Swuste, Paul HJJ PhD.

Member temporary research committee asbestos, Hof van Twente, Safety Science Group, Delft University of Technology

Jaffalaan 5, Postbox 5015 2600 GA Delft, The Netherlands,

p: 31 15 278 3820, e: p.h.j.j.swuste@tbm.tudelft.nl

Biesheuvel, Pieter-Jan

Chairman temporary research committee asbestos, Hof van Twente

Buurmeijer, Flip

Member temporary research committee asbestos, Hof van Twente

Burdorf, Lex PhD

University Medical Centre Rotterdam, Erasmus University R’dam

Dahhan, Mohssine MSc

University Medical Centre Rotterdam, Erasmus University R’dam

ABSTRACT

Objectives

Extensive asbestos soil pollution was recently observed in the new housing estate in The Netherlands ‘De Hogenkamp’ of the former council of ‘Goor’, presently the ‘Hof van Twente’. Under the authority of the council an independent and temporary research committee conducted a survey of the size of the asbestos problems within the councils’ territory, of the decision making process of the council related to the new housing estate as well as the councils’ future policy related to asbestos. The Eternit factory has its seat in the council and until 1993 the company was one of the biggest primary asbestos industries in the Netherlands.

Results

At least in the period 1937-1974, and probably for a longer period, a very substantial amount of asbestos waste of the Eternit factory has been made available free of charge to citizens and to the council and has been used to pave country roads, paths, and farm yards. The minimal scale of this waste stream was estimated to be 360-4.400 tons of asbestos. This pollution has resulted in a measurable asbestos emission in Goor of 10-100 fibres/l.

The council of ‘Goor’ has and had insufficient knowledge of the ample attention to asbestos related hazards and risks in the national media. The perception of the risks has been strongly influenced by Eternit and by the employment the company offered the council. The council lacked an adequate risk management approach, so the commotion in the media on the asbestos pollution in ‘De Hogenkamp’ came as a complete surprise to administrators, civil servants, and citizens.

Conclusions

The asbestos pollution in the council ‘Hof van Twente is very substantial. There is a great similarity with the Italian city of Casale Monferrato, where an environmental exposure to asbestos created an increased incidence to mesothelioma.

INTRODUCTION

From 1930 onwards the consequences of occupational exposure to asbestos were described extensively in Dutch literature (e.g. Swuste et al, 1988; Burdorf et al, 1991). Recently a prediction of the pleural mesothelioma mortality in The Netherlands was conducted (Segura et al, 2003). This study predicted a peak of 490 pleural mesothelioma amongst men in 2017, with a total death toll from pleural mesothelioma close to 12.400 cases during 2000-2028. The consequences of exposure to asbestos have been spread over a great variety of occupations and branches of industry (Dahhan et al, 2003). Among women the total death toll from pleural mesothelioma remained low, around 800 cases, for the period under study. This probably reflects the low participation of women to occupations with an asbestos exposure. Therefore mesothelioma among women can be regarded as a possible sign of an environmental exposure to asbestos.

Only a few international studies discuss the occurrence of mesothelioma, due to environmental sources, and the classical studies are those conducted in London’s East End, Hamburg, and to the natural occurrence of asbestiform pollution in Turkey (Newhouse en Tompson, 1965; Dalquen, 1970; Bohling en Hain, 1973; Baris ea, 1978). The sources of exposure in Hamburg and London were asbestos contaminated working cloths of asbestos workers, and the direct vicinity of an asbestos industry. Besides family members and housemates of asbestos workers, the population at risk also includes neighbours living within a 1-2 km radium from the asbestos factory.

The importance of non-occupational exposure was recently confirmed in a couple of studies. In the Italian town of Casale Monferrato a high incidence of mesothelioma was found amongst women of Eternit workers (Magnani et al, 1993). A later survey in the same town showed very high mesothelioma mortality rates amongst citizens living till 2 km from the factory (Magnani et al, 2000, 2001; Bourdès et al, 2000). Exposure measurements in Casale Monferrato came up with levels of 50 fibres/l air, which is a factor ten higher than the centre of urban areas (Bourdès et al, 2000).

The council of Goor, presently the ‘Hof van Twente’ is one of the Dutch councils with a sizable asbestos industry within its borders. Towards the end of 2002 the council was startled by the announcement of an asbestos pollution in the new housing estate ‘De Hogenkamp’. This announcement came as a complete surprise for both administrators and public servants of the town. The topic did not only draw attention of regional newspapers, but also of national media.

The community council decided to install an independent temporary research committee (Nov 2002-May 2003), which focussed on the research questions below (Biesheuvel et al, 2003):

- 1. What is the nature, size and seriousness of the asbestos pollution in and around the council ‘Hof van Twente’?

- 2. Can the soil pollution of asbestos be explained from the administrative and official preparation of the new housing estate?

- 3. How should an integral policy regarding asbestos soil pollution be given shape?

METHODS

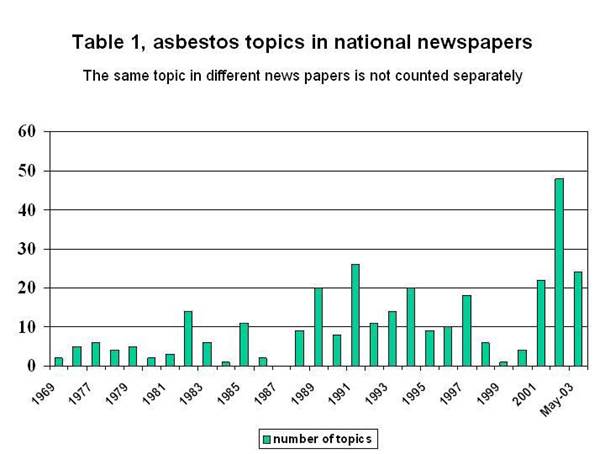

To answer the first question a survey was conducted to the size of the waste stream on asbestos cement, to emission data on asbestos pollution, and to the occurrence of non-occupational asbestos related diseases in the area around the town of Hof van Twente. For the second question an extensive research on official documents was carried out, together with in-depth interviews amongst eight administrators and ten public servants. The final source of information was an overview of national newspaper topics on asbestos related problems from 1969

onward. This source provides insight in the national discussion on the hazards of asbestos, and can be seen as an easy assessable source of information. The overview is part of the media archive of the Safety Science Group of the Delft University of Technology.

The extend the council applied a risk management approach gave answer to the third research question. The different scenarios are the starting point of such anapproach. These scenarios must be defined and appropriate measures have to beinstalled to prevent mitigation of these scenarios. The scenario for the council Hof van Twente can be describes as: ‘Sources of asbestos pollution will lead to an air born emission of asbestos. This emission leads to exposure en enhances the chance of an asbestos related disease’. Depending on the source, this scenario can be divided into different subscenarios.

RESULTS

Asbestos cement waste stream

Each Friday asbestos cement waste was distributed free of charge to a large number of citizens and farmers from the area. People as well as council members were collecting this waste in truckloads, using it to harden country roads, farm yards, and drives. According to information from Eternit, asbestos waste was disposed for free during the period 1935-1974. During interviews a longer period was mentioned, till 1989.

Asbestos emissions

In 1978 TNO-IMG started a national survey on asbestos emission levels amongst the general population (Boeft and Lanting, 1981). This resulted in three levels of emission, which were source dependant:

Sources: Around asbestos industries and traffic tunnels: 10-100 fibres/l air Large and medium sized cities with high traffic density: 1-10 fibres/l air Background, rural area with low traffic density: 0.1-1 fibre/l air

Both in the council of Goor and Hardewijk the presence of an asbestos industry was demonstrated by the emission data. Goor was the only location with a measurable emission of blue asbestos.

Asbestos country roads around the Hof van Twente

The Centrum of Milieukunde together with the Asbestos Project Group of the Stichting Arbeid and Gezondheid, Utrecht have conducted a qualitative survey on the use of asbestos waste as hardener of country road (Hennekam et al, 1984). On 83 country roads around the council, asbestos-containing waste was detected with a total surface of 33.500 m2. This source contained both loose asbestos and parts of asbestos cement waste and was regarded as a potential source of emission and exposure. Through weathering and traffic movements the cement matrix could be pulverised leading to an emission during dry periods of the year.

The survey above was followed up by a second survey of TNO-MT to estimate the size of the asbestos waste stream as well as the emission (Boeft, 1985; Boeft, 1987). The asbestos emission had the same order of magnitude as the 1978 survey. The size of the asbestos waste stream was calculated by assuming that 40 kg of asbestos waste is released per 1000 kg of product. For the period 1935-1974 the total amount of asbestos waste was estimated as 360 103 – 4.400 103 kg, both white and blue asbestos.

Asbestos and asbestos emission in the new housing estate De Hogenkamp

The commission was unable to trace the source of the asbestos pollution at the new housing estate unambiguously. But during the period of the acquisition of the

building site (1995) one of the premises was polluted with asbestos waste; 87 tons of asbestos cement waste was used to harden the drive and 30 tons of loose asbestos was found on and around the foundations of the barns. In the course of the building of the estate, the pollution became manifest during the decoration of the gardens. This event was drawing a lot attention in national media (Biesheuvel et al, 2003).

TNO-MEP conducted measurements at the new housing estate in 2002, the emission at three gardens was determined, including a so-called worst case simulation under laboratory conditions. Furthermore, a ground sample was taken from one of the garden, as well as a strip samples of the floor of a garage and a living room (Tromp en Tempelman, 2003). None of the air samplers contained asbestos, although the ground sample was heavily polluted with loose asbestos and asbestos cement waste. Only the strip sample of the garage contained asbestos fibres.

Non-occupational cases of mesothelioma

The Association of Integral Cancer Centres shows regional differences in mesothelioma mortality in different regions in the period 1989-1997. The age specific mortality amongst women in the provinces of Overijssel (Hof van Twente) and Flevoland (Harderwijk) are two times the national level (respectively 0.8 and0.9 per 100.000 persons) (Damhuis et al, 2000). These figures are a lot higher for the area of Hof van Twente. The non-occupational exposure to asbestos wasconfirmed in six female and four male cases of mesothelioma from the region.

Media attention to asbestos

From 1969 onwards more than 300 different asbestos related topics have been published in national newspapers (table 1). These articles focus on the hazards and risks of exposure to asbestos.

Dr Stumphius (1969) thesis on the effect of asbestos exposure at the shipyard De Schelde at Vlissingen attracted attention, similar to his announcement in 1976, when he declared the annual mesothelioma mortality would be around 100. In this period the Asbestos degree (1978) was in preparation and TNO organised a national asbestos conference in Delft (1977). 8 years later a second national asbestos conference was held, again in Delft at the Delft University of Technology (Swuste et al, 1985). Risks of asbestos were frequently subject of publications, and both TNO, Delft University of Technology, the unions and social organisations were advocating a total ban on asbestos. Articles, that reactivated the health risks were not published frequently. The first notice came in 1982, following the Montreal asbestos conference in Canada. Other articles were attributing the health risks to blue asbestos alone, like a publication in the NRC of February 14th, 1989 that was rebutted one week later. And a doctor on environmental medicine declared in 1993 ‘that you could eat asbestos’. This statement can only be understood as a reaction on the asbestos panic that broke out after a fire and resulted in a road blockade of a very busy highway.

The media archive shows there is a lot of attention on asbestos, both from The Netherlands and abroad, on research findings, on legal claims, and on economic consequences of legal procedures. Right from the start there was a strong call for strict legislation, and from 1988 onwards, major attention in the media is given to the collective settlement for asbestos victims. This settlement is unique for The Netherlands (Swuste et al, 2004). During the whole period articles were written on a great variety of asbestos problems, one of them being the new housing estate De Hogenkamp.

Official documents and council decision-making

A trade union report on the high levels of asbestos exposure at the Eternit factory appeared in 1976 (Industry union NVV and NKV, 1976). The reaction of the companies was defensive, pointing to the difference in opinion between leading experts, and announcing an Asbestos degree dispensation was granted for the use of blue asbestos, due to economic reasons. According to Eternit’s opinion white asbestos is not hazardous, when the necessary preventive measures are taken (Haaff, 1978). This opinion was not supported by the national commotion in the media on the health hazards of asbestos.

Within the council in the 1980ies the attention was shifting from occupational exposure at the Eternit factory towards the environmental emission to asbestos, and the presence of asbestos waste at country roads, farm yards, and drives. By the results of the national survey of TNO, the outdoor emission was becoming an item for the council. The conclusion of the survey, that exposures for the region Goor are relatively high, did not result in any action from the council. In reaction, Eternit posed the values for the region did not differ from any other industrial area. The results of the interviews showed this opinion was reassuring for the council, which lacked the knowledge and expertise to judge the results. According to the research committee a picture emerged of a council, which did not feel the need for external expertise. The council was waiting for a position of the Province in these matters.

In the late 1980ies the Ministry of Environment prepares a ban on asbestos that came into power July 1st 1993. In the council there was plenty discussion on the loss of employment, caused by the ban, and the council together with Eternit and the Province applied for dispensation from the ban. The minister did not examine this request.

The discussion on the hazards of the asbestos contaminated country roads became current halfway the 1990ies. Eventually this was leading to a national agreement, forbidding the ownership of these country roads, and the finally the council redeveloped het country roads without any external funding.

Administrative and official organisation around problems concerning asbestos

According to the research committee, the national signals on the hazards and risks of asbestos from 1976 onwards only penetrated the city council and the administrative organisation to a very limited extend. These external developments were far too wide for the official organisation of the council, while lacking the administrative and political support. The organisation of the council was strongly segregated, and public health was not an issue of any concern of the council.

Asbestos soil pollution

Administrators as well as council officials were aware of the Eternit’s distribution of asbestos waste, free of charge. The interviews revealed they did not have any notice on the size of this type of pollution. From 1992 onwards, the Socialist Party made the asbestos soil pollution a political item (Poppe en Senden, 1992). Not every administrator and public servant knew how to cope with this item. The council of Goor only had a relative small outer area, meaning the redevelopment of country roads was only a minor problem. Finally the redevelopment was carried out, with some resignation because the council did not receive any governmental funding.

Asbestos pollution at the new housing estate De Hogenkamp

De housing estate De Hogenkamp was a prestigious project, introducing sustainable housing, and selling the lots without interference of any real estate developer. According to administrators and public servants the time pressure on the project was high, and the official procedure for the zoning scheme was complex.

With hindsight a thorough soil research in combination with an historical soil research could foresee the sources of asbestos pollution. During the purchase of the soil by the council in 1995 and during the preparation of the site for building these types of research were only executed marginally, because the need for an extensive research was not seen as an important item. In the same period also the regional municipal reorganisation was an important item, leading to an administrative chaos. Both administrators and public servants are left with serious doubts. No one understands the origin of the asbestos pollution, nor the extensive media attention to this topic. Administrators do see the consequences of the negative publicity, and see the citizen’s confidence in municipal services and decision-making is harmed.

Risk perception on asbestos

For both administrators and public servants asbestos and Goor are inseparable, due to the presence of the Eternit factory. The interviews showed most administrators and public servants believe the hazards and risks of asbestos are grossly exaggerated. They refer to the statements of Eternit, to Belgian law, which do not know a ban on asbestos, and to other branches of industry where asbestos is a much bigger problem according to their views. Frequently the branch of shipbuilding is mentioned in this respect. Another argument is the observation that not everybody exposed to asbestos will attract asbestos related diseases. This resulted in an attitude amongst citizens, administrators and civil servants of the council that ‘asbestos, it won’t be so bad’. According to the research committee the

picture is generated of a council that is does not take the health risks of asbestos seriously and is strongly influenced by Eternit’s risk assessment. The economic position of the company is an important argument for this attitude. Eternit is seen as a important and stable employer for the region.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

The asbestos pollution in the council of Goor is substantial, regarding the estimated amount of the asbestos waste stream from the factory. Probably this type of pollution is not restricted to Goor but can be found at any council with a extensive asbestos industry, and a agricultural surrounding countryside.

The national survey of TNO-IMG on asbestos emission has shown the presence of an asbestos industry at Goor. The emission measurements are one of the highest measured. Close to the local Eternit plant at the Italian town of Casale Monferrato the values measured are of the same order of magnitude.

Apart from the industrial activities also the asbestos waste stream, used as hardening material on country roads, generates a measurable emission and exposure to asbestos. Also the emission values on blue asbestos are high. Both the information from claims, and from the regional hospital, and from the Association of Integral Cancer Centres provide an indication the asbestos polluted country roads generate an excess mortality on mesothelioma. The mesotheioma mortality amongst women can be seen as an indicator of an environmental exposure to asbestos. The results of the survey in Casale Monferrato are pointing to a similar problem in the council of Hof van Twente. Additional research should clarify this assumption.

Despite the asbestos contamination of the soil, asbestos pollution at the new housing estate did not generate a measurable emission on asbestos. Probably the amount of free asbestos at the surface is much lower than at the asbestos polluted country roads, where passing traffic causes emission.

From the second half of the last century onwards the former council of Goor has been strongly associated with the asbestos company of Eternit. This company was one of the biggest employers in the region. Halfway the 1970ies the council regarded hazards of asbestos as an internal affair of Eternit. Actually, for years the council was in a clasping grip of Eternit. On one hand Eternit systematically belittled the hazards of asbestos, and the council did not take the asbestos emission and pollution of country roads seriously. On the other hand the council preconceived employment arguments at least till the beginning of the 1990ies, as the request for dispensation from the ban on asbestos in 1993 showed. The council keeps on reacting reactively and is unable to define a major hazard scenario.

The state of affairs during the ambitious new housing estate project De Hogenkamp reflects a similar attitude. According to the research committee various signals were given, pointing at substantial asbestos soil pollution, and none of these signals have been picked up. The council project group does not address this aspect adequately.

Regarding the third question there are two possibilities. Either the responsibility for an integral asbestos policy is not the council’s concern, or the council should appoint a special project team for future building activities that can operate according to a risk management approach. The first option has its pro’s, because the council operates in a field of conflicting interests. She has to authorise and uphold permits for a company that generates a substantial employment and determines the economy of the council and region for a great deal. The central government can take over the direction of the environmental policy of the council. Nevertheless the council can not escape the second option, if in future times more examples of asbestos soil pollution will be announced. She needs to integrate a

project group both in the administrative and public services. This means the information services and the feedback on plans, and results of soil research has to be adequately managed between project group and council’ policy makers. At the same time, those with administrative responsibilities need to be supplied with condensed information, regarding the hazards, risks, and hazard scenarios. As a starting point the following scenario’s can be considered:

- 1. The historical exposure to asbestos from different sources is resulting in a future mortality of asbestos related diseases. The council cannot influence this scenario, but the council can start an information point for citizens and former asbestos workers. This scenario will generate victims for decennia to come, and the information point can support asbestos victims to obtain a financial compensation. For asbestos workers the Institute of Asbestos Victims provides these services. Nonoccupational asbestos victims only can follow the long lasting legal route for an asbestos claim.

- 2. Country roads hardened with asbestos give rise to exposure of neighbours and enhance the chance for mesothelioma. This scenario is within the sphere of influence of the council. The size and the consequences of this form of pollution can be investigated.

- 3. Future building activities in asbestos polluted soil will create an exposure en will enhance the chance for mesothelioma. Also this scenario is within the sphere of influence of the council. A default premise is the asbestos pollution of the soil concerned. In the Biesheuvel report recommendations were made for the required quality of the soil research.

- 4. Asbestos products create an asbestos exposure.

- 5. The media attention for De Hogenkamp has led to a reaction of panic among inhabitants.

The fourth and the fifth scenario deal with an efficient provision of information. The asbestos panic is a special case. Information services probably will have alimited effect on the ruling perception in the district. Citizens of the district needto get the impression the council will deal with their problems seriously, and the council will try hard, regardless the outcome.

REFERENCES

Baris, Y. Sahin, A. Ozesmi, M. (1978). An outbreak of pleural mesothelioma and chronic fibrosing pleurisy in the village of Karain/Urgua in Anatolia. Thorax 33 p. 181-192

Biesheuvel, JP. Buurmeijer, F. Swuste, P. (2003). Asbestos from Goor to the Hof van Twente. Final report of the temporary research committee (in Dutch). Hofvan Twente.

Boeft, J. den, Lanting, R. (1981). Asbestos and other minerals in the environment (in Dutch). Rapport G 856, IMG-TNO, Delft

Boeft, J. den (1985). Asbestos concentration measurements close to asbestos polluted country roads in Diepenheim (in Dutch). Rapport R 85/312, MT-TNO,

Delft

Boeft, J. den (1987). Asbestos concentration measurements close to asbestos polluted country roads in Diepenheim (in Dutch). Rapport R 87/155, MT-TNO, Delft

Bohling, H. Hain, E. (1973). Cancer in relation to environmental exposure. In: Biological effects of asbestos. Bogovski, P (ed), p. 217, Lyon, IARC

Bourdès, V. Boffetta, P. Pasini, P. (2000). Environmental exposure to asbestos and

risk of pleural mesothelioma: review and meta analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology 16 p. 411-417

Burdorf, L. Swuste, P. Heederik, D. (1991). A History of awareness of asbestos disease and the control of occupational asbestos exposure in The Netherlands.

Historical perspectives in occupational medicine. American Journal of Industrial

Medicine 20 p. 547-555.

Dahhan, M. Burdorf, A. Swuste, P. (2003). Occupational histories of cases of

asbestos related diseases in The Netherlands (in Dutch). Tijdschrift voor toegepaste Arbowetenschap 16 nr. 3, p. 59-64

Dalquen, P. Dabbert, A Hinz, I. (1970). The epidemiology of pleural mesothelioma.

A preliminary report on 119 cases from the Hamburg area. German Medicine 15p. 89-95

Damhuis, R. Dijck, J. van, Siesling, S. Janssen-Heijnen, M. (2000). Lung cancer and mesothelioma in the Netherlands. Vereniging integrale Kankercentra, Utrecht. Haaff, ‘t. (1978) Hazards of asbestos depends on the safety policy in companies (in

Dutch). De Onderneming, 8 September, p. 9

Hennekam, M. Kaper, W. Kole, M. Reinders, A. (1984). Asbestos cement waste as road hardening material. An inventarisation of country roads around Goor (in Dutch) Centrum voor Milieukunde, Asbestprojectgroep, Leiden

Industriebond NVV en NKV (1976). First report of a survey to the occupational hazards of asbestos at Eternit, blackbook (in Dutch) Industriebond NVV en NKV, Hengelo

Industriebond NVV en NKV (1977). Second report of a survey to the occupational hazards of asbestos at Eternit, redbook (in Dutch) Industriebond NVV en NKV,

Hengelo

Magnani, C. Terracini, B. Ivaldi, C. Botta, M. Budel, P. Mancini, A. Zannetti, R. (1993). A cohort study on mortality among wives of workers in the asbestos cement industry in Casale Monferrato, Italy. Britsh Journal if Industrial Medicine 50 p. 779-784

Magnani, C. Dalmasso, P.Biggeri, A. Ivaldi, C. Mirabelli, D. Terracini, B. (2001) Increased risk of malignant mesothelioma of the pleura after residential ordomestic exposure to asbestos: a case-control study in Casale Monferrato, Italy.

Environmental Health Perspective 109 p. 915-919

Magnani, C. Agudo, A. Gonzalez, C. Andrion, A. ea (2000). Multicentric study on malignant pleural mesothelioma and non-occupational exposure to asbestos. British Journal of Cancer 83 p. 104-111

Newhouse, M. Thompson, H. (1965). Mesothelioma of pleura and peritoneum

following exposure to asbestos in the London area. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 22 p. 261-

Poppe, R. Senden, W. (1992). Asbestos at Hof van Twente (in Dutch). Socialistische Partij, Rotterdam

Segura O. Burdorf A. Looman C. (2003). Update of predictions of mortality from pleural mesothelioma in the Netherlands. Occupational and Environmental

Medicine, 60, p. 50-55

Swuste, P. Burdorf, L. Vliet, L. van. (1985). Asbestos, the replacement of the magic mineral. Proceedings of a symposium September 3rd (in Dutch). Vakgroep Veiligheidskunde, Delftse Universitaire Pers, Delft

Swuste, P. Burdorf, A. Klaver, J. (1988). Asbestos, the insight in the hazardous consequences in the period 1930-1969 in The Netherlands (in Dutch) Delftse

Universitaire Pers, Delft

Swuste, P. Burdorf, A. Ruers, B. (2004). Asbestos, asbestos diseases and compensation claims in The Netherlands. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health (in press)

Stumphius, J. (1969). Asbestos in an industrial population (in Dutch). Van Gorcum

Papers relacionados