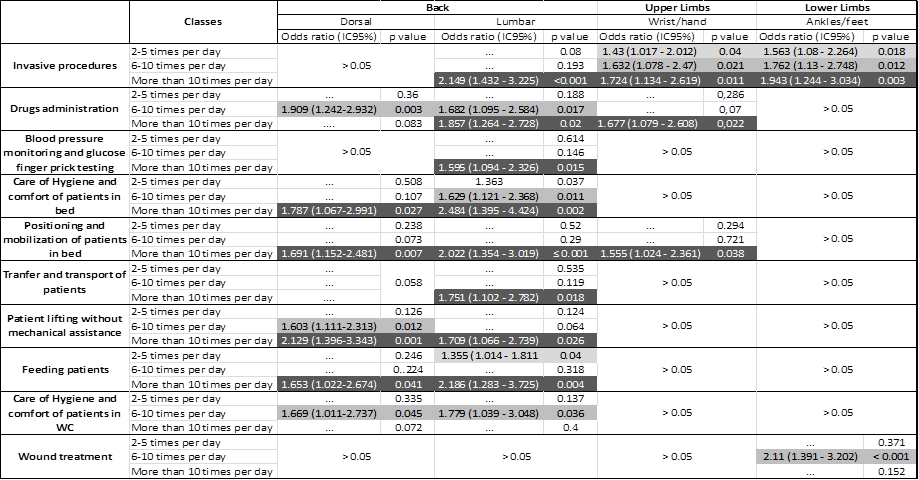

Studied work tasks had no significant effect on the increased likelihood of having shoulders, elbows, cervical, thighs and knees musculoskeletal symptoms.

Nevertheless, there were tasks increasing the probability of having WRMSDs symptoms in upper back, low back, wrist/hands and in ankles/feet areas. These effects were more evident when those tasks were performed more than 10 times a day, highlighting the importance of the frequency of such symptoms (Figure 2).

Tasks performed more than 10 times a day, such as invasive procedures (Odds Ratio = 2.142); care of hygiene and patient comfort in bed (Odds Ratio = 2.484); patient mobilization in bed (Odds Ratio = 2.022); and patient feeding (Odds Ratio = 2.186) had an effect on Dorsal and Low Back Pain (p<0.05).

Invasive procedures were the only working task producing simultaneously effects on lumbar, dorsal, wrist/hand and ankles/feet musculoskeletal symptoms.

Low back pain (LBP) was the most common symptom and was associated with a greater number of working tasks. Analyzing the relationships of individual (age, body mass index (BMI), gender) and job factors (professional category) with the Chi-square Test of Independence it was revealed that low back pain was independent of gender (χ2=2.37, p=0.123), age (χ2=3.86, p=0.27) and BMI (χ2=1.663, p=0.197), but was dependent of job category (χ2=18.86, p=0.001). Individuals with a professional category of "nurses" and "graduate nurses" had a higher prevalence of low back pain (23.44% and 22.88% respectively), and professionals with a category of "nurse-specialists", "chief nurse" and "nurse supervisors" had a lower prevalence (9.42%, 4.86% and 0.37% respectively).

Reference category: 0-1 times per day

Figure 2 – Results from Logistic Regression to quantify nursing tasks effects on the presence of musculoskeletal symptoms in hospital nurses. The squares with “>0.05” means that was not found any significant association.

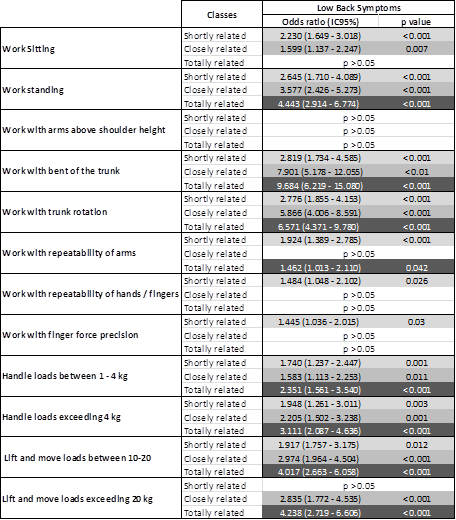

The increased probability of having low back symptoms was analyzed furthermore depending on the nurses self-reported associations between WRMSDS symptoms in the past 12 months and some of their workplaces physical demands such as: sitting work, standing work; working with the arms above the shoulder height; working with the trunk bent; working with trunk rotations; working repeatability with the arms; work repeatability with the hands/fingers; working with finger force precision; handling loads between 1-4kg; handling loads exceeding 4kg; lifting and moving loads between 10-20kg; and lifting and moving loads exceeding 20kg. Self-reported associations between symptoms and these workplaces demands were measured with a 4 items scale: unrelated, shortly related, closely related and totally related. The results showed some working demands considered totally related to WRMSDs symptoms (when compared to the unrelated ones) increasing the probability of suffering from low back symptoms. The physical demands more associated with low back symptoms were working with the trunk bent (Odds ratio = 9.684); working with trunk rotations (Odds ratio = 6.571); standing work (Odds ratio = 4.443); lifting and moving loads exceeding 20kg (Odds ratio = 4.238); and lifting and moving loads between 10-20kg (Odds ratio = 4.017) (Figure 3).

Reference category: Unrelated

Figure 3 – Results from Logistic Regression to quantify the increased probability of having low back symptoms depending on the auto-reported relationship between WRMSDs symptoms and some work demands. The squares with “>0.05” means that was not found any significant association.

Discussion

Findings clearly showed, similarly to other previous studies [4, 5, 18, 23, 28], a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in the last 12 months (cervical = 48.5%; dorsal = 45.9%; lumbar = 60.85%; shoulder = 36.27%; elbows = 7.49%; wrist/hands = 29.74%; hips/thighs = 19.51%; knees = 21.75%; ankles/feet = 24.83%). Low back symptoms were the most frequent and worst intensity-wise self-reported symptoms.

These findings were also similar to other previous studies, where low back pain was described as a very frequent occupational problem in hospital nurses with prevalence ranging between 40% and 60% [3, 5, 22, 29-31].

Results suggest that musculoskeletal symptoms in upper back, low back, wrist/hand and in ankles/feet body regions were associated to specific nursing working tasks, which probably means they could be prevented with the implementation of adequate risk management measures.

These associations were more evident when those tasks were performed more than 10 times a day, highlighting the importance of the frequency in which tasks are performed for the presence of such symptoms. The most prevalent musculoskeletal symptoms were low back and upper back symptoms, and the less affected symptoms were those from the wrist/hand and ankles/feet areas.

Working tasks had no significant effect on the increased likelihood of having shoulders, elbows, cervical, thighs and knees musculoskeletal symptoms. These results suggest that those working tasks seemed not to play an important role for the presence of those symptoms, perhaps being much more influenced by other work occupational hazards, like work-related stressors, organizational factors and some individual factors, like age, gender or BMI [13-15].

Neck symptoms have been described in literature as frequent WRMSDs’ symptoms in nurses [32], and this was confirmed in the present study. However, it was not identified any significant effect of working tasks on these symptoms. Further research must be developed in order to identify other possible risk factors, or confounding factors, that possibly didn’t allowed identifying here relations between neck symptoms and working tasks.

Invasive procedures were just the only working task producing simultaneously effects on all lumbar, dorsal, wrist/hand and ankles/feet musculoskeletal symptoms. Perhaps this could be explained by specific task characteristics which could involve demanding procedures for all body segments and, on the other hand, because it may involve some occupational stressors’ exposure.

Occupational physical demands, considered totally related to WRMSDS symptoms (compared to unrelated ones), increasing the probability of having low back symptoms were working with the trunk bent and working with trunk rotations. These seems to be the work postures more often involved in the performance of the working tasks with a higher effect on the occurrence of low back pain, such as the invasive procedures, hygiene care and comforting patients in bed, feeding patients, and patient positioning and mobilization in bed. Those postures should be better studied.

Conclusions

This study allowed to conclude that some occupational aspects such as nurses’ professional category and nurses’ specific working tasks and it’s demanding postures are the most important organizational risk factors for the commonly prevalent nurses’ musculoskeletal symptoms (low-back symptoms), unlike individual factors such as the age, gender, BMI which were not associated with low-back pain. Therefore, investigation should be focused especially on interventions aimed at preventing these WRMSDs and safeguard nurses’ occupational health and safety acting on those specific working tasks.

Nurses’ musculoskeletal disorders are most of times preventable and intervention in work process, in work equipment’s and in organizational factors must be encouraged. This study highlights the high prevalence of WRMSDs symptoms in Portuguese registered nurses and the need for the development of occupational prevention programs, particularly in hospitals. Occupational Health and Safety are important for healthcare professionals but also for patient safety.

The current study, in addition to identify musculoskeletal symptoms and their related occupational hazards, illustrates the need of a better knowledge about these interactions. That knowledge will contribute for better design of occupational risk management programs concerning WRMSD’s prevention, namely occupational low back pain.

References

1. Ando, S., et al.; Associations of self estimated workloads with musculoskeletal symptoms among hospital nurses. Occup Environ Med, 2000. 57(3): p. 211-6.

2. Trinkoff, A.M., B. Brady, and K. Nielsen; Workplace prevention and musculoskeletal injuries in nurses. J Nurs Adm, 2003. 33(3): p. 153-8.

3. Smith, D.R., et al.; A detailed analysis of musculoskeletal disorder risk factors among Japanese nurses. Journal of safety research, 2006. 37(2): p. 195-200.

4. Fonseca, R. and F. Serranheira; Sintomatologia músculo-esquelética auto-referida por enfermeiros em meio hospitalar. Rev Port Saúde Pública, 2006. Volume Temático: p. 37-44.

5. Kee, D. and S.R. Seo; Musculoskeletal disorders among nursing personnel in Korea. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 2007. 37(3): p. 207-212.

6. Ariëns, G., et al.; Are neck flexion, neck rotation, and sitting at work risk factors for neck pain? Results of a prospective cohort study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2001. 58(3): p. 200-207.

7. Larsson, B., K. Sogaard, and L. Rosendal; Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 2007. 21(3): p. 447-63.

8. Engels, J.A., et al.; Work related risk factors for musculoskeletal complaints in the nursing profession: results of a questionnaire survey. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 1996. 53(9): p. 636-641.

9. Smedley, J., et al.; Manual handling activities and risk of low back pain in nurses. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 1995. 52(3): p. 160-163.

10. bing Yip, Y.; A study of work stress, patient handling activities and the risk of low back pain among nurses in Hong Kong. Journal of advanced nursing, 2001. 36(6): p. 794-804.

11. Pheasant, S. and D. Stubbs; Back pain in nurses: epidemiology and risk assessment. Applied Ergonomics, 1992. 23(4): p. 226-232.

12. Hignett, S.; Work-related back pain in nurses. J Adv Nurs, 1996. 23(6): p. 1238-46.

13. Estryn-Behar, M., et al.; Stress at work and mental health status among female hospital workers. British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 1990. 47(1): p. 20-28.

14. Camerino, D., et al.; Work-related factors and violence among nursing staff in the European NEXT study: a longitudinal cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2008. 45(1): p. 35-50.

15. Lagerström, M., et al.; Occupational and individual factors related to musculoskeletal symptoms in five body regions among Swedish nursing personnel. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 1996. 68(1): p. 27-35.

16. Feyer, A.-M., et al.; The role of physical and psychological factors in occupational low back pain: a prospective cohort study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2000. 57(2): p. 116-120.

17. Gonge, H., L.D. Jensen, and J.P. Bonde; Do psychosocial strain and physical exertion predict onset of low-back pain among nursing aides? Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 2001: p. 388-394.

18. Alexopoulos, E.C., A. Burdorf, and A. Kalokerinou; Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders among nursing personnel in Greek hospitals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2003. 76(4): p. 289-294.

19. Wahlstrom, J.; Ergonomics, musculoskeletal disorders and computer work. Occup Med (Lond), 2005. 55(3): p. 168-76.

20. Hamberg-van Reenen, H.H., et al.; Does musculoskeletal discomfort at work predict future musculoskeletal pain? Ergonomics, 2008. 51(5): p. 637-48.

21. Genaidy, A., E. Delgado, and T. Bustos; Active microbreak effects on musculoskeletal comfort ratings in meatpacking plants. Ergonomics, 1995. 38(2): p. 326-336.

22. Alexopoulos, E.C., A. Burdorf, and A. Kalokerinou; A comparative analysis on musculoskeletal disorders between Greek and Dutch nursing personnel. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 2006. 79(1): p. 82-88.

23. Serranheira, F., et al.; Nurses’ working tasks and MSDs back symptoms: results from a national survey. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation, 2012. 41: p. 2449-2451.

24. Kuorinka, I., et al.; Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon, 1987. 18(3): p. 233-237.

25. Warming, S., et al.; Musculoskeletal complaints among nurses related to patient handling tasks and psychosocial factors--based on logbook registrations. Appl Ergon, 2009. 40(4): p. 569-76.

26. Serranheira, F., et al.; Auto-referência de sintomas de lesões músculo-esqueléticas ligadas ao trabalho (LMELT) numa grande empresa em Portugal. Rev Port Saúde Pública, 2003. 2: p. 37-48.

27. Serranheira, F., A. Uva, and F. Lopes; Lesões músculo-esqueléticas e trabalho: alguns métodos de avaliação do risco. C. Avulso. Vol. 5. 2008, Lisboa: Sociedade Portuguesa de Medicina do Trabalho.

28. Jensen, C., et al.; Work-related psychosocial, physical and individual factors associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in computer users. Work & Stress, 2002. 16(2): p. 107-120.

29. Lorusso, A., S. Bruno, and N. L'Abbate; A review of low back pain and musculoskeletal disorders among Italian nursing personnel. Industrial health, 2007. 45(5): p. 637-644.

30. Tinubu, B.M., et al.; Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in Ibadan, South-west Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2010. 11: p. 12.

31. Holtermann, A., et al.; Patient handling and risk for developing persistent low-back pain among female healthcare workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 2012.

32. Parot-Schinkel, E., et al.; Prevalence of multisite musculoskeletal symptoms: a French cross-sectional working population-based study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2012. 13(1): p. 122.

Papers relacionados