Mearns, Kathryn

Department of Psychology / Aberdeen University / Kings College, Old Aberdeen, AB24 2UB Scotland, UK

+44 1224 273217 / k.mearns@abdn.ac.uk

Håvold, Jon Ivar

[1]

Ålesund University College / N-6025 Ålesund, Norway

+47 70161223 / jh@hials.no

ABSTRACT

Since its introduction in 1992, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) has rapidly gained in importance throughout the world. Harvard Business Review even selected it as one of the most important management tools of the past 75 years. Reasons for including occupational health and safety in the BSC and review of reports/papers covering occupational health and safety and the BSC are discussed.

This paper also takes the results of an offshore benchmarking study carried out by Aberdeen University on 13 offshore installations and relates it to the BSC. The results from the benchmarking study are discussed from the perspective of suggesting which indicators should populate each part of the BSC. In addition the paper include the results of interviews conducted with senior managers in the UK and Norwegian oil and gas sector, about use of the BSC in general and with regard to health and safety performance indicators in particular.

Keywords

Balanced Scorecard, performance measurement, occupational health and safety.

INTRODUCTION

Criteria for good measurement

Regardless of which framework is used to design and implement a system for measuring organisational performance, several criteria need to be addressed in creating good measures.

In general, a good measure:

- is accepted by and meaningful to the customer/stakeholders;

- tells how well goals and objectives are being met;

- is simple, understandable, logical, and repeatable;

- shows a trend;

- is unambiguously defined;

- allows data to be collected in a transparent and unambiguous way;

- produces timely and useful reports at a reasonable cost

- comprises a balanced set of a vital few measures

- supports the organisation's values

Above all, however, a good measure drives appropriate action.

The Balanced Scorecard (BSC)

The BSC is probably the world’s best-known organisational performance measurement system. Kaplan and Norton [1] start their article "The Balanced Scorecard - Measures that Drive

Performance" in Harvard Business Review with these words: "What you measure is what you get. Senior executives understand that their organisation's measurement system strongly affects the behaviour of managers and employees."

During the last few years progressive industry leaders have discovered that measurement plays a crucial role in translating business strategy into results.

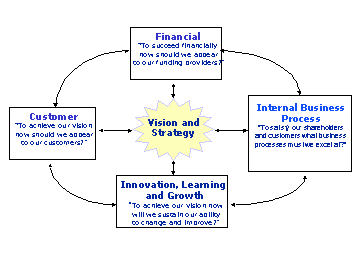

The BSC contains a diverse set of performance measures divided into 4 groups: financial performance, customer relations, internal business processes and learning and growth. The use of the balanced scorecard highlights the fact that there often is a lack of balance between the four perspectives and therefore a lack of balance between the short-term financial perspective (lagging indicators) and the drivers of future financial performance (leading indicators).

Figure 1 Balanced Scorecard

Kaplan and Norton [2] claim that a company's success for tomorrow rests as much on its ability today to measure the performance of less tangible assets such as customer relations, internal business processes and employee learning, as on its aptitude for monitoring traditional financial measures. BSC is designed to capture the firm's desired business strategy and to include drivers on performance in all areas important to the business. If safety is an important area for a company then it should be included as a driver in the scorecard.

Basic requirements for a BSC

‘If you don’t know where you’re going, chances are you will end up somewhere else’ – Yogi Berra

‘You can’t manage what you can’t measure’ - Drucker

There are a number of basic requirements for an effective BSC:

- The organisation has to know where it would like to go and how it will get there. The BSC will force management to focus upon a number of measures that are critical. Management must invest the resources to find those critical measures and understand how directions and milestones fit together.

- The organisation must understand that the scorecard is a longterm exercise. It is a tool for implementing business strategy. If it is used consistently management can compare "apples" with "apples".

- Management must have the maturity to use the results of the scorecard for continual improvement and not look for faults in the measures if they see something they don't like.

- The BSC must reach down the organisational structure and back up again. It is a tool for departments as well as senior management, and the scorecards must be linked together.

- Parameters must be objective and the data gathering process should be transparent to people using the information or being measured.

- It is unrealistic and demotivating to measure people on things they cannot control.

Aims of present paper

In this paper the following issues concerning BSC and occupational health and safety will be examined:

- Outline characteristics of measures for occupational health and safety

- Reasons for including health and safety in a BSC

- Review work done on occupational health and safety measures for use in BSC)

- Suggest indicators of occupational health and safety, and how these measures can be integrated into a wider framework like the balanced scorecard.

- Further developments

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY AND THE BSC

Characteristics of measures for occupational health and safety

Most businessmen would want simple and low cost measures (if possible a single indicator) covering every main area. It would be optimal if such a measure were to be found, but occupational health and safety experts say that no such single measure can be completely adequate to measure occupational health and safety [3]. One reason for this may be that health and safety issues are dynamic in nature. Discussions with senior health and safety managers from the UK offshore industry support such a supposition. In managing health and safety they find that once one problem is ‘fixed’, another problem surfaces in its place. This is probably due to the complexity of the socio-technical systems that characterise high hazard, high reliability industries such as offshore, nuclear, chemical and aviation. Some theorists believe that where people and complex technology meet, there are always going to be safety problems and accidents are a ‘normal’ characteristic of such systems [4].

If this is theory is accepted then the implications are that risks can only be managed and never entirely eliminated. In other words, there is no such thing as ‘zero risk’. This means that organisations have to keep constant vigil to determine potential weaknesses in their health and safety management systems, in order to keep risks as low as reasonably practicable. The process of monitoring would be greatly enhanced by identification of the critical ‘leading’ performance indicators that have an impact on health and safety performance further down the line, i.e. accidents and incidents.

A recent publication [5] from the UK regulator, the Health & Safety Executive (HSE) supports the arguments outlined above and recommends a ‘Balanced Scorecard (BSC) approach’:

"Organisations need to recognise that there is no single reliable measure of health and safety performance. What is required is a "basket" of measures or a "balanced scorecard" providing information on a range of health and safety activities." [5] p5.

The same publication [5] also underlines the characteristics that make measures for occupational health and safety different from indicators for other areas:

"Health and safety differs from many areas measured by managers because success results in absence of an outcome (injuries or ill-health) rather than presence. But a low injury or ill-health rate, even over a period of years, is no guarantee that risks are being controlled and will not lead to injuries or ill-health in the future. This is particularly true in organisations where there is a low probability of accidents but where major hazards are present. Here the historical record can be a deceptive indicator of safety performance." [1] p5.

Why include health and safety in the BSC?

Obviously, industry is acutely aware of the ethical and moral implications of killing and injuringpeople at work. Many managers claim that this is the main motivator for ongoing efforts in health and safety within organisations, however, there is little doubt that accidents can also influence an organisation’s present and future competitive success. For example, the Piper Alpha disaster in the UK North Sea in 1986, which claimed 184 lives, led to the end of Occidental’s operations on the UK Continental Shelf. Accidents and incidents have both direct and indirect costs and might influence growth and profitability for a business. The recent demise of Railtrack (the privatised rail network provider in the UK, recently taken over by the Government) can largely be attributed to failures by the company to monitor the state of safety within the organisation. Accountants largely ran the company (apparently they did not have a single engineer on the board of directors), who appeared to be most focused on financial profit and keeping trains running on time. As a result, Railtrack failed to take notice of potential safety problems, e.g. badly positioned signals, wear and tear of railway track, which led to the Ladbroke Grove and Hatfield rail disasters.

In 1997 the HSE published a report entitled “The Cost of Accidents at Work” in which they claim that incidents might account for as much as 37% of annualised profits for a transport company, 8.5% of the tender price for a construction site and 5% of running costs for a hospital [6]. For every pound of recoverable insured cost, employers in the study were faced with between £8 and £37 of uninsured costs. Many people do not realise how expensive accidents are. In fact many expenses are not always obvious. The modern study of accident costs began with the work of Heinreich [7] during the 1920s. He considered thousands of cases and came to the conclusion that management grossly underestimated the cost of injuries on the job.

Another problem, if we look at the total costs of accidents, is that they occur on several levels: private, company and society and we must we bear in mind when we discuss the economic side of accidents that the most important costs of are non-economic. These include the directphysical costs to the victim, the emotional costs to the victim's family and community, and damage to social values like justice and solidarity.

The listing below is limited to costs at the company level.

Table 1. Examples of Potential "Indirect Costs" of Occupational Accidents at the Company Level

|

Interruption in production immediately following the accident |

|

Morale effects on co-workers |

|

Personnel allocated to investigating and writing up the accident |

|

Recruitment and training costs for replacement workers |

|

Reduced quality of recruitment pool |

|

Damage to equipment and materials (if not identified an allocated through routine accounting procedures) |

|

Reduction in product quality following the accident |

|

Reduced productivity of injured workers on light duty |

|

Overhead cost of spare capacity maintained in order to absorb the cost of accidents |

|

Market share reduction / Customer retention |

|

Management must leave company |

|

Lost goodwill |

|

Difficult to get the right kind of people to work in a company with bad reputation |

|

Less support from local community official bodies |

|

Higher insurance premiums, difficulties to get insurance |

|

Financing problems / stock exchange |

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY MEASURES FOR USE IN BSC

National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (Australia)

Gallagher et al [3] discuss in their report to the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission how occupational health and safety outcomes and occupational health and safety management systems can be best measured. They conclude that there is no easy way to find measures, because the complexity of occupational health and safety is such that simple quantified measures are inadequate and traditional measures like incident/claims data has proven unreliable.

"A Balanced Scorecard approach tailored to the special characteristics of

OHSMS[2] is advocated as an effective way of combining multiple measures,and reflecting different stakeholder interest in an operational OHSM plan," [3]page IX.

In table 2 indicators for each perspective in the BSC is suggested.

Perspective Dimensions of OHSMS Measurement Objectives (examples) Type of Data Business, Organizational& Financial Perspective All OHSMS Capture qualitative and quantitative outcome data to review performance Reputation, claims & benchmarking data Stakeholder Perspectives: Internal(such as employees) External(such as Government, agencies, trade unions, contractors etc.) Voluntary / Mandatory Monitor outcomes Employee satisfaction with OHSMS Compliance of OHSMS with Government & other external stakeholder requirements Incident data Employee feedback mechanisms, PPI[3] data External stakeholder feedback (including the use of PPI & audit data) Internal Business Process Perspective Safe Person / Safe Place Traditional / Innovative management structure / style Incident and quality of OHStraining Measures to identify, assess and control hazards Assessment of senior management activity and level of involvement Assessment of integration into general management systems Assessment of extent andquality of employee involvement PPI data PPI, audit and benchmarking data PPI. Audit & benchmarking data; manager and employee feedback Learning and Growth Perspective Development level Assessing extent of OHSMSdevelopment Meeting system specifications Continuous improvement Verification audit & PPIdata Verification audit Validation audit & PPI data

Source: Gallagher et al: Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems. A Review of their Effectiveness in Securing Healthy and Safe Workplaces. NOHSC, Sidney 2001

The proposed indicators mainly include output and process measures.

Health & Safety Executive (UK)

A new document developed by the UK Health & Safety Executive [5] provides practical guidance on measuring health and safety performance. As mentioned earlier, in the document they recommend a "basket" or a "balanced scorecard" providing information on a range of health and safety activities.

In the document they also emphasise some of the problems with injury and health statistics:

- Under reporting

- Whether a particular event results in an injury is often a matter of chance. An organisation can have a low injury rate because of luck or fewer people exposed, rather than good health and safety management.

- Injury rates often do not reflect the potential severity of an event, merely the consequences.

- People can stay off work for reasons that do not reflect the severity of the event.

- There is evidence to show there is not necessarily a relationship between "occupational" injury statistics and control of major accident hazards.

- A low injury rate can lead to complacency.

- A low injury rate can result in few data points being available.

- There must have been a failure, an injury or ill health, in order to get a data point.

- Injury statistics reflect outcomes not causes.

The HSE document [5] does not discuss which measures belong to the different perspectives of the BSC but recommend that performance measurements should be based on a balancedapproach which combines the following three types of measurement:

Input measures: Measures of the hazard burden.

These are characterised by the nature and distribution of hazards created by the organisation’s activities (i.e. different industries have different hazard burdens). Input measures are monitoring activities that give information on the significance of hazards, variation of hazardsacross the organisation and variation of hazards over time. These measures also determine whether the organisation is successful in reducing or eliminating hazards and what impact changes in the business have on the nature and significance of hazards.

Process measures: Measures of health and safety management system and activities to promote a positive health and safety culture (Leading indicators).

These measure organisational factors such as policy, organising, planning and implementation,performance, operation, maintaining and improving the systems and the development of a health and safety culture. This can be done by audits, reviews, surveys etc.

Outcome measures: Measure of failures (Lagging indicators).

These are reactive measurements such as injuries and work related ill health and other losses like damage to property, incidents, hazard and faults, weaknesses or omissions in performance standards or systems.

Aberdeen University study (UK) [9]

Lately there seems to have been a trend away from the use of traditional outcome measures,i.e. failures of safety in the form of accidents and incidents, toward multiple measures that can take account of various stakeholders' interests and assist both internal and external benchmarking. A study by Mearns et al [8] reviewed the literature and discussed benchmarkingin safety and health areas for the offshore industry. The review underlined the fact that it was important that the measures used in benchmarking gave top managers a fast and comprehensive view of the business on several levels. To find ‘best practice’, and let benchmarking become a motivator for improvement, it is advantageous to have benchmarks from internal and external operations from similar functions in other industries and from the industry both inland and abroad.

The study was set up as a collaborative Joint Industry Project (JIP) between the Offshore Safety Division (OSD) of the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and 13 offshore oil and gas companies (including operating companies, contracting companies and drilling companies) [9]. Although 13 different companies were involved, the benchmarking process was set up on an ‘installation’ level, not by company. This was due earlier research [10, 11] that had shown that offshore installations differ very much in their health and safety performance, despite being operated by the same company.

A project steering group was set up consisting of representatives from the University of Aberdeen, OSD HSE, and each participating company. The first phase of the study involved lengthy discussions between the research group and the representative managers in order to determine what health and safety performance indicators each company was using. This process allowed selection of a common set of indicators for the purposes of benchmarking. The performance indicators were also selected in order to fit into the BSC framework.

Earlier work by Mearns and co-workers [10, 11], had identified a set of ‘safety climate’ factors,i.e. measurements of workers perceptions of the ‘state of safety’ at their place of work, that were associated or correlated with self-reported accidents. In the current study these safety climate factors included ‘communication’, ‘workforce involvement’, ‘perceived management’, ‘perceived supervisor competence’, ‘satisfaction with safety activities’, ‘willingness to report accidents/incidents’ and ‘self-reported unsafe behaviour’. The steering group decided that ‘safety climate’ indicators represented the ‘customer perspective’ of the BSC, although some of the HSE managers also suggested that the senior management of their own organisation represented the customer perspective and the contracting company/drilling company managers felt that the operating companies were the ‘customer’.

In addition, a vast array of potential performance indicators were identified for the ‘internalbusiness’ perspective, many of them associated with engineering controls, risk assessments and control of process. In order to arrive at a common set of indicators that could be ‘benchmarked’ and which reflected ‘business process’ aspects of health and safety, HSG(65) ‘Successful health and safety management’ [12] was used as a framework. The indicators chosen related to policies and practices in six main areas:

- 1. Health and Safety Policy (i.e. exists, meets legal requirements and best practice, upto date, is being implemented effectively),

- 2. Organising for Health and Safety (control, communication, cooperation, competence),

- 3. Management commitment,

- 4. Workforce involvement in health and safety activities, including risk assessment and control,

- 5. Health and Safety auditing.

Finally, members of the steering group requested an extra section in the Safety Management Questionnaire (SMQ) that measured activities surrounding,

6. Health surveillance and promotion.

A Safety Management Questionnaire (SMQ) was designed incorporating a range of indicators under each of the six sections. This data was both quantitative and qualitative in nature and scores were derived from this data for each section and totalled for the entire SMQ.

Aberdeen University Petroleum Economic Consultants (AUPEC) were sub-contracted to investigate the ‘Financial perspective’ in terms of loss-costing data from incidents and accidents experienced by the various companies on the installations that had been put forward for the benchmarking exercise. It soon became apparent that very few of the companies involved actually collected loss-costing data, and at the end of the day only three companies were able to provide such data. Only limited conclusions can be drawn from such a small sample size but the data reveal that total costs varied from £2,476 per POB for one installation, to £10,769 per POB for another. There were major categorical differences in the costs reported by each company – Company A’s cost driver was production related, Company B’s cost driver was people related, and Company C’s cost driver was asset related. Company C provided no people-related costs, and as such their total costs may be a significant underestimate of the true costs incurred. Unless Company C did not incur people related costs, their total costs do not provide a meaningful comparison with the other two companies.

As a result of the lack of adequate data from a loss-costing perspective an attempt was later made to collect data on ‘investment in safety’, however this proved equally difficult due to safety costs to the organisation being tied up in operational budgets. For example, does a valve replacement constitute a safety cost (in terms of replacing old and redundant valves that may fail) or does it constitute an operational cost (to increase the flow of hydrocarbons for production purposes)?

In many ways the bottom line measure for safety is usually ‘accidents’ and ‘incidents’, determined either as a frequency or a rate. In order to collect systematic data from the installations involved in the study, accident and incident data collected under the mandatory RIDDOR [13] (Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations, HSE, 1995, see Appendix 1 for details) was used as an outcome measure of safety.

Results

Safety climate data from the installations was collected in the summer of 1998 and the summerof 1999. Correlational analysis (Pearson Product Moment) revealed a number of significant associations between factors derived from the offshore safety questionnaire (OSQ) and RIDDOR data. For example, in 1998 ‘communication’ was significantly correlated with the RIDDOR rate provided by the official installation figures. Communication of health and safety issues to the workforce has been viewed as a key stage of organisational learning that proceeds from accident / near miss investigations, safety audits or changes to procedures. The OSQ scale addressing ‘involvement in health and safety decision-making’ was significantly associated with the rate of lost time injuries in 1998 and with RIDDOR data in 1999. A sense of involvementmay be fostered by immediate supervisors during day to day tasks as well as the specific design of safety programs but in both cases evidence suggests that high involvement promotes safer working practice [13, 14]

Safety management practice displayed wide variation across installations. In 1998, lower self- reported accident proportions were observed on installations with favourable SMQ scores for management commitment, and health promotion and surveillance. In both years all coefficients were in the correct direction. In both years, favourable total SMQ scores were associated with lower rates of lost time injuries. Health and safety auditing was implicated in both years. Effective health and safety auditing can be viewed as a first line defence in preventing injury. Griffiths [15], among many others, includes auditing as a key requirement in any effective safety management system, and the theme of auditing emerges in safety diagnostic tools, not least among these the Process Safety Management System [16]. Shannon

et al [17] in their review identified five studies that included a measure of auditing proficiency, and four of the these studies associated proficient auditing with lower injury rates. Contrary to expectations, management commitment was positively associated with the rate of dangerous occurrences (i.e. releases of hydrocarbon inventory) in year one. It may be the case that high rates of dangerous occurrences the previous year motivated a higher level of management commitment and that changes in management commitment were reactive rather than proactive.

On the basis of the leading performance indicators that showed a relationship with RIDDOR rates on the participating installations, the following sets of indicators have been selected to populate the various perspectives of a BSC for the offshore oil and gas industry (see Table 3).

Table 3. Results from Mearns et al (2000) BSC

|

Financial |

Customer |

Internal Business |

Learning and Growth (Best Practice) |

|

Accident costs, i.e. loss costings Investment in safety,e.g. safety training budget Accidents and incident rates |

Levels of communication about health and safety issues Workforce involvement and ‘ownership’ of health and safety issues |

Health and safety policies Organising for safety;· Control· Communication· Co-operation · Competence Demonstration of management commitment and workforce involvement in health and safety Health and safety auditing Health surveillance andpromotion |

Testing of employees knowledge of health and safety policy Visits by managing director, business unitmanager/director to the installation, including faceto discussions withmembers of the workforce High percentage of staff attending safety committee meetings once a month Occupational health plan in place, high percentage of plan achieved and health promotion activities offshore High % of corrective actions formally closed out against an agreed time scale of the past year |

INTERVIEWS WITH SENIOR MANAGERS FROM THE NORWEGIAN AND UK OIL SECTOR.

In order determine the extent to which the BSC has been adopted by the offshore oil and gas industry in the UK and Norwegian sectors, interviews were conducted with senior health and safety managers from six companies (three in the UK and three in Norway). The interviews were carried out in December 2001 and January 2002 and asked about the use of the BSC in general and with regard to health and safety performance in particular. The sampling can beclassified as a judgement sample. The interviewees were contacted first by telephone and an interview guide was sent by mail to the managers agreeing to take part in the study. The information was collected both as personal and telephone interviews.

Five out of the six companies used a BSC approach to measure and manage their business, and those using BSC in the business also used it for monitoring health and safety performance. In fact, in these organisations health and safety performance was very much part of business performance.

Company 1.

Company 1 had a balanced focus on all parts of the business, not only the financial perspective and it was important that risks that can influence the financial side further down the road were included. This gave more comprehensive information and a broader scope of the actual situation. This manager believed that a broader spectrum of measures gave more shades and nuances, although they had not structured them into the different perspectives of the BSC. Instead the company was using Value based management based on key performance indicators (KPIs). The manager claimed there were no disadvantages with this system but a few challenges, for example it was demanding to find indicators to measure what it was the intention to measure.

Examples of SHE (Safety, Health and Environment) indicators included:

- Lost time injuries (How much time is lost by injuries )

- M-value

- TRI (Total Recordable Injuries)

- Incidents reportable to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate

- Chemicals to air/sea etc related to production unit (pr barrel), divided into two groups dependent on how dangerous they are.

- Chemicals etc related to drilled meter

- Contravention of operating permits (number)

The manager reported that he was satisfied with this approach since it gave a focus onresults. The approach had to be dynamic with questions asked about the KPIs used, with those that did not function satisfactorily being changed. The company now found itself at a stage where they had to be cleverer at using KPIs, for example they were beginning to establish a questionnaire to map attitudes to safety within the organisation.

Company 2

This company reported no disadvantages related to the BSC in itself, but in relation to the measures/indicators used to populate the BSC. There needs to be conscious consideration of what to include in the BSC and it is easier to discover faults when using several indices andmore interconnection between the different spheres in the company has an educating effect. The company had not structured its indicators into different perspectives on the BSC but examples of SHE indicators included:

- Employee satisfaction

- Customer satisfaction (Owners and buyers)

- Internal efficiency

- Learning efficiency

- Critical incidents (two levels dependant on how serious the incident is)

- Number of deviations from operating permits

- Level of activity

- Sick leave, absence because of injuries

- Maintenance lag (number of systems out of order)

- SHE progress

Company 3

This company found that the BSC was a method of covering the different perspectives and all information in one place. Earlier each department and staff group had their own scorecard. The BSC allowed responsibility, control and co-ordination to move out into the hierarchy andthe staff organisation and functions were becoming partners in reaching the company’s goals instead of controlling bodies. This enabled all levels in the organisation to be tied together in a positive manner.

This manager felt there were no disadvantages but a few challenges surrounding use of the BSC, for example it was demanding to introduce and implement, many people were involved in the process and those who used to have their own goals and ways of controlling had to now co- operate. The people involved/responsible needed ‘staying’ characteristics and the relevant knowledge about the business areas.

Rather than the four perspectives, this company is using five and has split Internal business into SHE and Internal Processes.

Table 4. SHE (Safety, Health and Environment) indicators for company 3

|

Business area |

Area |

Result unit |

Task responsibility |

Work group |

|

|

Frequency personnel accidents |

X |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

Number personnel accidents |

x |

x |

|||

|

Frequency serious accident |

X |

x |

x |

||

|

Number serious accident |

x |

x |

|||

|

Gas leaks |

X |

||||

|

Unwanted emission to sea/ground |

|||||

|

Emission to sea/ground |

|||||

|

CO emission 2 |

|||||

|

Energy use |

X |

x |

x |

||

|

Waste handling |

|||||

|

Due SHE and quality measures |

x |

||||

|

SHE and quality costs |

|||||

|

Falling items |

x |

||||

|

Number of breaks of barriers |

|||||

|

Unwanted incidents |

|||||

|

Quality of delivered product |

|||||

|

Safety critical fault |

|||||

|

Energy use |

![]()

The indicators marked with x are compulsory for the time being. (Decided by top management)

- The whole is the most important, all parts of the business have to be covered.

- Safety is taken for granted in the oil business.

- Extremely demanding to implement and find general indicators in a fully integrated oil company.

- Top management has to be involved all the way

- The one leading a BSC project in such a large company has to follow things through even if it is a long process. "They laughed at us when we began, now there is a huge demand for us out in the organisation".

Company 4

Company 4 uses the BSC to measure and manage the business and safety and occupational health are very much part of the scorecard. One of the advantages of this approach is that the scorecard reflects what is important to the business coupled with areas of improvement. One of the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for the organisation is high potential incidents, which have shown a steady downward trend over the past 4 years and have been reduced by 30%. In contrast one of the disadvantages of the BSC is that it is both a business and bonus scorecard and there is an issue about being rewarded for HSE performance when one shouldperhaps be rewarded for HSE activities. The company has a cascade of scorecards from the main organisation down to subsidiary scorecards, containing KPIs that are relevant to each part of the business. Eighteen percent of the total business scorecard is attributable to HS&E. This company is also introducing the scorecard to its contractors and has developed leading indicators with other operating companies. These leading indicators include management visits (performance and plan) and performance against an HSE plan (e.g. 90% of plan completed). Senior managers have clear goals for occupational health and safety and have contracts outlining what they are accountable for, which are integral to reward and promotion.

Table 5 If using the BSC, the manager would put the indicators under the following perspectives

|

Internal Business |

Customer |

Financial |

Learning/Growth |

|

Total recordable case frequency (TRCF) High potential incidents (HPIs) |

Contractors and workforce |

Impact of major loss of containment Costs associated with leaks, lost production |

Measures of competence Measuring the skills portfolio |

|

Progress against plan for management visits and the HSE plan |

Company 5

Company 5 uses the BSC to measure and manage the business but tends to focus on output measures, because then the organisation knows exactly where it is (this is one of the advantages of the BSC). The disadvantage of the BSC concerns ‘dynamism’. In other words the business environment (and the health and safety environment) is constantly changing. This means that the set of performance measures used at one point in time may not be appropriate at another point in time. The outcome measures for H&S tend to be OSHA based (DAFWC – Days Away from Work Cases), which is of U.S. origin.

The company also uses the BSC to measure and manage H&S. There are a variety of individual performance contracts, which start with the CEO and Group Executives. This then cascades down through the business streams and onto individual work sites and installations. The individual performance contracts are not consistent but are widely divergent. More than 50% of them are concerned with operational control and go into the company statistics database.

The performance indicators used for measuring safety are what the manager would call ‘Level 1 indicators’ – in other words, are the processes happening or not? With regard to Upstream Global Operations this would include measures such as the number of safety audits and the number of STOP cards (STOP is a behavioural modification programmed originally developed by DuPont). An external party carries out this type of audit once every 3 years. There is also a process of annual self-assurance and more frequent audits/ checks are carried out closer to the workplace, e.g. the number of permits coming through. Level 2 indicators could be characterised by ‘is the process operating effectively’ and Level 3 indicators are represented by ‘is this the best?’ The manager gave the example of a chemical plant in Northern Ireland, which has an outstanding safety record second but no one really understands how this state of safety has been achieved, so there is no potential for sharing ‘best practice’. Finally, the manager referred to the fact that they had looked at the relationship between number of interventions/audits and Total Recordable Incidents (TRIs) and had found that, contrary to expectations, the number of TRIs increased as the number of interventions/audits increased.

Table 6 If using the BSC, the manager would put the indicators under the following perspectives

|

Internal Business |

Customer |

Financial |

Learning/Growth |

|

Auditing |

Managers and workforce |

Costs of accidents not a good measure |

Measures of training, assurance, competence |

|

Also more formal audits |

Workforce opinions on H&S not surveyed regularly but general survey carried out annually across the company |

Costs are dominated by production shut- down. Measuring costs involves a lot of effort for not much gain |

Learning from accidents does not appear at this level. Safety flashes say whether people have done anything |

When asked if he was satisfied with the present performance measurement system, this manager replied that he would like more performance measurement at Level 2 and then move on to Level 3, which is measuring the things that matter. His main concern about using the BSC for Health and Safety was that it might lead to a lot of measurements that mean nothing. A multi-faceted approach would be much better but each measure should be assessed/screened for its utility (cost/benefit analysis) and a case has to be made for the business process, i.e. what helps us measure the quality and what helps us measure what matters.

Company 6

Company 6 did not use the BSC to measure and manage their business. However, after an explanation of what the BSC involves, the manager agreed there would be advantages in using this approach and that the company were measuring some of the perspectives in the BSC anyway. He thought that the BSC would provide a systematic framework for integrating information about the business, but the company had no plans to use it in the future. He was not entirely satisfied with the present performance measures, especially those for health and safety, although satisfaction with PIs for financial performance, operational performance were perceived as satisfactory.

Since Company 6 was not using the BSC to measure and manage the business, safety and occupational health were not part of the BSC either. The company, however, was using a number of performance measures/indicators (PIs) for health and safety. Within managers and supervisors performance contracts they were measuring Safety PIs and Environmental PIs (but nothing on occupational health). These performance contracts cascade right down the organisation to teams on the offshore installations. The safety PIs are made up of lagging indicators such as the LTI rate and other RIDDOR measures. The leading indicators were ‘Reporting of accidents/incidents’, ‘Auditing’ and ‘Management Commitment’ and all the managers have a safety performance contract. The managers/supervisors/teams are allocated points on their performance contracts. Leading indicators are allocated positive points whereas lagging indicators (e.g. an LTI or a dangerous occurrence) are allocated negative points.

The manager was asked to indicate under what perspective of the BSC he would you place the different measures. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. The manager would put the indicators under the following perspectives

|

Internal Business |

Customer |

Financial |

Learning/Growth |

|

Auditing |

Everybody a customer for safety! |

Accidents/incidents |

Reporting |

|

Management Commitment |

That includes managers as well as the workforce |

Loss costing data for each site, includes business losses |

Accidents/incidents and learning from these |

|

Try and keep accident/incident loss separate from business loss |

The manager indicated that he was not entirely satisfied with the present performance measurement system and that there was still work to be done. In particular, it was difficult to put the performance measurement system into numbers. For example, the company had tried a system whereby people would be achieving 91% of performance targets in Year 1, 92% in Year 2 and so on, however, there is a limit to how far you can go with this. Now they have gone to a system where they measure both positive and negative aspects, but some people have exceeded their targets and they’re not sure why.

Conclusions

Table 7 is an overview of the interviewed companies. Five out of the six companies interviewedused a BSC approach in implementing their strategy. All of the companies used output measures, but fewer used process and input measures.

Table 7. BSC and the interviewed companies in Norway and UK

|

Company |

Using BSC approach |

Health and Safety included in BSC |

Using input measures |

Using process measures |

Using outcome measures |

|

1 (N) |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

2 (N) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

3 (N) |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

4 (UK) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

5 (UK) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

6 (UK) |

X |

X |

- The organisations in the study emphasise that a clear and cohesive performance measurement framework that is understood by all levels of the organisation and that supports objectives and the collection of results is needed. BSC helps determine potential relationships between ‘leading’ and ‘lagging’ indicators

- The interviews underline leadership as critical in designing and deploying effective performance measurement and management systems. Clear, consistent, and visible involvement by senior executives and managers is a necessary part of a successful BSC. Senior management should be actively involved in both the creation and implementation of an organisation's systems. The present study indicates that the chief executive officer is important both in articulating the mission, vision, and goals to various levels within the organisation, as well as being involved in the distribution of both performance expectations and results throughout the organisation.

- Effective internal and external communications are the keys to a successful BSC implementation. Effective communication with employees, process owners, customers, and stakeholders is vital to the successful development and deployment of BSC. Results and progress toward program commitments should be openly shared with employees, customers, and other stakeholders.

- Accountability for results must be clearly assigned and well understood. Accountability seems to be a key success factor.

- BSC measurement systems must provide intelligence for decisionmakers, not just compile data.

- Compensation, rewards, and recognition were linked to performance measurements for some of the companies in this survey.

- Some of the companies in the survey emphasised that BSC measurement systems should be positive, not punitive. The most successful performance measurement are learning systems that help the organisation identify what works and what does not so as to continue with and improve on what is working and repair or replace what is not working.

- Fighting complacency. Just because the system is being monitored and measured, this does not mean that unanticipated hazards or interactions of hazards can still arise.

- The BSC has to be reviewed periodically and questions have to be asked: are we measuring the right things are we making better decisions how can we improve our measures to get the information we need

- BSC/performance measurement is not an end in itself, but a vital tool to improve both shortterm and longterm occupational health and safety if it is implemented and followed

up continuously.

CONCLUSIONS

Although interviewees had a positive attitude to the BSC and the ones who had implemented the tool had achieved results, they indicated that there was a lot of room for improvement by deciding on and including new indicators in the scorecards. The companies using the BSC were quite early in the implementation process and did not have a lot of results to show yet. One aspect that seemed to be particularly challenging was selecting indicators that actually had an impact on performance. The Aberdeen University Health and Safety Benchmarking study revealed those leading indicators in terms of ‘installation safety climate’ and health and safety management practices that had an impact on safety performance in terms of accidents andincidents. With regard to employee perceptions of safety in the working environment, aspects relating to communication and workforce involvement seemed to have most impact on reducing accidents and incidents. There was also some indication that perceptions of management commitment played a role, with high levels of perceived commitment being associated with low accident rates. With regard to health and safety management practices it would appear that a focus on health and safety auditing had an impact on levels of dangerous occurrences and good health surveillance and health promotion activities were associated with lower lost time injury rates. Although the benchmarking exercise revealed relative strengths and weaknesses in safety climate and health and safety management practice across the installations, and it also indicated correlations between leading and lagging indicators, more data is required to determine the mechanisms that may be operating to give rise to these effects. For example, is investment in health promotion and surveillance another indicator of management commitment, or is it an indicator that an organisation is good at assessing risks and putting measures in place to mitigate against those risks?

Future research should be aimed at collecting longitudinal data. For example, are workforce perceptions of safety and safety management practices at time 1 associated with safety performance indicators such as accident rates at time 2. This type of relationship was explored in the benchmarking study. Workers’ satisfaction with safety measures and their levels of self- reported safety behaviour in Year 1 were highly and significantly correlated with self-reported accident involvement in Year 2, across the nine installations that provided data for both years.

A case study from the oil company Mobil is included in Kaplan and Norton's latest book: "The Strategy Focused Organization" [18]. Mobil reported that the number of safety and environmental incidents resulting in lost work was reduced by 80% and 63%, respectively, by including SHE measures in the BSC so the potential savings both on direct and indirect costs are substantial. The case implies that Mobil used only outcome measures such as safety incidents, days away from work and environmental incidents in their scorecard.

Our interviews indicate that occupational health and safety is important for the companies in oil and gas related industries implementing balanced scorecard. The companies using BSC included mainly outcome measures but process measures are starting to find their way into the scorecards of some of the organisations surveyed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1992) The balanced scorecard Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 70 (1): 71 79.

- 2. Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1996) The Balanced Scorecard. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School.

- 3. Gallagher, C., Underhill, E. and Rimmer M. (2001) Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems: A Review of their Effectiveness in Securing Healthy and Safe Workplaces. Report prepared for National Occupational Health and Safety Commission, Sidney.

- 4. Perrow, C. (1984) Normal Accidents. Living with HighRisk Technologies Basic Books.

- 5. HSE (2001) A guide to measuring health & safety performance. Health & Safety Executive, Discussion document. www.hse.gov.uk

- 6. HSE (1997) The costs of accidents. HS(G) 96, HSE Books, Sudbury.

- 7. Heinrich, H. W. (1959) Industrial Accident Prevention. A Scientific approach. (Fourth Edition) McGraw Hill, New York

- 8. Mearns, K.; Whitaker, S.; Flin, R.; Gordon, R.; O’Connor, P. (2001) Factoring the Human into Safety: Translating Research into Practice. Vol 1. Benchmarking human and organisational factors in offshore safety. HSE OTO 2000 036. HSE Books, Suffolk. 9. Flin R, Mearns K, Fleming M and Gordon R (1996) Risk Perception and Safety in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. HSE Report OTH 94 454. Norwich: HM Stationary Office.

- 10. Mearns, K.; Flin, R.; Fleming, M.; Gordon, R. (1997) Human and Organisational Factors in Offshore Safety. Report OTH 543. Offshore Safety Division. HSE Books, Suffolk.

- 11. HSE (1997) Successful Health and Safety Management. HSG 65. HSE Books, Sudbury.

- 12. Simard, M.; Marchand, A. (1994) The behaviour of first line supervisors in accident prevention and effectiveness in occupational safety. Safety Science, 17, 169185.

- 13. DePasquale, J. P. and Geller, E. (1999) Critical Success Factors for BehaviorBased Safety: A Study of Twenty Industrywide Applications. Journal of Safety Research 30 237249

- 14. Griffiths, D.K. (1985) Safety attitudes of management. Ergonomics 28 6167.

- 15. Hurst, N.W.; Young, S.; Donald, I.; Gibson, H.; Muyselaar, A. (1996) Measures of safety management performance and attitudes to safety at major hazard sites. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 9 161172.

- 16. Shannon, H.S.; Walters, V.; Lewchuk, W.; Richardson, J.; Moran, L.A.; Haines, T.; Verma, D. (1996) Workplace organizational correlates of lost time accident rates in manufacturing. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 29 258268.

- 17. Kaplan R. S.; Norton D. P. (2001) The StrategyFocused Organization. How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts.

- 18. Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1993) Putting the balanced scorecard into work. Harvard Business Review 71 (5): 134147

- 19. Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1996b) Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review 74 (1): 7585.

Appendix 1: Definitions of accident categories according to RIDDOR

-Fatalities: A death as a result of an accident arising out of or in connection with work.

-Major injury: An injury specified in Schedule 1 of RIDDOR ’95 including fractures, amputations, certain dislocations, loss of sight, burns, acute illness, hyperthermia / hypothermia, and loss of consciousness requiring hospitalisation for at least 24 hours.

-Lost time incidents of three or more days (LTI³3): A work-related injury resulting in incapacitation for more than three consecutive days.

-Dangerous occurrences: Any one of 83 criteria, including 11 specific to offshore detailed in Schedule 2 of RIDDOR ’95 with the potential to cause a major injury. This includes failure of lifting machinery, pressure systems or breathing apparatus, collapse of scaffolding, fires, explosion, and release of flammable substances.

-Near-misses: An uncontrollable event or chain of events which, under slightly different circumstances could have resulted in injury, damage or loss.

-Reportable diseases: An occupational disease specified in column 1 of Schedule 3 of RIDDOR ’95.

RIDDOR rate: The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (1997) provides the relevant equation for calculating a composite index of rates of fatalities, major injuries, lost time injuries and dangerous occurrences within any organisation. This index was used in as a lagging safety performance indicator.

[1] The author is also a PhD student at Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management / Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

[2] Occupational Health and Safety Management System

[3] Positive Performance Indicators (like number of safety audits; percentage of workers receiving safety training; percentage of sub standard conditions identified and corrected etc)