Introduction

The occupational risk of musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) in office workers is mainly related to the physical characteristics of the workplace and tasks involving computers; problem areas can include inadequate postures or excessive time of use of the mouse and keyboard. According to several studies [1-6], interventions such as the availability of ergonomic products, postural education or a combination of both can reduce the risk of MSD related to computer use by up to 50%. However, study heterogeneity leads to inconclusive data, and more research on the subject is required to determine the effectiveness of such interventions [1, 7-11].

At the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB), the analysis of different technical interventions and the conclusions of occupational health surveillance performed by the Prevention Service have determined a back pain prevalence of more than 40% among the University’s staff. This figure is considered high in comparison to the prevalence of back pain in Europe. According to the European Agency for Occupational Safety and Health, 30% of European workers (11 million) suffer back pain [12, 13].

As the UIB has a staff of approximately 2,000 workers, a significant population at the University was supposed to be affected by back pain, requiring an intervention aimed at preventing and correcting the occurrence of pain in different areas of the back, mainly related to sedentary work in front of computer screens, which is the most common type of task performed by the staff.

The Prevention Service of the UIB designed an ergonomic intervention specifically aimed to the prevention of back pain at work through the enhancement of monitoring of the workplace ergonomic conditions, the change in postural habits and physical activity and the acquisition of postural awareness by workers. The purpose of this intervention was to offer employees the tools to improve and maintain their health, thus making them responsible for the prevention of back pain.

Using different actions, the objective of this intervention was to improve the ergonomic conditions and postural habits of these workers and change their sedentary lifestyle, both at work and at daily life activities. These efforts were made in order to improve or maintain the workers’ health and to prevent occupational injuries, mainly back pain.

Methods

Ergonomic intervention

The designed ergonomic intervention included different actions, all of them coordinated and focused on the previously described common objective:

- Ergonomic analysis of the workplaces and correction of the deficiencies found. Prevention technicians reviewed risk assessments of the staff. The ergonomic evaluation of tasks in front of a computer screen was performed according to the method of the Spanish Ministry of Health [14]. The questionnaire collects information about the room configuration (the surface area per person, locations of the tables, computer screens, fluorescent lights and other devices, the presence of window blinds, furniture colours, etc.), the workplace layout (accessibility, space for mobility of the arms, trunk and legs, distance between the eyes and screen, etc.), the work equipment and its location (desk height and width, backrest inclination, chair height, need for a footrest or forearm support, keyboard inclination and location, screen height, inclination and orientation, etc.), the environmental aspects(possibility of temperature regulation, degree of comfort in summer and winter, air renewal, noise, appropriate level of lighting based on work performed, the existence of natural light, etc.) and the physical and postural load (if the position adopted at work is correct or incorrect).

- Course on postural education and back care. The course objectives for the workers were as follows:

- To become aware of one’s own posture and usual gestures;

- To correct harmful postural habits;

- To identify ergonomic problems of their own workplace;

- To adapt equipment to their needs and characteristics;

- To incorporate breaks and changes in activity suitable to the working day.

- Promotion of physical activity. The use of exercises and stretches during the workday was promoted through the installation of a computer application (ErgoUIB computer application) designed ad hoc to serve as a guide and reminder for performing the activities. The ErgoUIB application made two announcements during the day at selected times. It offered four exercises or stretches guided by video that the worker should perform at that moment; this activity also served as a task break. Additionally, workers were encouraged to perform physical activities outside of working hours, mainly sports that strengthen the trunk musculature in a balanced manner.

Participants

Study participants were support and administration staff of the University who worked at a computer workstation. Participants included 57 women and 13 men whose ages ranged from 25 to 64 years. All participants were asked to sign an informed consent form. The study was previously approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of the Balearic Islands.

Most of the participants worked in large rooms with several computer workstations around the room. Some worked in shared offices (2 to 3 workers per room), and only a few worked in private offices. All the participants worked at computer workstations with adjustable office chairs, adjustable computer screens and variable lighting conditions that may include natural light from windows.

Study design

A modified randomized experimental design was used. Participants were divided into the following groups: group 1 received the complete ergonomic intervention (ErgoUIB programme), group 2 received only the course, group 3 received only the computer application, and group 4 (control group) did not receive any action.

In order to prevent contamination of the intervention, participants from the same department (that is, sharing an office or a large room) were assigned to the same group. This disproportion was then corrected by assigning similar size departments to the remaining groups.

Procedure

Once the participants signed the informed consent, demographic, work-related and health-related personal data were collected before randomization, using a specially designed questionnaire. Participants were asked about the frequency of use of certain working postures (never, occasionally, regularly, usually, always): forward position (fig.1a), forward position away from backrest (fig.1b), upright position (fig.1c) and reclined or rear-tilt position (fig. 1d).

|

a |

b |

c |

d |

Figure 1. Working positions

All participants received the ergonomic analysis of the workplace, and modification of any improper working condition.

Participants in group 4 (control group) did not received any other action, though they were informed about the availability of the ErgoUIB computer application and website.

Participants in group 1 received a four weeks course on postural education and back care, and a reminder session once a month for the next three months. They also had the ErgoUIB computer application installed in their computer, and they were instructed on how it worked, and enhanced to use it.

Participants in group 2 received only the course, in the same conditions as group 1 participants.

Participants in group 3 only had the ErgoUIB computer application installed in their computer, in the same conditions as group 1 participants.

Data collection instruments

Different tools were used to obtain data at different times:

- Demographic, work-related personal data (postural habits at work, working conditions, break frequency and duration) and health-related personal data (physical activity, work-related musculoskeletal pain) were collected using a specially designed questionnaire.

- Data relating to improper working conditions were obtained from in-situ ergonomic analysis, as well as the corrective measures taken in each case.

- During the intervention, there was an individualised audit of computer application use (for groups 1 and 3).

- After the intervention, another interview was performed, and new data were obtained from the same specially designed questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the postural habits was performed to test the postural habits of each group before and after intervention. The effects of the intervention on all the experimental groups have been examined in comparison with control group. Each group was also analysed separately.

Results

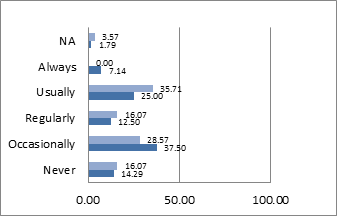

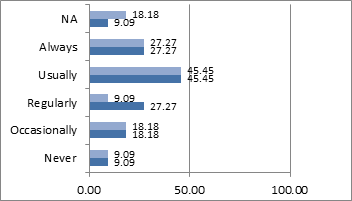

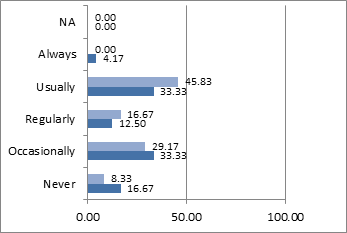

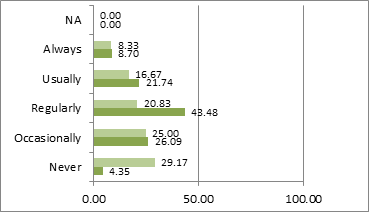

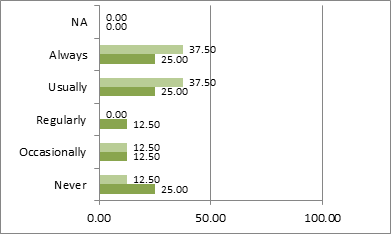

Results showed that the postural habits (i.e. the frequency of use of each working posture) changed throughout the experiment among experimental group participants compared to control group, as can be seen in figure 2 and 3.

Regarding experimental groups:

Forward position was "usually" used by fewer participants after the experiment , while few more participants used it "occasionally".

Forward position away from backrest was used "usually" by less people. The number of participants that used this position "occasionally" increased after the experiment.

Upright position use was clearly increased.

Reclined position use showed little changes, showing that few people that did not use this position before the intervention started to use it "occasionally".

|

Forward position |

Forward position away from backrest |

|

|

|

|

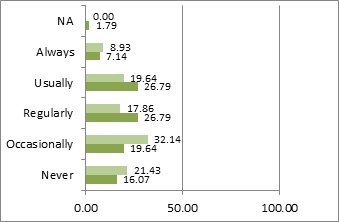

Upright position |

Reclined position |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Frequency position use reported by experimental group participants (1, 2 and 3) before and after intervention (colours lighter and darker, respectively).

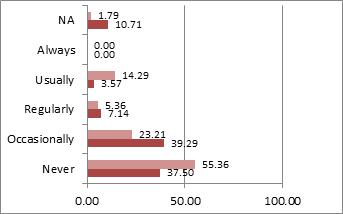

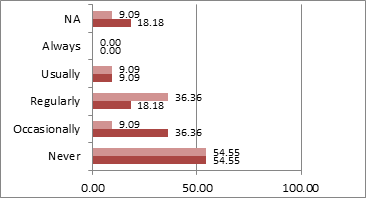

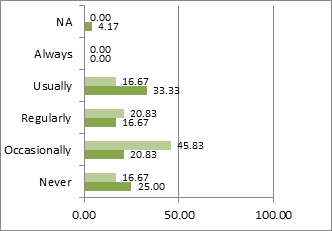

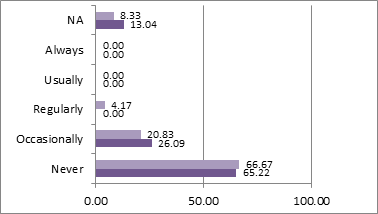

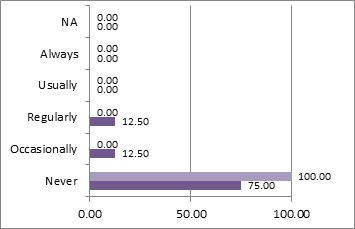

Regarding the control group, as can be seen in figure 3, there were no significant changes in the use of different working positions along the working day, except for forward position away from backrest, that showed a decrease of use. The differences found in this group are related to participants that did not answer before the intervention, and reported a certain answer afterwards.

|

Forward position |

Forward position away from backrest |

|

|

|

|

Upright position |

Reclined position |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Frequency position use reported by control group participants before and after intervention (colours lighter and darker, respectively).

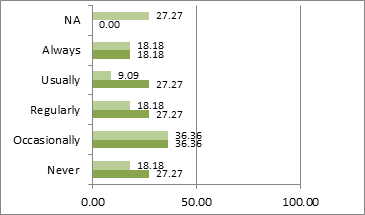

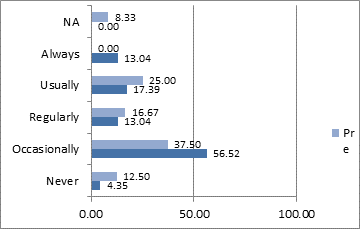

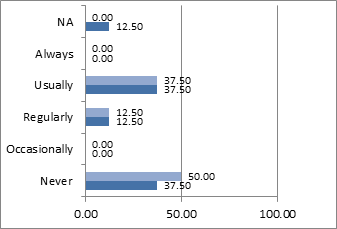

When analysing the results of each experimental groups separately, several differences were found between the changes on the groups.

Experimental group 1, which received both course and computer application, showed the greatest changes (fig. 4). Forward position showed to be less used, as "regularly" and "usually" answers decreased, and "occasionally" and "never" answers raised. Forward position away from backrest showed little changes, remaining lightly used. About upright position,, a trend to use it as a usually position was identified on results. There were found some participants that quitted using this position. Reclined position showed no changes, as it was a barely used position and remained the same.

|

Forward position |

Forward position away from backrest |

|

|

|

|

Upright position |

Reclined position |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Frequency position use reported by group 1 participants before and after intervention (colours lighter and darker, respectively).

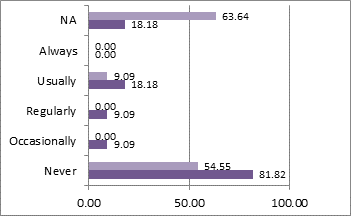

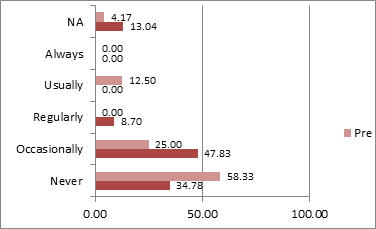

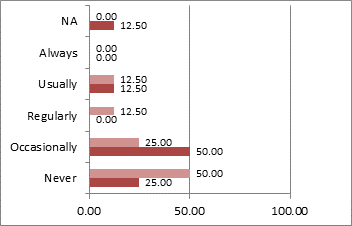

Participants in experimental group 2, which only received the course, showed different trends in changing their posture habits as group 1 participants (fig.5). Forward and upright positions were more used after intervention, but no position was clearly used as the reference or more used position. Forward position away from backrest proved to be less used as a usual posture, but increased the sporadic use. Finally, reclined position remained the same, as it was little used before and after intervention.

Experimental group 3, which only received the computer application, showed little changes, considered mostly non significant due to the sample size of this group (8 participants) (fig. 7). Changes showed trends to decrease the use on one particular position, and increased slightly the occasional use of the forward position away from backrest and reclined position.

|

Forward position |

Forward position away from backrest |

|

|

|

|

Upright position |

Reclined position |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Frequency position use reported by group 2 participants before and after intervention (colours lighter and darker, respectively).

|

Forward position |

Forward position away from backrest |

|

|

|

|

Upright position |

Reclined position |

|

|

|

Figure 6. Frequency position use reported by group 3 participants before and after intervention (colours lighter and darker, respectively).

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention to change and improve the postural habits of office workers, so to reduce the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Using different actions, the objective of this intervention was to improve the ergonomic conditions and postural habits of these workers and change their sedentary lifestyle, both at work and at rest.

Along with the effectiveness of the complete intervention, it was important to determine which of the actions taking part of the intervention was the most effective.

Results yielded that most of the workers involved in the programme showed positive changes in their working positions and postural habits. Changes showed a trend to use upright position as a reference working position, but also showed a trend to introduce variety of working postures during the day after the intervention, and to avoid the more harmful positions. As these changes were detected in the experimental groups and not in the control group, the effectiveness of the intervention was proved.

Regarding the effectiveness of the different actions taking part in the intervention, we cannot point an action categorically as the most effective, as group 3, that only received the ErgoUIB computer application, was too little sampled to be significant. In spite of this, results showed that the most positive changes in postural habits were found when applying the complete ergonomic intervention; that is, combining the postural education course with the ErgoUIB computer application use.

The results obtained in this experiment demonstrate that the complete ErgoUIB intervention was useful for improving postural habits of the office workers of the UIB. ErgoUIB facilitated the incorporation of different activities and tools into the lives of workers that might influence both their work and their lifestyle; i.e., this intervention also provides tools to improve their general health.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Universitat de les Illes Balears and the General Direction of Universities of the Balearic Government. We wish to express our most sincere thanks to the UIB workers who participated in this study.

A preliminary version of this paper was presented at ORPconference 2014.

References

1. Hedge, A., Puleio, J., & Wang, V. (2011). Evaluating the impact of an office ergonomics program. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 55(1), 594-598.

2. Janwantanakul, P., Pensri, P., Moolkay, P., & Jiamjarasrangsi, W. (2011). Development of a risk score for low back pain in office workers -a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12 3. Johnston, V., Souvlis, T., Jimmieson, N. L., & Jull, G. (2008). Associations between individual and workplace risk factors for self-reported neck pain and disability among female office workers. Applied Ergonomics, 39(2), 171-182. 4. Kietrys, D. M., Galper, J. S., & Verno, V. (2007). Effects of at-work exercises on computer operators. Work, 28(1), 67-75. 5. van den Heuvel, S. G., de Looze, M. P., Hildebrandt, V. H., & Thé, K. H. (2003). Effects of software programs stimulating regular breaks and exercises on work-related neck and upper-limb disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 29(2), 106-116. 6. Viljanen, M., Malmivaara, A., Uitti, J., Rinne, M., Palmroos, P., & Laippala, P. (2003). Effectiveness of dynamic muscle training, relaxation training, or ordinary activity for chronic neck pain: Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 327(7413), 475-477. 7. Taieb-Maimon,M., Cwikel, J., Shapira, B., Orenstein, I. (2012) The effectiveness of a training method using self-modeling webcam photos for reducing musculoskeletal risk among office workers using computers. Applied Ergonomics 43, 376-385.8. Sihawong, R., Janwantanakul, P., Sitthipornvorakul, E., & Pensri, P. (2011). Exercise therapy for office workers with nonspecific neck pain: A systematic review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 34(1), 62-71. 9. Tsauo, J. -., Lee, H. -., Hsu, J. -., Chen, C. -., & Chen, C. -. (2004). Physical exercise and health education for neck and shoulder complaints among sedentary workers. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 36(6), 253-257. 10. van Poppel, M. N. M., Hooftman, W. E., & Koes, B. W. (2004). An update of a systematic review of controlled clinical trials on the primary prevention of back pain at the workplace. Occupational Medicine, 54(5), 345-352. 11. Verhagen, A. P., Karels, C., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A., Feleus, A., Dahaghin, S., Burdorf, A., et al. (2007). Exercise proves effective in a systematic review of work-related complaints of the arm, neck, or shoulder. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(2), 110.e1-110.e14. 12. Cheung, K. M., Karppinen, J., Chan, D., Ho, D. W., Song, Y. Q., Sham, P., et al. (2009). Prevalence and pattern of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging changes in a population study of one thousand forty-three individuals. Spine, 34(9), 934-940. 13. Moreno Morales, N., Pineda Galán, C., Díaz Mohedo, E., Barón López, F., Sánchez Guerrero, E., & Labajos Manzanares, M. (2003). Estudio transversal de las algias vertebrales en los fisioterapeutas. Fisioterapia, 25(1), 23-28. 14. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. (1999). Protocolos de vigilancia sanitaria específica: Pantallas de Visualización de Datos. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Centro de Publicaciones.

Papers relacionados