Introduction

Violence at work first was identified as an emerging occupational health and safety risk in the 1990s. A report concerning prevention of workplace violence, prepared for the European Commission, was published in 1997. In it, violent incidents were defined as “Incidents where persons are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health” [10]. This definition covers both direct violence, in which workers themselves are threatened or assaulted, and indirect violence, in which workers’ family members or friends are threatened or assaulted [10]. Intentionality of the act is part the definition of violence used by the World Health Organization (WHO), although it notes that intentionality does not necessarily mean that the intent is to cause damage [2]. Despite all efforts, workplace violence still is a burning issue in contemporary working life, causing psychological harm, injury, or even death, not to mention economic loss. High-risk occupations, such as healthcare, are especially prone to violence in the workplace.

Analysis of the Finnish national accident-statistics database shows that work accidents related to violence have increased, and their number is highest in medical and nursing occupations. On the basis of accident descriptions, it appears that incidents usually involved being restrained, hit, or assaulted. In medical and nursing occupations, the incident rate was 3.2 per 1000 employees in 2006. In the same year, the average rate of violent incidents at work for all employees was 0.93 [1]. In 2007, a questionnaire survey was carried out by Statistics Finland to investigate physical violence or threats of it at work or on the way to or from work. For medical and nursing occupations, the results indicated that 18.3% had experienced physical violence or threats of it in the previous 12 months. The average for all occupations was 4% [4].

In organizations at high risk for violence at work, it is crucial that violence prevention be integrated into occupational health and safety management. In addition, the systematic approach based on the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) methodology, referred to in OHSAS 18001 (Occupational health and safety management systems. Requirements), must be followed to continually improve occupational health and safety performance [3].

A Finnish research project, carried out from 1997‒2000, developed a systematic approach that stressed continual improvement and methods for assessing and managing the risk of violence at work. The KAURIS guidebook, published in 2001, supported workplaces in preventing workplace violence. The latest version of the guidebook, with improved applicability for various sectors, was published in 2009. It contains tools for identifying problems at work and information sheets to help plan safety improvements. These information sheets cover technical and organizational measures, procedures, guidelines, training, monitoring, reporting, and analyzing incidents, and post-incident support for victims. A Swedish translation of the KAURIS guidebook was published in 2013 [5,6].

In Finland, prevention of workplace violence is considered separately in legislation. Research on workplace violence has provided background information for legislative reform. According to the Finnish Occupational Safety and Health Act, which took effect in early 2003, in jobs at high risk for violence, the work and working conditions must minimize the threat and incidents of violence. There must be safety arrangements and equipment that would enable calling for help, safety procedures that would help control threatening situations, and practices that would prevent or contain violent incidents. In addition, safety arrangements and equipment function must be checked as needed [7].

From 2010 to 2012, a research project at the Center for Safety Management and Engineering (CSME), Tampere University of Technology (TUT) studied violence prevention in healthcare environments. The Finnish Work Environment Fund provided principal financial support for the project, which was conducted between May 1, 2010 and January 31, 2012. Study results can be found on the fund’s web site [8,9]. The research project’s main objective was to improve violence prevention in healthcare workplaces. Other objectives were to produce information on the current status of workplace violence in healthcare facilities and to develop a model to prevent and control workplace violence, especially in hospitals. This paper focuses on the model, which can help to integrate violence prevention more effectively into health and safety management.

Methodology

Gathering data on the current situation

First, the CSME research project conducted a literature review to gather information on workplace violence and its prevention. In addition, interviews and questionnaire surveys were conducted to gather data on the current situation in 15 hospital districts in Finland. More detailed data was gathered by interviews, questionnaires, and observation in selected, somatic healthcare units in two of the hospital districts. All material provided background for developing the model for preventing and controlling workplace violence.

Model development

The model’s first draft described its preliminary structure and content. The draft was presented to a steering group of the project, consisting of members from healthcare organizations, industrial safety authorities, and other groups. Group members’ comments and meeting discussions were taken into account as development of the model continued in close collaboration with the steering group, which was asked to comment on each version. Development acknowledged the necessity of complying with legislation and occupational health and safety management systems (OHSAS 18001), and special attention was paid to identifying responsibilities and tasks at different levels of hospital management.

In addition, the model was presented to participants in various seminars arranged in one hospital district. In some of these seminars, workers and those at all levels of management were represented and participants were asked for comments and proposals on the model’s current version. In addition, comments also were gathered during discussions with one safety manager who was a member of the steering group representing another hospital district.

Results

Current situation in healthcare

According to the results, workplace violence was experienced as a problem in 11 of 15 hospital districts. Violent incidents seemed to have increased in almost all of the 15 districts, and there was a perception that incidents had become more arbitrary and more difficult to anticipate. The perpetrator was most often a patient acting against personnel, but escorts and patients’ family members sometimes became violent. In general, violent behavior was seen to be related to intoxicants, such as alcohol and drugs; illnesses; dissatisfaction with care; and long waits. Although some efforts had been made to prevent and control violence, additional action was needed to improve safety.

Toward violence-free work environments

In the quest to prevent and control violence, one important goal is violence-free hospital environments, ensuring the safety and well-being of patients and staff. The central role of safety management and leadership must be emphasized, with a safety culture, a safety climate, and values contributing in the background. Society controls safety through legislation that sets requirements for organizations. In addition, organizations’ operating environments are affected by such factors as prevailing social order (Figure 1).

As Figure 1 illustrates, several areas of safety and security affect prevention and control of violence at work. In addition to occupational health and safety, crime prevention, premises security, information security, and safety of the organization’s activities, such as patient safety, are involved.

Figure 1. Factors affecting violence prevention in hospitals [8].

Preventing and controlling workplace violence

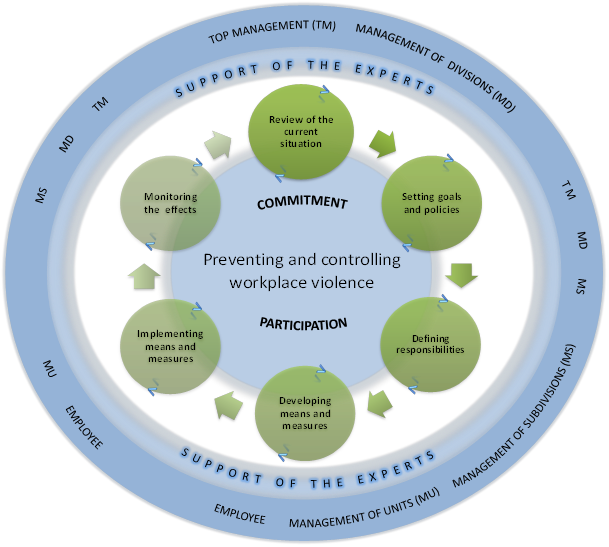

To prevent and control workplace violence, a systematic approach must be implemented, starting with review of the current situation and continuing with setting goals and policies, defining responsibilities, developing means and measures, implementing them, and monitoring the effects (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The phases of violence prevention and control in hospitals [8].

Preventing and controlling workplace violence requires commitment and participation from employees and managers at all levels. Internal and external experts can support the improvement process. In reviewing the current situation, important questions include what kind of violent situations occur in the organization, how common they are, and how serious the consequences could be. In addition, it is important to determine how well the organization has prepared for violent situations; what kind of solutions, technical measures, and devices are in use at the moment; how the organization is handling personnel training and other necessary activities; and what improvements still could be made. The KAURIS guidebook can be used to identify problems and help plan measures to improve safety [5,6].

Responsibilities and tasks at various levels of management

According to interviews and observation, various parties’ responsibilities and tasks were found to be unclear. Therefore, responsibilities and tasks were defined as a part of the model. Various management levels were defined, including top management, middle management (management of divisions and subdivisions), and unit management (foremen). In addition, the model defined the responsibilities and tasks of employees, internal experts, and occupational healthcare units.

Top management has principal responsibility for occupational health and safety, including violence prevention and, therefore, should demonstrate commitment and responsibility in its practices. Top management should be aware of the overall situation concerning hazards, risks, and past violence in the hospital. Top management also is in a key position to provide necessary resources, plan prevention, and set goals.

Middle management has the responsibility to prevent violence at its own level. One important task at the level of division manager is reporting to top management the necessary information, initiatives, and proposals for improvement. Subdivision managers must collaborate with internal and external experts and support the units’ foremen and employees as needed.

Foremen play an important role in violence prevention and control because they are the management level closest to those who work with patients and in other types of jobs where problems usually appear. Foremen should be responsible for violence prevention and control in their own units and for associated tasks, such as training and motivating workers and providing feedback. It is also a foreman’s responsibility to provide post-incident support to victims as needed. This can be done for example in collaboration with the occupational healthcare unit.

Workers face various demanding situations in the workplace, and they should be able to behave professionally even in difficult, provoking situations. In addition, workers are responsible for following the orders and instructions given by the employer and policies to report hazardous situations. The study noted deficiencies in many hospital districts related to reporting violent situations.

The important task of internal experts and occupational healthcare unit is to support the organization in its efforts to prevent and control violence. Their help is needed in different phases of the improvement process, such as monitoring violent incidents and developing measures to improve safety.

Discussion

Study results indicate that workplace violence is a problem and that violent incidents seem to have increased in most of the hospital districts in the study. This is consistent with previous studies that have identified healthcare work as an occupation at high risk for violence at work [1,4]. In addition, the study recognized a clear need for improved violence prevention and control in the hospital districts.

The model for workplace violence prevention and control developed in this study helps hospitals improve safety systematically and more effectively integrate violence prevention as part of their health and safety management. For example, a hospital can compare the model’s list of responsibilities and tasks for various management levels with present practices and use the results to improve practices. All personnel must be trained in their responsibilities and tasks. In addition, discussing the responsibilities and tasks of various parties while implementing the model may increase general understanding among groups in the hospital organization, thus improving safety culture. Safety culture is very important in a workplace in which various groups and professions collaborate in their daily work.

Depending on the needs of the hospital organization and its units, other methods, such as the KAURIS guidebook, can be used to help identify problems and plan preventive measures [5,6]. Monitoring results is an essential part of the process, aimed at continual improvement. Active reporting of violent incidents should be encouraged throughout the organization. However, it must be taken into consideration that the violent situation can be a very sensitive issue for the victim and may lead to self-accusation. Therefore, it is important to emphasize learning from violent incidents, continual improvement of safety in the organization, and avoidance of a blame culture.

The model for workplace violence prevention and control was developed in close collaboration with the steering group of the project consisting of members from healthcare, industrial safety authorities, and other groups. The model was developed in compliance with legislation and occupational health and safety management systems. Background information was gathered from 15 hospital districts, two of which were examined in more detail, providing better understanding of violence and its prevention in healthcare. In addition, one of the hospital districts actively participated in developing the model. Information on actual situations and collaboration with healthcare experts and hospital staff improved the model’s validity.

Information on the model has been disseminated through a press release, at the closing seminar of the project, at other seminars, and in published articles. The model is publicly available to all interested parties on the web site of the Finnish Work Environment Fund. Healthcare personnel have shown a great deal of interest in study results. However, the study’s actual effects on safety in healthcare workplaces depends on how actively the model is used in practice.

Conclusions

The model developed in this study provide a systematic approach to prevent and control workplace violence. This approach, which aims for continual improvement, starts with reviewing the current situation and continues with setting goals and policies, defining responsibilities, developing means and measures, implementing them, and monitoring the results. The model emphasizes integrating violence prevention and control into health and safety management. The model defines responsibilities and tasks for managers at various levels, employees, and internal experts.

The model is most applicable in hospitals, but it may provide useful information for other healthcare organizations. In hospitals, the model can be used to integrate violence prevention and control more effectively into health and safety management. Awareness of the violence problem is an important first step for beginning the improvement process. Although top management is in a key position to prevent and control violence, commitment and participation of the whole staff are needed in the continual improvement process.

Violence at work is a complex problem that has gained attention in the last generation, especially in high-risk occupations, such as healthcare. The present study focused on violence prevention and control in hospitals. Although no simple solutions exist, good results can be achieved with a systematic approach and effective health and safety management.

Acknowledgement

Financial support from the Finnish Work Environment Fund is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are thankful for active participation of the hospital districts, of which two were examined in more detail and one contributed time to model development. In addition, the active collaboration and expertise of the steering group is greatly appreciated.

References

- 1. Hintikka, N. & Saarela, K.L. (2010) Accidents at work related to violence Analysis of Finnish national accidet statistics database. Safety Science 48, 517525.

- 2. Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B. & Lozano, R. (Eds.) (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization, Geneva, 372 p.

- 3. OHSAS 18001: 2007. Occupational health and safety management systems. Requirements, 54 p.

- 4. Piispa, M. & Hulkko, L. (2010) Työväkivallan riskiammatit (Highrisk occupations related to violence at work). Työturvallisuuskeskuksen raporttisarja 1/2010, 19 p. (in Finnish)

- 5. Saarela, K.L. (2008) El método KAURIS. Evaluación y gestión del riesgo de violencia en el trabajo (KAURIS method for assessment and management of risk of violence at work). Seguridad y Medio Ambiente. 28, 111, 1620. (Spanish with English summary)

- 6. Saarela, K.L.; Isotalus, N.; Salminen, S.; Vartia, M. & Leino, T. (2009) KAURIS –kartoita uhkaavat työväkivaltariskit. Menetelmä työväkivaltariskien kartoitukseen ja hallintaan. (Guidebook on the KAURIS method for assessment and management of risk of violence at work) Työterveyslaitos (FIOH), Helsinki, 72 p. (in Finnish)

- 7. Työturvallisuuslaki 738/2002. (Occupational Safety and Health Act) Available from Finlex.fi (in Finnish with unofficial english translation).

- 8. Vasara, J.; Pulkkinen, J.; & Anttila, S. (2012) Työväkivallan ennaltaehkäisy ja hallinta sairaalassa. Organisaatiotasojen vastuut ja tehtävät turvallisuusjohtamisessa. (The model for workplace violence prevention and control in hospitals), 29 p. Tampere University of Technology, (in Finnish). Available from: http://www.tsr.fi/tutkimustietoa/tataontutkittu/hanke/?h=110123&n=aineisto

- 9. Vasara, J.; Pulkkinen, J.; & Anttila, S. (2012) The final report of the project: Työväkivallan hallinta turvallisuusjohtamisen osana terveydenhuollossa (Violence control as a part of health and safety management in healthcare), 23 p. Tampere University of Technology, (in Finnish). Available from: http://www.tsr.fi/tutkimustietoa/tataontutkittu/hanke/?h=110123&n=aineisto

- 10. Wynne, R; Clarkin, N.; Cox, T.; Griffits, A. (1997) Guidance on the prevention of violence at work. European Commission, DG V, Luxembourg, 51 p.

Papers relacionados