Jones, Richard

Institution of Occupational Safety and Health / The Grange / Highfield Drive / Wigston / Leicestershire / LE18 1NN, UK.+44 116 257 3100 / richard.jones@iosh.co.uk

ABSTRACT

This paper provides an initial report on UK involvement in the ENSHPO multinational survey into the role and tasks of occupational safety and health (OSH) practitioners, the aim of which is to collect comparative data by using a standard questionnaire. The paper briefly introduces the UK system of OSH regulation and advice provision; UK work activity and employment trends; and the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health. It then presents the UK data generated from 1,621 Registered Safety Practitioners, including the core tasks (33), hazards (22) and relationships (22). It establishes the diversity and complexity of the practitioner’s role and highlights potential areas for further research.

Keywords

OSH practitioner, occupational safety and health, roles and tasks, hazards

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Legislative development: occupational safety and health legislation in the UK began over two hundred years ago, with the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act in 1802, which concentrated on the health and moral welfare of the young working in mills and factories. With the rapid development in industrialisation, 1833 saw the first of a series of ‘Factories Acts’ (the last was in 1961), setting out the prescriptive measures to be taken to ensure the safety of factory workers. There was also corresponding legislation for various other sectors of industry, e.g. shipyards, mines, quarries, foundries, etc. and they all followed the same prescriptive formula [12].

In 1972, Lord Robens was commissioned by the government to carry out a thorough review of health and safety at work, with the aim of recommending improvements. His seminal report [13] led to the enactment of the Health and Safety at Work, etc. Act 1974 [4] – a major change in the regulation of workplace hazards. This introduced the first risk-based, goal-setting legislation, based on the principle that those who create the hazards should control them by appropriate means, proportionate to the level of risk posed. This initiated the widespread use of risk assessment, which became an explicit requirement with the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1992 (MHSWR), subsequently amended in 1999 [10]. The new approach to the regulation of workplace hazards led to significant improvement in OSH, with the number of deaths at work reduced to a quarter of the 1971 levels. The Health and Safety at Work, etc. Act 1974 also established two new institutions, the Health and Safety Commission (HSC) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

The UK regulatory system: the HSC, a body of up to ten people, representing employers, employees, local authorities and others, has the primary function of making arrangements to protect the health, safety and welfare of people at work and the public against work-related risks. Its role includes to: conduct and sponsor research; promote training; provide an information and advisory service; and submit proposals for new or revised regulations and approved codes of practice. It also has a specific duty to maintain the Employment Medical Advisory Service, which provides advice on occupational health matters.

The HSE, led by three people appointed by the HSC, advises and assists HSC in fulfilling its role. The HSE has a staff of around 4,000, including inspectors, lawyers, policy advisors, engineers, technologists and scientific and medical experts. It is responsible for the enforcement of health and safety law and delegates the enforcement of certain premises to local authority inspectors. The HSE’s enforcement areas include nuclear installations, mines, factories, farms, hospitals, schools, offshore gas and oil installations and railway safety and the 400 local authorities’ areas include retail, finance and leisure sectors [5].

OSH management: in the UK system responsibility for OSH management rests with employers and the self-employed, who are required to reduce risks ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’ i.e. until the taking of further measures would be grossly disproportionate to the residual risk. In 1991, the HSE published Successful health and safety management (HS(G)65), second edition 1997 [6], based on the ‘plan, do, check, act’ principle, which describes the five key system elements of policy; organising; planning and implementation; measuring performance; audit and review. As already mentioned, the MHSWR, first introduced in 1992, require employers to set up an effective OSH management system to implement their OSH policy and to have access to competent assistance in applying the provisions of OSH law. The government’s guidance explains that employers should ideally appoint someone competent within their workforce to this role, or if not feasible, engage a competent external service provider (possibly using both internal and external resources). For an individual to be deemed competent to give OSH assistance, the MHSWR state that they should have: “…sufficient training and experience or knowledge and other qualities to enable him properly to assist in undertaking the measures…”.

In addition to general OSH advice, employers may also need the services of different specialisms such as ergonomists, hygienists, OH nurses, OH physicians and physiotherapists. The MHSWR were introduced to implement Council Directive 89/391/EEC [2] and heralded a new approach to the management of OSH risk. This had a significant affect on the demand for OSH practitioners and led to a corresponding growth in IOSH membership, seeing it grow from 6,555 members in 1990 to 27,650 in 2004.

Work in the UK: the UK has a working population of 27.9 million people, employed in29.6 million jobs. Workforce jobs by industry in the UK can be broadly divided into three categories: a) agriculture and fishing (1.4%); b) industries (20%), including energy and water, manufacturing and construction; and c) services (78.6%), including distribution, hotels and restaurants, transport and communication, finance and business, public administration, education and health [11].

In recent decades, UK workplaces and the world in which they operate have changed significantly. There are fewer large firms and many more small ones in the UK, of the estimated 3.8 million businesses, 94.5% employ less than ten people, though nearly half of the workforce are employed in large organisations. There has been a change in the employment profile with a decline in manufacturing and a growth in the service

sector, increased part-time working and women now making up nearly half of the workforce. It is interesting to note that in the last 20 years finance and business services have increased by nearly 87%, whilst manufacturing has declined by over 30% (see table 1). Other factors to be considered include OSH issues associated with increases in downsizing and outsourcing; new immigrant workers; older workers; young people on work-experience or vocational training; mobility and travel as integral parts of work; home working/teleworking; and occupational security and stress issues, related to aggression and violence from the public and to terrorist threats.

Nearly all the new OSH challenges are in OH rather than in safety. In 2001-2, of the estimated 40 million UK working days lost to work-related injury and ill health, 33 million were attributable to ill health. The focus on OH has developed from the traditional areas such as chemical exposure and noise, to ‘new’ issues such as stress and musculoskeletal disorders, with greater emphasis on rehabilitation. The UK regulators priority areas are: work-related stress; musculoskeletal disorders; falls from height; workplace transport; slips and trips; and their priority employment sectors are agriculture; construction; and health services.

Table 1 – workforce jobs by industry, March 2003*, UK [11]

|

Workforce jobs (thousands) |

Per cent of workforce jobs |

Percentage Change 1983 - 2003 |

|

|

Agriculture and fishing |

415 |

1.4 |

-34.6 |

|

Energy and water |

209 |

0.7 |

-65.5 |

|

Manufacturing |

3,781 |

12.8 |

-31.4 |

|

Construction |

1,935 |

6.5 |

10.9 |

|

Services |

23,262 |

78.6 |

39.8 |

|

of which: |

|||

|

Distribution, hotels and restaurants |

6,863 |

23.2 |

28.1 |

|

Transport and communication |

1,809 |

6.1 |

13.7 |

|

Finance and business services |

5,712 |

19.3 |

86.9 |

|

Public administration, education and health |

7,094 |

24.0 |

29.0 |

|

Other services |

1,785 |

6.0 |

57.7 |

All jobs

29,602

100

17.8

* Seasonally adjusted.

Source: Office for National Statistics

About IOSH: formed in 1945 with just 60 members, IOSH now has over 27,000 members, is Europe’s largest OSH professional body and has strong OSH links worldwide. A Chartered body and registered charity, it is the guardian of OSH standards of competence in the UK and provider of professional development and awareness training courses. IOSH is consulted by government departments for the views of its members on draft legislation, approved codes of practice and guidance notes, and is represented on the committees of national and international standards- making bodies. The Institution regulates and steers the profession, maintaining standards and providing impartial, authoritative, free guidance on OSH issues. IOSH members work at a variety of levels across all employment sectors, public, private and voluntary and its vision is: “A world of work which is safe, healthy and sustainable”.

Since the foundation of IOSH over half a century ago, there have been many changes within the workplace and the profession. Fifty years ago the main concerns were preventing ‘traditional’ industrial accidents. Now, in the new millennium, issues such as ergonomics, stress, occupational hygiene and management systems commonly form part of the working life of the OSH practitioner. IOSH development has reflected these

shifting demands, with the launch of initiatives such as the Register of Safety Practitioners and the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programme.

Full corporate membership of IOSH (MIOSH) is open to those individuals who hold an accredited higher-level qualification and have at least three years’ experience as a safety professional. Some members who have degrees in subjects related to safety and health, and who practice in specialised areas, may also hold this grade. Full corporate members who have a minimum of three years post-qualification experience can apply to be accepted onto the Register of Safety Practitioners (RSP), but will need to demonstrate that they satisfy a broad spectrum of competences and be assessed by their peers as having done so. RSPs represent the higher competence level and can operate across the whole range of OSH activities and are required to maintain this level by undertaking mandatory CPD. The lower, non-corporate level of competence recognised by IOSH is that of Technician Safety Practitioner (TechSP). These are generally individuals who operate in lower risk environments or who report to more highly qualified practitioners. In some cases they are working towards the higher-level qualifications to gain IOSH membership. A TechSP holds a lower-level qualification and at least two years’ experience in OSH issues. Currently the IOSH membership framework is being re-structured and, as the eligibility requirements will focus solely on the higher competence level, the RSP category is likely to be replaced by ‘chartered’ membership status and the TechSP category will eventually be phased-out.

The stated role of the UK OSH practitioner: OSH practitioners are known by a variety of titles from health and safety officer or advisor, through to health and safety manager or director – reflecting varying demands and levels of responsibility. Practitioners may work in a variety of capacities e.g: providing in-house OSH services; or working for insurers, as self-employed consultants, as part of consultancy partnerships, and as regulators. Around five percent of IOSH members are inspection/enforcement officers, operating from a similar skill base as their counterparts in industry, but with additional competencies in law enforcement.

Expectations and requirements vary from sector to sector and from large to small organisations. As indicated above, the law requires employers to have access to competent OSH assistance, in order to help them comply with legal requirements and ensure that people are adequately protected from work-related hazards. Job advertisements and job descriptions also indicate that employers may seek OSH advisors to help them adopt best practice wherever this is reasonably practicable and that as modern OSH legislation is ‘goal-setting’, they may increasingly be involved in the holistic risk management process. At board-level, practitioners may be expected to advise on OSH strategy, policy formulation and implementation, and working with managers and team-leaders, to advise on measures to eliminate or minimise the risk of accidents and exposure to health hazards. Particular responsibilities specified in job descriptions may include: the development of procedures and safe systems of work; carrying out or supervising risk assessments and health surveillance programmes; the development and delivery of training; and conducting accident investigations, inspections and audits.

OSH is a multi-disciplined profession – the OSH practitioner role typically combines technical or scientific expertise; effective management techniques; and problem solving and communication skills. The OSH practitioner needs to work closely with other professionals such as occupational hygienists, occupational health practitioners, ergonomists, engineers (e.g. mechanical, chemical, electrical, structural), insurers, regulators and worker representatives. Practitioners have also been required to adopt broader roles encompassing additional responsibilities such as environment, quality, fire, security and risk management. In a 1998 ‘salaries and attitudes’ survey of IOSH members [7], the following levels of involvement were reported from the 1,168 respondents: 90.8% had at least slight involvement in environmental issues and

68.2% in quality issues. In the most recent of these surveys [8], of the 897 respondents, 80.9% reported involvement in the environment and 58.3% some involvement in quality and, though down on those of 1998, these are still high figures.

AIMS AND METHOD

Originally born under the auspices of the International Social Security Association (ISSA) and co-ordinated by Professor Andrew Hale, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, this international study transferred to the European Network of Occupational Safety and Health Practitioner Organisations (ENSHPO) in April/May 2003. A multinational survey into the role and tasks of OSH practitioners, the study currently involves 12 countries, with a further six agreeing to take part and three more showing interest in doing so. The aims are to collect comparative data by using a standard questionnaire, with the objectives of the study being:

- 1. To investigate the gap between the regulations and the actual work in practice done by safety practitioners;

- 2. To compare the work of safety professionals across countries to see whether the level and range of tasks that they carry out is comparable. This has an effect on mutual recognition of qualifications and for deciding which training experiences are transferable from one country to another;

- 3. To investigate whether there are different profiles within the safety profession, within or between countries, which need to be linked to different training requirements; and

- 4. To form a stronger basis for deriving learning objectives for the courses in each country and, eventually (if the study could be extended to the work of other professional groups), to group course members from different professions together for training on the basis of similarities in the competence that they require.

The questionnaire was designed by the ISSA working group and consists of 173 questions (193 variables) divided into 5 sections. Nearly all questions simply require appropriate responses to be ‘circled’ and the full questionnaire is estimated to take between 45 – 60 minutes to complete. The 5 sections are summarised as follows:

A. Organisation: questions include the type of organisation(s) respondents work for, how many employees are covered and in how many sites or countries, whether they work full-time and whether other health, safety or environmental professionals work in the same organisation. There is also an open question where respondents are invited to state what other work they may do.

B. Tasks: this section lists 83 tasks, which respondents mark according to how often they conduct them (weekly or more; monthly or quarterly; yearly or less; never yet, but it is part of my job; or not a part of my job). The tasks are divided into eight broad sections: (I) problem identification and analyses; (II) developing and implementing of solutions; (III) training, information and communication; (IV) inspection and research; (V) emergency procedures and settlement of damages;(VI) regulatory tasks; (VII) knowledge management; and (VIII) management andfinancial. There is also an opportunity to record tasks that do not appear in the list.

C. Types of hazards/issues: this section lists 31 types of hazard, which respondents mark according to how frequently they deal with them (weekly or more; monthly; yearly or less; present in company, but no task; or not present in company). Any additional hazards can be specified at the end.

D. Internal and external relations: this section lists 36 types of people, from both within and outside the organisation, with whom respondents might interact and respondents mark according to how often interaction occurs (weekly or more;

monthly; yearly or less; no contact yet, but is part of job; or contact is not part of my job). Any further contacts can be added at the end.

E. Personal information: this section asks questions about respondents’ age, gender, length of OSH experience in general and with current employer, education, safety qualifications and job title. General comments can be made at the end of this section about role, tasks or the questionnaire.

Further detail about the development, scope and progress of this study and a ‘master’ version of the questionnaire is provided in the conference paper titled: Surveying the Role and Tasks of the Safety Professional in Europe [3]. The version of the questionnaire used in the UK survey will be included in the full UK report [9].

The UK sample and analysis technique: the IOSH Registered Safety Practitioners (full corporate members) were selected as the UK study population. Corporate membership (MIOSH) is open to those holding an appropriate qualification coupled with a minimum three years' professional experience. Appropriate qualifications are:

- an accredited degree or diploma in OSH or a related discipline;

- Level 4 of the Vocational Qualifications for OSH Practice; or

- the National Examination Board in OSH (NEBOSH) Diploma Part 2 The Register of Safety Practitioners (RSP) lists Members of IOSH who have:

- been Corporate Members of the Institution for a minimum of one year;

- worked professionally within OSH for at least three years since achieving the academic requirements for Corporate status; and

- the competence and capability to undertake a wide range of activities.

Once accepted onto the register, CPD is mandatory and members have to submit records of their CPD activity on a regular basis in order to remain on the register.

The rationale for choosing this group was that it was believed most of them would be working in an OSH role, as they need to be active practitioners in order to maintain their CPD. TechSP category members were not included, as being in this category does not guarantee that an individual is working as an OSH practitioner. The suggestion from a recent IOSH survey [1] is that about a quarter of this group may not be solely involved in OSH practice, but have job titles/roles such as general management; safety representative; engineer; trainer; and planning supervisor. Further reasons for selecting RSPs as the sample group were that: they are known to work in variety of operational and strategic positions and across all employment sectors in the UK, so giving broad representation; and, being a 3,000-member group, they presented a good sample size. Questionnaires were sent to the 2,700 UK-based RSPs and the 300 RSPs permanently based outside the UK were excluded.

A total of 1,632 returns were received, a small number of which (11) were removed because they were from respondents in enforcement roles, leaving 1,621 completed questionnaires for analysis. The reason for removing/excluding enforcers from the study was because in some of the countries taking part, practitioners have different backgrounds and training to that of enforcers and it was felt that many regulatory questions would not apply to them and would make the questionnaire overly long and off-putting. All the questionnaires were completed as hard copies and returned in post- paid envelopes. The data was inputted onto an SPSS database (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) and frequencies and cross-tabulations generated, in line with the guideline issued by Professor Andrew Hale, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, the co-ordinator of this international study. During analysis of the UK data, whenever the missing frequency data is less than 5% (circa 80 cases) the SPSS ‘valid’ percentage has been used, but where it is more, the actual percentage has been

used.

Following the example given in The role and tasks of safety professionals in Norway and the Netherlands: A comparative study [14] the data has been coded according to the number of cases involved (A, B, C or D) and shaded the letters according to frequency (see table 6). The three frequency options of weekly or more, monthly or quarterly and yearly or less, were grouped together, as were the last two options of ‘never yet, but is part of my job’ and ‘not part of my job’. The lettering and shading indicate those tasks, hazards and contacts that are core to the work of the UK OSH practitioner and those that are not. The responses were grouped into three categories:

- tasks done, hazards dealt with or contacts made by 60% or more of the UK respondents

- those done, dealt with or made by between 30 and 60% of the respondents.

- those done, dealt with or made by less than 30% of the respondents

RESULTS

This section presents the survey analysis from the 1,621 completed questionnaires, representing a 60% response rate. Results are reported from all five parts of study, as follows: type of organisation; tasks; types of hazards/issues; internal and external relations; and personal information.

A.Organisation

Respondents were asked about the kind of organisation they worked for and over two- thirds reported working for industry/services, with nearly all of the remainder working as external consultants. As it is estimated that around 10% of the total IOSH membership are consultants (circa 2,500) the fact that nearly a third of this sample and by implication nearly a third of all RSPs are consultants (circa 1,000) is not unexpected.

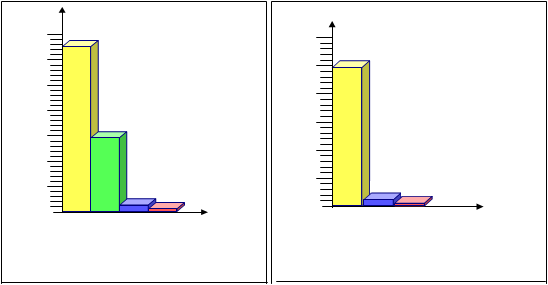

Figure 1. kind of organisation RSPs work for Figure 2. type of advisory body RSPs work for

|

|

70 65.9 3024.660 25 |

50

20

|

|

40 27.8 1530 1020 10 2 1.1 |

0

|

|

5 |

1.0 0.6

0

|

|

K ind of organis a tion |

Type of advisory body

Of the 425 (26% of sample group) working for an advisory body, 399 (24.6% of sample group) are consultants, 16 (1% of sample group) work for industry, national or regional advisory bodies and only 10 (0.6% of sample group) are in the fire service.

The questionnaire then asked about the main process of respondents’ industry/service and a total of 1106 respondents (68.2%) answered this question, the remainder working as consultants, for advisory bodies or insurers, or some other organisation. The following table highlights the eight main industry/service categories of the UK respondents, from the 28 possible options given in the questionnaire. ‘Other services’ is by far the largest category and includes all government, local authority and public services.

Table 2 – the eight main industry/service categories of the UK respondents

|

Industry |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Other services* |

269 |

16.6 |

|

Building and Construction |

164 |

10.1 |

|

Education |

100 |

6.2 |

|

Transport, post, comms & storage |

91 |

5.6 |

|

Health and welfare |

75 |

4.6 |

|

Chemicals |

48 |

3.0 |

|

Oil and coal |

48 |

3.0 |

|

Electricity, gas and water |

47 |

2.9 |

* In summary these are: local authority/public services (198 cases) and central government (28 cases) and other smaller groups such as facilities/maintenance, training/consultancy, industrial/business, prison and human resources.

Respondents were asked about a) the number of people covered by their advisory responsibilities and b) how many other advisors they worked with in their organisations. Of the responding UK OSH practitioners, 86% stated they had safety responsibilities covering more than 250 people and nearly two-thirds for more than 1,000. However, as it was possible that respondents working as consultants/advisory bodies, insurers or others, had answered question a) by aggregating the number people employed by all their client organisations, we excluded them (511 cases) in order to generate table 3. Of those responding UK OSH practitioners working in industry/services, 90% state they have safety responsibilities covering more than 250 people and nearly two-thirds for more than 1,000 people. In respect of the number of safety advisors they worked with in their organisations, 59.6% of this group work with less than 5 other safety advisors (17.2% with no others; 13% with one other; 29.4% with between 2 and 5 others); and 40.4% with more than five. Table 3 shows that 75% of those working in industry/services with no other safety advisors, cover more than 250 people and nearly a third cover more than a 1,000.

Table 3 – number of people covered: number of other safety advisors (industry/services only)

|

What is the total number of people covered by your safety (advisory) responsibilities? |

Do you work in your organisation with other safety advisors and if so how many? |

||||

|

No others |

1 other |

2-5 others |

> 5 others |

Totals |

|

|

0-50 |

6 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

16 |

|

51-100 |

11 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

24 |

|

101-250 |

25 |

13 |

17 |

12 |

68 |

|

251-500 |

34 |

23 |

33 |

28 |

118 |

|

501-1000 |

48 |

26 |

33 |

37 |

145 |

|

1001-5000 |

43 |

52 |

118 |

140 |

353 |

|

5000+ |

17 |

24 |

105 |

204 |

351 |

|

Totals |

189 |

143 |

322 |

443 |

1105 |

Re-combining the consultants/advisory bodies, insurers or others with industry/services, 61.4% of all respondents work with less than 5 other safety advisors in their organisations (22.9% with no others; 11.4% with one other; 27.1% with between 2 and 5 others) and 38.6% with more than five.

Table 4 – number of other safety advisors: kind of organisation

|

Do you work in your organisation with other safety advisors and if so how many? |

What kind of organisation do you work for? |

Table Total |

|||

|

Industry/ Services |

External consultant or advisory body |

Insurance Company |

Other (please specify) |

||

|

No others |

184 |

168 |

2 |

5 |

359 |

|

1 other |

139 |

33 |

5 |

1 |

178 |

|

2-5 others |

317 |

94 |

9 |

5 |

425 |

|

> 5 others |

425 |

157 |

16 |

6 |

604 |

|

Table Total |

1065 |

452 |

32 |

17 |

1566 |

Other organisational data includes the information that 90.3% of all respondents cover more than one site or company and 21.8% of these cover sites in more than one country. In respect to working hours, 85.4% of respondents work full-time, with a greater proportion of female RSP respondents (19.7%) working part-time than male (13.6%), and more than two-thirds of the part-time group aged over fifty. In answer to the question about ‘other’ work that is done besides safety, 17% (274) respondents gave 386 examples which were grouped into 32 broad categories, with some of the largest groups being: environmental management (45); teaching, training and development (39); business and risk management (29); facilities and maintenance (23); and health, hygiene and welfare (22).

The questionnaire asked whether there were other health, safety or environmental specialists working in respondents’ organisations. The UK data shows that respondents are more likely to work in an organisation that has an OH Nurse(s) than any other health, safety or environmental specialists. The next two types of specialist likely to work in respondents’ organisations were those for environment and fire. At the end of

the question, 15.4% of respondents indicated that there were a total of 328 ‘other’ specialists in their organisations, which were grouped into 35 categories, the main ones being: OSH advisors/consultants (44); trainers (25); and biologists, engineers and OH/hygiene specialists (each 19). Others included: environmental health officers and manual handling, microbiological/infection control, quality assurance/regulatory and risk specialists (each 12).

Table 5 – other H, S or E specialists in respondents’ organisations

|

Specialist |

Percentage |

|

Occupational physician |

28.4 % |

|

Occupational hygienist |

15.0 % |

|

Occupational health nurse |

40.2 % |

|

Work and organisation specialist |

7.2 % |

|

Ergonomist |

8.6 % |

|

Environmental specialist |

38.4 % |

|

Fire specialist |

27.8 % |

|

Health physicist/radiation expert |

12.8 % |

|

Other |

15.4 % |

B.Tasks

The largest section of the survey looked at the tasks performed by respondents and presented 83 variables, with scope for recording additional tasks. In order to establish the more and less commonly performed tasks i.e. those undertaken by the greatest/fewest number of respondents and carried out the most/least often, the data was coded as follows:

Table 6 – coding criteria for survey data

More than 80% of the responses in weekly, monthly, yearly or less.

A Meaning that less than 20% of the respondents do not deal with the task/hazard/relation in their job.

60% - 80% of the responses in weekly, monthly, yearly or less. Meaning

B that 40% to 20% of the respondents do not deal with the task/hazard/relation in their job.

30% - 60% of the responses in weekly, monthly, yearly or less. Meaning

C that 70% to 40% of the respondents do not deal with the task/hazard/relation in their job.

D

Shaded cells

Less than 30% of the responses in weekly, monthly, yearly or less. Meaning that more than 70% of the respondents do not deal with the task/hazard/relation in their job.

Denotes that more than 40% of the percentage is in weekly and monthly. Suggesting that the task is frequently done by 40% of the respondents.

Source: Ytrehus, 2003 [14]

Using this coding system, table 7 shows that the most commonly performed tasks from the UK data are mainly in the areas of developing and implementing of solutions and training, information and communication and that the least commonly performed tasks are mainly in the areas of emergency procedures, settlement of damages and regulatory tasks.

Table 7 – the frequency of tasks performed by UK respondents

|

Parts of Section B (Tasks) |

A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

D |

Total |

|

I Problem identification & analyses |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|||||

|

II Developing & implementing of solutions |

15 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

28 |

||

|

III Training, information & communication |

7 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

||

|

IV Inspection and research |

5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

|||

|

V Emergency procedures & settlement of damages |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

9 |

|||

|

VI Regulatory tasks |

3 |

6 |

9 |

|||||

|

VII Knowledge management |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|||

|

VIII Management & financial |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

|||

|

Total |

33 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

12 |

14 |

13 |

83 |

The significant numbers of tasks are indicated below:

- A total of 39 tasks (columns A and A) are performed by more than 80% of respondents, with 33 of these (column A) being done weekly or monthly by more than 40%.

- A total of 55 tasks (columns A, B, A and B) are performed by more than 60%, with 38 tasks (columns A, B and C) being done weekly or monthly by more than 40%.

- A total of only 13 tasks (column D) are performed by less than 30% of respondents

Those tasks that most UK respondents carry out and carry out frequently (weekly or monthly) are presented in table 8 below:

Table 8 – the 33 core tasks performed by UK respondents

|

I Problem identification and analyses |

|

|

Investigate & evaluate workplace or plant risks |

A |

|

Perform job safety analyses |

A |

|

Carry out risk analysis of projects, designs or activities |

A |

|

II Developing and implementing of solutions |

|

|

Prepare company policy related to safety of machines, processes or workplaces |

A |

|

Specify safety measures for machines, processes or workplaces |

A |

|

Develop/improve procedures for the safe use & maintenance of machines, processes or workplaces |

A |

|

Give instruction on the safe use and maintenance of machines, processes or workplaces |

A |

|

Check compliance with safety procedures for machines, processes or workplaces |

A |

|

Check compliance with safety procedures for dangerous materials |

A |

|

Monitor the correct use of PPE |

A |

|

Develop the company safety management system |

A |

|

Design performance indicators for the safety management system |

A |

|

Monitor the functioning of the safety management system |

A |

|

Propose improvements to the safety management system or parts of it |

A |

|

Assess the safety culture |

A |

|

Propose improvements to the safety culture |

A |

|

Lead or advise on organisational change to achieve improvement in safety performance |

A |

|

Check whether company policy or procedures conforms to legal rules and regulations |

A |

|

III Training, information and communication |

|

|

Inform/discuss with safety reps/committee about possible risks and safety measures |

A |

|

Inform/discuss with employees about possible risks and safety measures |

A |

|

Inform/discuss with first line supervisors about possible risks and safety measures |

A |

|

Inform/discuss with line managers about possible risks and safety measures |

A |

|

Inform/discuss with top management about possible risks and safety measures |

A |

|

Design safety training programmes or workshops |

A |

|

Give safety training programmes, courses or workshops |

A |

|

IV Inspection and research |

|

|

Investigate accidents or incidents |

A |

|

Make recommendations for improvement arising out of investigations |

A |

|

Conduct workplace inspections of physical prevention measures |

A |

|

Conduct workplace audits of safe behaviour |

A |

|

Conduct audits of the safety management system |

A |

|

VII Knowledge management |

|

|

Read professional safety literature |

A |

|

Attend courses or workshops about safety subjects |

A |

|

Exchange knowledge and practical experiences with colleagues at local or national level |

A |

The following table shows the core UK tasks that are dealt with on a weekly or monthly basis by the four main kinds of organisations respondents work for, showing the percentage of the particular group that are involved. Although insurers only account for a very small percentage of the study (2%), a larger proportion of them report frequently carrying out many of the core tasks, than the other three groups and in particular: develop/improve procedures for the safe use and maintenance of machines, processes or workplaces; check compliance with safety procedures for machines, processes or workplaces; propose improvements to the safety management system or parts of it; and check whether company policy or procedures conforms to legal rules and regulations (see shading in column 3, table 9 below).

In-house practitioners working for industry/services report broadly similar proportions of respondents carrying out core tasks to that reported by external consultants and advisory bodies. The latter, however, report higher proportions of respondents

performing: designing safety training programmes or workshops; and giving safety training programmes, courses or workshops (see shading in column 2, table below). Whilst the former report higher proportions engaging in: informing/discussing with safety representatives/committee; employees; first line supervisors; line managers; and top management (although insurers report higher proportions in this) about possible risks and safety measures; investigation of accidents or incidents; and making recommendations for improvement arising out of investigations (see shading in column 1, table 9 below).

Table 9 – the 33 core tasks performed by UK respondents, by organisation type

|

Core UK Tasks |

1) Industry |

2) External |

3) Insurer |

4) Other |

|

Investigate/evaluate workplace or plant risks |

88.1 |

86.5 |

100.0 |

82.4 |

|

Perform job safety analyses |

53.9 |

52.1 |

65.7 |

23.5 |

|

Risk analysis of projects, designs or activities |

55.3 |

52.4 |

62.5 |

52.9 |

|

Company policy, machines/processes/workplaces |

46.9 |

57.7 |

56.3 |

29.4 |

|

Specify safety measures, machines/processes/workplaces |

63.1 |

66.5 |

78.1 |

53.0 |

|

Develop procedures, machines/processes/ workplaces |

62.4 |

65.9 |

80.7 |

53.0 |

|

Give instruction, machines/processes/ workplaces |

52.5 |

55.6 |

68.7 |

52.9 |

|

Check compliance, machines/processes/ workplaces |

68.5 |

69.9 |

84.4 |

58.8 |

|

Check compliance, dangerous materials |

44.2 |

43.8 |

58.1 |

29.4 |

|

Monitor the correct use of PPE |

56.3 |

51.5 |

65.7 |

35.3 |

|

Develop the company safety management system (SMS) |

56.5 |

60.1 |

73.4 |

37.5 |

|

Design performance indicators for the SMS |

39.1 |

42.8 |

50.0 |

25.0 |

|

Monitor the functioning of the SMS |

68.5 |

61.1 |

81.2 |

58.8 |

|

Propose improvements to the SMS |

64.8 |

66.0 |

87.5 |

47.1 |

|

Assess the safety culture |

45.1 |

43.4 |

78.1 |

47.1 |

|

Propose improvements to the safety culture |

45.9 |

47.7 |

78.2 |

35.3 |

|

Lead/advise organisational change |

52.3 |

47.4 |

65.7 |

35.3 |

|

Check company policy conforms rules/regulations |

67.3 |

71.2 |

87.5 |

64.7 |

|

Inform/discuss with safety representatives/committee |

74.1 |

48.2 |

59.4 |

47.1 |

|

Inform/discuss with employees |

83.9 |

70.7 |

71.9 |

58.8 |

|

Inform/discuss with first line supervisors |

87.3 |

75.3 |

81.3 |

58.8 |

|

Inform/discuss with line managers |

89.7 |

78.2 |

84.4 |

58.8 |

|

Inform/discuss with top management |

80.1 |

72.6 |

87.5 |

52.9 |

|

Design safety training programmes/workshops |

44.1 |

61.0 |

54.9 |

29.4 |

|

Give safety training/courses/ workshops |

63.7 |

74.4 |

62.5 |

47.1 |

|

Investigate accidents or incidents |

76.3 |

46.8 |

62.5 |

52.9 |

|

Make recommendations from investigations |

81.4 |

52.2 |

59.4 |

64.7 |

|

Conduct workplace inspections |

73.7 |

68.5 |

81.2 |

52.9 |

|

Conduct workplace audits of safe behaviour |

47.5 |

48.7 |

59.4 |

41.2 |

|

Conduct audits of the SMS |

47.9 |

55.7 |

68.8 |

35.3 |

|

Read professional safety literature |

99.1 |

97.6 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Attend courses or workshops about safety subjects |

58.1 |

48.1 |

50.0 |

53.0 |

|

Exchange knowledge…local or national level |

84.6 |

79.3 |

81.3 |

88.2 |

|

Key: 1) Industry/services 2) External consultant/advisory body 3) Insurance company 4) Other |

||||

A number of respondents reported carrying out ‘other’ tasks (357 in response to the first ‘other’ option and 187 in response to the second), which they felt had not been covered by the questionnaire and analysis of this data is still being conducted and will be included in the final report [9].

C.Types of hazard/issues

Again this data has been coded in the same way as the tasks section, using the A, B, C, D categories and shading to indicate weekly or monthly by more than 40% of respondents. The following table lists the 22 core hazards for the UK respondents. Of these, 14 are dealt with by over 80% of UK respondents and also by more than 40% on a weekly or monthly basis. These are lighting; cold or heat; noise; toxic and carcinogenic substances; fire; electricity; machinery and installations; vehicles; human errors; falls; lifting; working posture; other physical workload; and VDUs. A further 8 are dealt with by over 60% of UK respondents. These are vibration; biological risks; other occupational disease; explosion; mental workload/stress; road/transport safety; accidents to patients or clients; and external safety. The last 4 of these are dealt with weekly or monthly by more than 40%. There were only 2 hazards dealt with by less than 30% (sustainability of production or products and product liability).

Table 10 – the 22 core hazards dealt with by UK respondents

|

Lighting |

A |

||

|

Cold or heat |

A |

||

|

Noise |

A |

||

|

Vibration |

B |

||

|

Toxic and carcinogenic substances |

A |

||

|

Biological risks |

B |

||

|

Other occupational disease |

B |

||

|

Fire |

A |

||

|

Explosion |

B |

||

|

Electricity |

A |

||

|

Machinery and installations |

A |

||

|

Vehicles |

A |

||

|

Human errors |

A |

||

|

Falls |

A |

||

|

Lifting |

A |

||

|

Working posture |

A |

||

|

Other physical workload |

A |

||

|

VDUs |

A |

||

|

Mental workload/Stress |

B |

||

|

Road/transport safety |

B |

||

|

Accidents to patients, passengers, students or other clients |

B |

||

|

External safety |

B |

||

The following table shows the core UK hazards that are dealt with on a weekly or monthly basis by the four main kinds of organisations respondents work for, showing the percentage of the particular group that are involved. As previously stated, although insurers only account for a very small percentage of the study (2%), a larger proportion of them report dealing frequently with all the core hazards, than the other three groups, in particular with noise, vibration, other occupational disease, fire, explosion, electricity, machinery and installations, vehicles, other physical workloads, VDUs, mental workload/stress, road/transport safety, accidents to patients/clients and external safety (see shading in column 3, table 11 below).

A slightly larger proportion of external consultants/advisory bodies report dealing frequently with many of the core hazards, than in-house industry/service practitioners (with the exception of biological risks, human errors, lifting, mental workload/stress and accidents to patients/clients) and in particular, noise and external safety (see shading in column 2, table 11 below).

Table 11 – the 22 core hazards dealt with by UK respondents, by organisation type

|

Core UK Hazards |

1) Industry |

2) External |

3) Insurer |

4) Other |

|

Lighting |

44.6 |

49.3 |

62.6 |

29.4 |

|

Cold or heat |

47.9 |

51.4 |

65.7 |

47.1 |

|

Noise |

46.2 |

62.3 |

71.9 |

35.3 |

|

Vibration |

32.6 |

41.9 |

59.4 |

17.7 |

|

Toxic & carcinogenic substances |

45.8 |

50.7 |

59.4 |

29.4 |

|

Biological risks |

30.9 |

27.6 |

37.5 |

23.5 |

|

Other occupational disease |

33.1 |

36.3 |

58.1 |

23.6 |

|

Fire |

67.3 |

69.9 |

87.5 |

35.3 |

|

Explosion |

24.1 |

35.0 |

59.4 |

11.8 |

|

Electricity |

60.9 |

68.9 |

87.5 |

47.1 |

|

Machinery and installations |

60.1 |

73.1 |

81.3 |

41.2 |

|

Vehicles |

60.4 |

68.3 |

84.4 |

47.0 |

|

Human errors |

75.7 |

73.8 |

84.4 |

58.8 |

|

Falls |

71.3 |

73.0 |

78.7 |

41.1 |

|

Lifting |

81.7 |

78.8 |

84.4 |

52.9 |

|

Working posture |

71.8 |

74.4 |

84.4 |

52.9 |

|

Other physical workload |

57.3 |

59.0 |

78.1 |

41.1 |

|

VDUs |

66.6 |

70.4 |

90.6 |

76.5 |

|

Mental workload/Stress |

49.6 |

46.7 |

68.8 |

35.2 |

|

Road/transport safety |

45.6 |

48.6 |

71.0 |

41.1 |

|

Accidents to patients, passengers, students, other clients |

42.4 |

39.4 |

65.6 |

58.8 |

|

External safety |

36.4 |

51.3 |

81.3 |

35.3 |

|

Key: 1) Industry/services 2) External consultant/advisory body 3) Insurance company 4) Other |

||||

There were 7.5% of respondents who identified ‘other’ hazards/issues they dealt with, that they felt were not covered by the questionnaire. These were grouped into 16 broad categories, which in summary were: dust/fumes/pollution (14); construction (12); public/non-employees (12); working space (11); slips, trips and falls (9);compliance/management systems (8); contractors (7); travel/off-site activity (6);major events/disasters (6); security (5); equipment (5); welfare (4); competence(education/training) (3); marine (3); food (3); and miscellaneous (17).

D.Internal and external relations

Table 12 below lists the 22 main internal/external relations for the UK respondents. Over 80% of UK respondents were in contact with 9 of these categories and more than 40% of them on a weekly or monthly basis, i.e. visitors; employees; line management; top management; technical/maintenance service; personnel department; professional association; safety officers of other organisations; and safety committees or safety representatives. Over 60% of UK respondents were in contact with a further 13 categories, i.e. occupational physician; lawyer; designer; environmental expert; government inspector; insurer; external safety consultant; educational establishment; local fire service; works council or equivalent; quality department; financial division; and trade union official. More than 40% were in contact with the last 4 of these weekly or monthly. Less than 30% of UK respondents were in contact with only 3 groups, these being work and organisation psychologist; policy maker in ministry; and inspector of (social) insurer.

Table 12 – the 22 core internal/external relations for UK respondents

|

Occupational physician |

B |

|

Visitors |

A |

|

Employees |

A |

|

Line management |

A |

|

Top management |

A |

|

Works council or equivalent |

B |

|

Quality department |

B |

|

Technical/maintenance service |

A |

|

Personnel department |

A |

|

Financial division |

B |

|

Lawyer |

B |

|

Designer |

B |

|

Environmental expert |

B |

|

Government inspector (national, local) |

A |

|

Professional association |

A |

|

Trade-union official (local or national) |

B |

|

Insurer |

B |

|

Safety officers of other organisations |

A |

|

Safety Committee or safety representative |

A |

|

External safety consultant |

B |

|

Educational establishment |

B |

|

Local fire service |

B |

There were 7.6% of respondents who listed ‘other’ internal/external relations that they had contact with. These were grouped into ten broad categories as follows: emergency services (31); public services (22); specialist institutions/professionals (17);clients/general public (14); contractors/consultants (12); education (10);trade/industry (6); government (4); training providers (4); and miscellaneous (3)

E.Personal information

Almost all UK respondents (99%) were experienced and had worked as safety professionals for more than 5 years and over a half (54.3%) had worked with their current employer for more than 5 years. All respondents were members of IOSH and membership of other professional associations related to safety was reported as follows: International Institute of Risk and Safety Management (21.6%); Institute of Risk Management (3.3%); British Occupational Hygiene Society (3.1%); The Association of Occupational Health Nurse Practitioners (0.4%); and ‘others’ (24.2%). The ‘others’ category included bodies such as Royal Society for the Promotion of Health (4.5%); Chartered Institute of Environmental Health (2.4%); Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (1.9%); and Institute of Safety in Technology and Research (1.5%).

Nearly all respondents (99%) had either university or further education levels of education. Appropriate adjustments were made to the dataset where there was obvious misinterpretation of this question, i.e. some respondents apparently believed the options referred only to full-time general education and did not include the process of gaining their ‘safety’ qualifications. This was evident when comparing individual responses to question E4 (education level) with their responses to question E5 (safety qualifications). The majority of the 1% at ‘secondary’ or ‘other’ education level are

older practitioners (aged >50 years), who may have been awarded membership prior to the existence of recognised safety qualifications, based on past experience and entry test. The UK data covering safety qualifications indicates that 1.7% have no such qualifications, though as this sample group are RSPs they must have some form of relevant qualification to be at this level. Almost half of the respondents (48.8%) have a safety qualification gained at university level; over half (57.1%) have a higher education diploma or equivalent; and 13.7% have a variety of other qualifications such as food safety, occupational hygiene and fire safety. It should also be noted that a number of those with university degrees also have higher education (HE) diplomas.

Cross-tabulating the OSH qualifications against the number of years in the profession shows the distribution of certain qualifications in relation to the years of experience as a practitioner (see table 13 below). Those who have been in the profession for more than 20 years are more likely to have ‘other safety qualifications’ than the other groups, with 18.3% having them compared to the 11.4% group average. This may be attributable to the fact that national safety qualifications were not available in the UK over twenty years ago. They are also more likely to have post-graduate diploma or certificates in OSH, with 29% having them compared to the group average of 26.4% and less likely to have the HE/National diploma or vocational qualification, with only 38.8% having them compared to the group average of 47.8%, indicating a preference in this group for accredited University courses in OSH.

Table 13 – OSH qualifications: years working as a safety professional

|

OSH Qualifications |

How many years working as a safety professional? |

Table Total |

|||

|

0-5 years(18 cases) |

6-10 years(378 cases) |

11-20 years(753 cases) |

> 20 years(442 cases) |

||

|

Masters or Research Degree in OSH |

2 |

42 |

79 |

46 |

169 |

|

P-grad Diploma or Certificate in OSH |

4 |

110 |

240 |

142 |

496 |

|

BSc or BSc (Hons) in OSH |

1 |

29 |

50 |

21 |

101 |

|

HE Dip / S/NVQ4 in OSH / NEBOSH Dip2 |

11 |

239 |

458 |

189 |

897 |

|

Other safety qualification |

2 |

33 |

90 |

89 |

214 |

|

Table Total |

20 |

453 |

917 |

487 |

1877 |

Respondents were asked to indicate the job title of their safety function and these were grouped into 6 main categories as follows:

- Director – included employed or selfemployed directors

- Senior manager – included chiefs or heads

- Manager – included safety or safety and health in their title (401); general management (31); and risk management only (34)

- Advisor/officer/coordinator – included advisors (389); officers (144); and co ordinators (17)

- Other – included respondents who described where they worked, what they did or stated their qualifications

The overall breakdown broadly indicated that 39% were in the director/senior manager/manager groups; 53% in the advisor/consultant groups; and 8% did not specify. It was also the case that 16% (263) of respondents had job titles that included 'environment' (216), 'quality' (7) or both (40). Additionally, a number of respondent job titles included ‘risk’ (79); ‘fire’ (10); and ‘security’ (9).

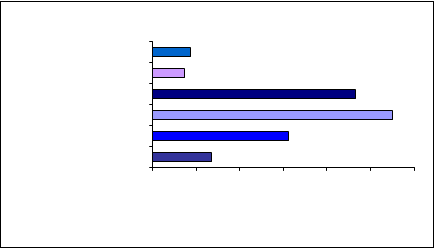

Figure 3 – job title groupings of UK respondents

Director 87

|

|

Senior Manager 73 Manager Advisor/ Officer/ Co-ordinator |

466550

Consultant311

Other1340 100 200 300 400 500 600

No. of respondents

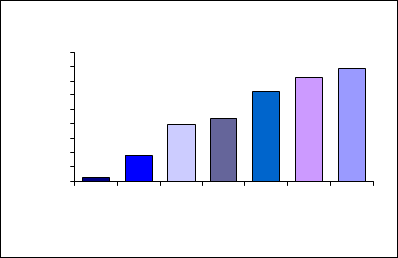

The gender of the UK respondents was 89% male and 11% female and the age distribution can be seen in figure 4 below, indicating that only 19% were less than 40 years old and that nearly half were over 50 years old.

Figure 4 – age of respondents

450400

35030025020015010050 150

196 221

92

310

363

39325-30yrs31-35yrs36-40yrs41-45yrs46-50yrs51-55yrs55+yrs

Age

Table 14 below gives a snapshot of age distribution and indicates that a minimum 34.8% of respondents to the question (the 552 highlighted in grey below) were over 30 years of age when they entered the profession, so were unlikely to have entered ‘safety’ as their first career.

Table 14 – age of respondent: years working as a safety professional

|

What is your age? |

How many years working as a safety professional? |

Total |

|||

|

0-5 years |

6-10 years |

11-20 years |

> 20 years |

||

|

25-30 years31-35 years36-40 years41-45 years46-50 years51-55 years55 years or older Total |

120563118 |

12597766685340375 |

231116124168172138751 |

0012567135213441 |

15921942203093633921585 |

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

All the data generated by this survey is self-reported and subjective and most of the questions rely upon the respondent to remember and estimate how frequently they perform a task, deal with a hazard or make internal/external contacts. However, as the survey was anonymous, received a good response rate and provided the options of reporting ‘never yet…’ or ‘not part of my job’ or specifying ‘other’ if the given questionnaire options were felt insufficient, it is believed that the overall picture will be representative of this sample group. The UK sample consisted of those from the highest IOSH competence level (RSPs) and so respondents’ qualifications were necessarily of a higher level, as this is an entry requirement for the register. Again, because the sample group consisted of RSPs, the core tasks, hazards and contacts were large in number and broad in range, including management and strategic issues.

The relatively low level of female RSP respondents (male/female ratio 8:1) possibly reflects the national participation in certain jobs perceived to be ‘technical’, such as skilled trades (male/female ratio 12:1) and process, plant and machine operatives (male/female ratio 5:1), which if combined give a ratio of 8.5:1. However, it is interesting to note that in the national statistics for the categories ‘professional occupations’ and ‘associate professional and technical’, there are similar proportions of males and females [11] and the overall IOSH membership does indicate a higher female percentage, with a male/female ratio of 5:1. In respect of age distribution, the sample shows less than 1% of respondents were under thirty years of age, 20% under forty and that nearly half were over fifty. This is not unexpected as the sample group were the more experienced and more highly qualified amongst the membership. Also, at least 34.8% of respondents were over thirty years of age when they entered the profession, indicating that they were unlikely to have entered ‘safety’ as their first career.

As expected, generally the larger the organisation, the more safety professionals they employed, however, it is surprising to note that 75% (142) of those working as sole advisors in industry/services, actually cover more than 250 people, with nearly a third covering more than a 1,000, and 9% (17) covering more than 5,000. Mindful of the requirements of Council Directive 89/391/EEC [2], article 7, for employers to ensure competent ‘protective and preventive services’ and that “…the workers designated and the external services or persons consulted must be sufficient in number…”, this would seem to be an area requiring further research. Whilst it is accepted that low hazard organisations may require fewer advisors than higher hazard organisations, the

number of employees covered and the logistics involved are also key factors. The survey also showed 86% of responding RSPs reported that their safety responsibilities covered more than 250 people and that only 14% covered less than 250 people. As there are 3.7 million small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the UK and nearly half the UK workforce is employed by them, this apparent low level of access to competent advice has obvious implications.

It is encouraging to note that the UK core tasks include not only the more traditional tasks, but also significant coverage of management systems, safety culture, safe behaviour issues and assessment of designs. In addition, in-house practitioners report high levels of activity with regard to informing/discussing with safety representatives/committee; employees; first line supervisors; line managers; and top management about possible risks and safety measures; investigation of accidents or incidents; and making recommendations for improvement arising out of investigations. All of these may have implications for guidance material, training syllabi and CPD, which will need to support competence in these areas, particularly in accident investigation techniques and communication skills. It is perhaps not unexpected that five of the UK regulators priority areas are identified among the UK respondents’ core hazards i.e. mental workload/stress; VDUs/working posture/vibration (causes of MSD); falls (including falls on the level and falls from height); vehicles and road/transport safety. Again all of these may have implications for education/training syllabi and CPD, which will need to support competence in assessing and managing these issues.

The study confirms that RSPs work in a variety of positions with have a broad range of responsibilities. The overall breakdown broadly indicates that 39% were in the director/senior manager/manager groups and 53% in the advisor/consultant groups. In respect to the breadth of the RSP role: there are 16% (263) of respondents with job titles that include 'environment' (216), 'quality' (7) or both (40). The diversity of the roles is perhaps further indicated by the frequent respondent use of the ‘other’ option, in order to describe elements that they felt were not covered by the questionnaire variables. As part of their responses 17% (274) of respondents listed 386 examples of other work they carry out in addition to their safety responsibilities; 7.5% (121) gave examples of other hazards they deal with, 22% (357) of other tasks they perform and 7.6% (123) of other contacts they make, in addition to the options on the questionnaire. In order to support RSPs in achieving and maintaining competence for their challenging and multi-skilled role, appropriate training and CPD opportunities need to be available to cover all the significant tasks, hazards and interrelationships outlined in the RSPs’ responses.

In summary, this study has provided a benchmark position on the role and tasks of the RSP population of IOSH. While the study has established the diversity and complexity of the role, it poses some searching questions worthy of further research – how to determine what is a sufficient number of competent practitioners for any given organisation; why are females less likely to be attracted into the OSH profession than males; what are the advantages and disadvantages to a profession of mature entrants; how can SME access to competent advice be improved; and what education/training and CPD is required to support the RSP role? Addressing these and other issues raised by this initial study will contribute to the development and standing of the profession.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Professor Andrew Hale, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, for his invitation to participate in this important study and his subsequent guidance; Dr Luise Vassie, Leicester University, UK, for her advice and support; and especially, his IOSH Technical Affairs colleagues Andrea Alexander, Mary Ogungbeje and Murray Clark for all their hard work in processing the large quantity of data. He also extends his thanks to all the RSPs who took the time to complete and return the questionnaires for their invaluable input.

REFERENCES

- 1. Clark M and Jones R (2003), Professionals in partnership: A survey exploring the selfperceived effects of IOSH guidance on the occupational health activity of Technician Safety Practitioners (p.8), Wigston: IOSH http://www.iosh.co.uk/files/technical/TIPiPsurvey030912%2Epdf

- 2. EC (1989), Council Directive 89/391/EEC of 12 June 1989 on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work, L183, 29 June 1989, Brussels, Belgium: Official Journal of the European Communities. http://europa.eu.int/scadplus/leg/en/cha/c11113.htm

- 3. Hale A R and Ytrehus I (2004), Surveying the role and tasks of the safety professional in Europe, Paper to the 3rd International Conference on Occupational Risk Prevention, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2 – 5 June 2004.

- 4. Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, SI 1974/1439, London: HMSO.

- 5. HSC (2002), The health and safety system in Great Britain, Sudbury: HSE Books.

- 6. HSE (1998), Successful health and safety management. HSG65, Sudbury: HSE Books.

7. IOSH, Macmillan Davies Hodes (1998), “What is your worth? The state of the profession”, The Safety and Health Practitioner, June 1998, Vol. 16, No. 6, pp. 60

- 61

- 8. IOSH, Macmillan Davies Hodes (2003), “Getting your opinion”, The Safety and Health Practitioner, July 2003, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 55 57

- 9. Jones R (2004), Survey into the role and tasks of OSH practitioners in the UK, [to be published by IOSH]

- 10. Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999, SI 1999/3242, London: HMSO.

- 11. Office for National Statistics (2003), UK 2004 The Official Yearbook of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, London: The Stationery Office.

- 12. Packman R (1968), “The historical background of factory law” in A Guide to Industrial Safety and Health, Longmans, London: Green and Co Ltd, pp. 113.

- 13. Robens (1972), Safety and Health at Work: Report of the Committee 197072 Cmnd. 5034, London: HMSO.

- 14. Ytrehus I (2003), The role and tasks of safety professionals in Norway and the Netherlands: A comparative study, Trondheim, Norway: Norwegian University of Technology and Science, Master thesis.

Papers relacionados